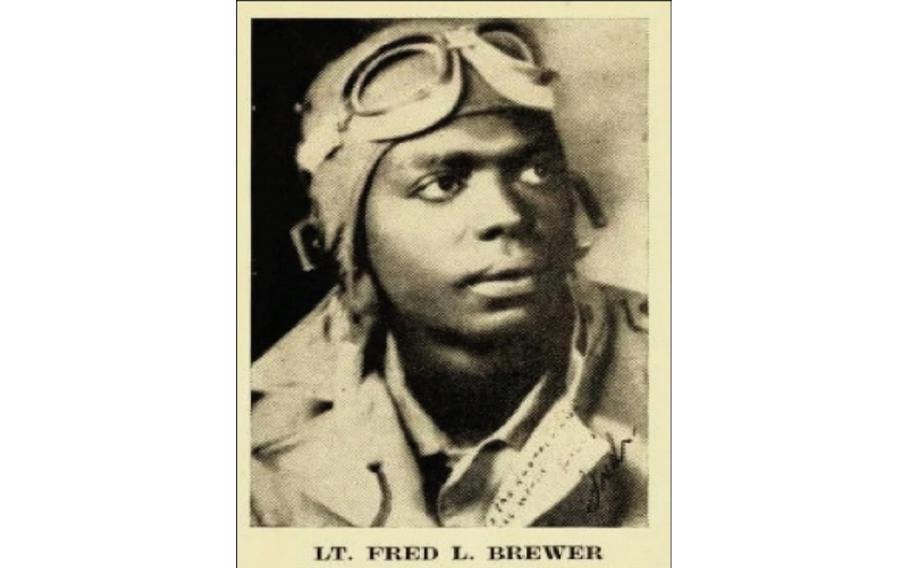

The remains of Lt. Fred L. Brewer Jr., who flew with the Tuskegee Airmen, were identified in August 2023, nearly 80 years after his final mission. (Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency)

Travelin' Lite was a good airplane. On scores of missions, the P-51 fighter with a skinny rabbit painted on its nose had brought its pilots home. Now, at an American air base in Italy, the Lite One, as the plane was called, was about to carry another aviator into action.

Shortly before 9: 30 a.m. on Sunday, Oct. 29, 1944, Lt. Fred L. Brewer Jr., 23, one of the renowned World War II African American pilots known as the Tuskegee Airmen, climbed into the cockpit for a mission to escort bombers attacking Regensburg, Germany.

A member of the ground crew strapped him in, closed the canopy and rode on the wing as the plane taxied to the runway. Brewer gave him the okay sign with his hand. The ground man hopped down, and Brewer took off. He was never seen again.

Last month, the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) said it had concluded that previously unidentified remains recovered from northern Italy after the war were those of Brewer.

He is only the second Tuskegee Airman missing from World War II to be accounted for. The first, Capt. Lawrence E. Dickson of New York, whose P-51 went down in Austria, also in 1944, was officially identified in 2018.

Twenty five still are missing, the DPAA says. The agency, which is based in Arlington, Va., seeks to account for service members missing in action from the country's wars beginning with World War II.

The identity of Brewer's remains was established via, among other means, recent historical research and a DNA link to a paternal cousin, the DPAA said.

Brewer, of Charlotte, was among the more than 900 Black pilots who were trained at the segregated Tuskegee Army Air Field in Alabama during the war.

They were African American men from all over the country who fought racism and oppression at home and enemy pilots, bