Imperial Navy pilot Nobuo Fujita flew the only enemy bombing mission over the continental United States during World War II. (U.S. Navy)

Deep in the forests of southwestern Oregon is a redwood sapling — a peace offering at the site of an act of war.

Friday marks the 81st anniversary of the end of the only enemy aerial bombing campaign to strike the continental United States during World War II.

The plan was to firebomb the vast forests of America’s northwest in retaliation for the April 18, 1942, Doolittle Raid on Tokyo. The Japanese hoped their modest effort would torch millions of acres of trees and deprive the U.S. defense industry of tons of wood crucial to the war effort. The Americans would have to send thousands of troops to fight the fires.

Nobuo Fujita, a veteran Japanese Navy pilot, advocated the attack and was given the honor of taking the war to the American home front.

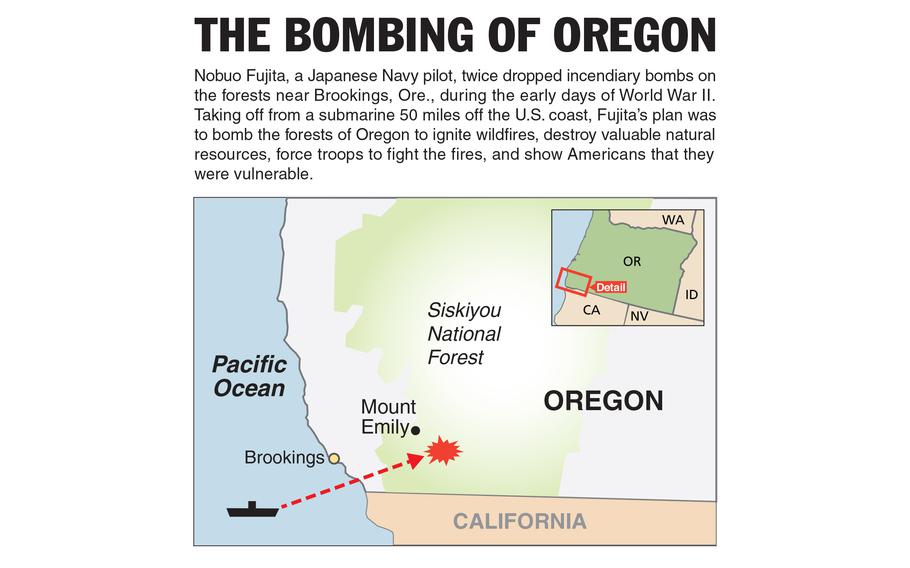

Twice he would fly his submarine-launched floatplane over the forests near Brookings, Ore., release his bombs and make his way to a rendezvous with the I-25 transport submarine waiting for him off the coast.

Though Fujita did not know it at the time, nearly all the bombs fizzled. An alert student forest ranger stomped out one small flare-up. The wet forest floors took care of the rest.

(Noga Ami-rav/Stars and Stripes)

The bombs over Brookings were the only enemy aerial attack on the lower 48 states during the war. But the lack of any real damage left it as little more than a curious footnote in a war that spread carnage across Europe and Asia.

While the mission was a failure, the pilot was remorseful for the violence he intended to inflict on the civilians living in Brookings, the timber town of about 500 people closest to his target.

As he rebuilt his life in the wreckage of postwar Japan, Fujita had one overriding desire — to return to Oregon to apologize for the attack. After all, he had come up with the idea of the attack after he had been attacked by the Americans.

Revenge for revenge

The Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii on Dec. 7, 1941, had killed 2,403 people, destroyed two battleships, damaged 17 other ships and destroyed scores of airplanes, fuel tanks and buildings.

But the attack had missed the three aircraft carriers of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, which were out to sea on maneuvers. American leaders wanted to launch a blow to put the Japanese on the defensive.

Army Air Force crews under Lt. Col. Jimmy Doolittle were sent to Pendleton, Ore., to learn how to make short takeoff runs in B-25 Mitchell bombers. The crews and planes were loaded onto the aircraft carrier USS Hornet, set out across the Pacific Ocean and launched to bomb Tokyo and other Japanese targets.

Damage was light and only 50 people on the ground were killed, but the Doolittle Raid showed the Japanese that they were vulnerable to attack even in their own capital.

One of the bombs landed in the Yosokuna shipyard, near submarine I-25. Among its crew was Fujita, a 30-year-old veteran pilot who had flown dangerous reconnaissance missions over Australia and New Zealand. He presented his superiors with a plan: Bomb the United States.

Nobuo Fujita and his Yokosuka E14Y floatplane, a type nicknamed “Glen.” (Wikimedia Commons/public domain)

The I-25 was a large “cruiser” submarine that carried a Yokosuka E14Y floatplane, a type nicknamed “Glen” by the Allies. The submarine would surface, and the crew would scramble to set up a crude launching ramp. On return, the plane was winched into the hold of the I-25, which could then submerge and sneak away.

Fujita needed a target. Much of the West Coast of the U.S. bristled with forts and Navy bases. Attacking the Navy at San Francisco or Seattle, even trying to bomb a medium-sized target along the coast would be met with anti-aircraft guns brought in after Pearl Harbor.

The Glen had a cruising speed of 90 mph, making it a sitting duck for any American coastal battery or destroyer patrol.

The American weak point was Oregon, whose sparse population and rocky coast left it relatively unprotected. No big cities. No bustling ports.

What Oregon did have was forests — Douglas firs, Ponderosa pines, Sitka spruce that were being turned into lumber to build hangars, barracks, ship decks and ammunition crates. The idea was to drop thermite firebombs that would ignite massive wildfires, destroy millions of feet of war material, force troops to be redirected to fight the fires and show the Americans that they too were vulnerable in their homes.

Bombs over Brookings

In the early hours of Sept. 9, 1942, the I-25 surfaced off the coast of Crescent City, Calif. Fujita received a final briefing.

“You are going to make history today,” Fujita recalled the submarine commander told him. “You are going to show them who really owns the Pacific.”

Catapulted into the predawn sky, carrying two 168-pound bombs. Fujita later recalled the sun rising over the mountains and the rolling emerald green forests that stretched into the distance wherever he looked. He was enchanted but not dissuaded from his mission. He dropped his bombs and turned back to sea.

As he had expected, the plane was widely seen, but there was no weapon in the area that could reach the floatplane as it traveled west to rendezvous with the submarine.

Unsure of the effect of the bombs, Fujita requested to fly another mission. Officers debated back and forth. Surely the first bombing had alerted American forces of the submarine’s area of operation.

To be safe, the submarine commander repositioned to about 50 miles off Cape Blanco and waited for night on Sept. 29 to launch Fujita and his floatplane, armed with a pair of incendiaries.

Struggling to see in the darkness of the unpopulated forest, Fujita believed he found the same point as the first attack. He dropped the bombs and turned back to sea.

Worried that his first raid might have alerted American high-altitude cannons and machine guns along the coasts, Fujita cut his engine and glided above the trees, beaches and waves until far enough out over the ocean to switch the propeller back on and find the I-25.

Upon his return, the submarine cruised away from the U.S. and signaled Tokyo that the mission had been accomplished.

“INCENDIARY BOMB DROPPED ON OREGON STATE. FIRST AIR RAID ON MAINLAND AMERICA. BIG SHOCK TO AMERICANS,” trumpeted the headline in Tokyo’s Asahi Shimbun newspaper.

The report was half correct. Due to a malfunction or the wet Oregon weather, none of the bombs, on either mission, caused much of a fire. An alert U.S. Forest Service worker, seeing smoke during the first raid, was able to put out flames from one bomb by himself. The bombs from the second attack were never found.

But the raids did provoke alarm up and down the coast.

Good luck and a guilty conscience

Fujita had fortune on his side throughout the dismal years of World War II.

Because he was assigned to the I-25 submarine plane, Fujita avoided the fate of hundreds of his pilot friends who died at the battles of the Coral Sea and Midway.

Belief that the firebombing in Oregon was a major tactical victory, Fujita was hailed as a hero in Japan and transferred off the I-25. He would train new recruits to replace the decimated ranks of veteran pilots killed in the major sea battles that Fujita has missed.

The I-25 set out to rejoin the war, with a new pilot for the floatplane. In September 1943, a year after Fujita’s attacks on Oregon, the destroyer USS Patterson sank I-25 near New Hebrides, killing all 100 crew members.

In Japan, Fujita was training some of the new recruits in a new tactic — suicidal kamikaze attacks requiring pilots to fly their planes into allied ships.

After the war, Fujita opened a hardware store and along with the Japanese recovery made a new life for himself, and for two decades never talked about the war with his family — until the day he announced to his family that they were going to Oregon to visit the townspeople he had tried to kill.

It was 1962 when Fujita received an invitation from the Brookings Jaycees to visit the town on the 20th anniversary of his mission. The town wanted him to be the Grand Marshal of the annual Azalea Festival. Japan was now an ally in the Cold War, and Tokyo would be the site of the 1964 Summer Olympics. City churches and service clubs had raised the $3,000 that it would take to bring Fujita and his family to Oregon.

Fujita accepted but was uncertain of the reception he would receive. The Japanese government contacted the State Department to receive assurances that Fujita would not be arrested as a war criminal when he arrived.

He often told of his concern that he would be taunted and have eggs thrown at him.

Former Japanese Navy pilot Nobuo Fujita visited Brookings, Ore., in 1962 and presented the city his family’s samurai sword during a meeting with the Brookings Jaycees. Fujita had flown a submarine-launched floatplane that attempted to set fire to forests in southwestern Oregon in September 1942. It was the only manned attack on the mainland United States during World War II. The sword remains on display in the Brookings Public Library. (AP)

The sword and the tree

As an act of contrition and friendship, Fujita offered the most-sincere apology that he could think of: He surrendered his family’s 400-year-old samurai sword to city officials.

His daughter, Yoriku Asakura, told The New York Times in 1997 that Fujita’s fear and guilt was deep. If he was met with anger by the citizens of Oregon, he claimed he would commit seppuku — ritual suicide — using the sword.

“He wanted to take responsibility for what he had done.” Asakura said.

Instead, most in the town treated him with kindness, making certain that he didn’t know about a full-page ad taken out in the Brookings-Harbor Pilot opposing his visit, signed by 100 residents.

‘WHY STOP WITH FUJITA? WHY NOT ASSEMBLE THE ASHES OF JUDAS ISCARIOT, THE CORPSE OF ATTILA THE HUN AND THE A SHOVEL FULL OF DIRT FROM THE SPOT WHERE HITLER DIED?” the ad read.

Reports in the local newspaper said the forest service worker who had put out the fire from the first firebombing was so angry at the idea that the town had invited Fujita to visit as a guest of honor that he was locked in jail for the short duration of the visit.

Two local teenagers displayed a Japanese flag, which older locals pulled down before the car carrying Fujita passed the spot.

Fujita did his part to try to make amends. Along with the sword, he gave $1,000 to the Brookings library to buy English-language books that would inform locals about the art and culture of Japan. He paid for a study abroad program for Brookings teenagers to come to Japan and even offered to host them in his home. He returned in 1995 for ceremonies installing his sword into a special exhibit in the new city library.

In 1997, Fujita was hospitalized with terminal lung cancer. The city of Brookings proclaimed him an honorary citizen and ambassador of international goodwill.

He died Oct. 2, 1997, at age 85.

In Tokyo is the Yasukuni temple of the Shinto religion. It is mostly black lacquered timber and white billowing screens. It is believed warriors who fought for the emperor are forever honored in the Yasukuni Shrine, a site where militarists and nationalists often rally in a show of “bushido,” the warrior code of honor.

Fujita showed his loyalty to the emperor and acted with bushido in 1942 when he twice bombed Oregon.

But at his death, his family did not believe his soul was destined for a militarist shrine.

Instead, his daughter brought some of his ashes to a spot on Mount Emily near Brookings and sprinkled them around the bombing site. A redwood sapling was planted as a sign of peace.

Instead of Yasukuni, she said her father’s soul would forever be flying over the forests of Oregon.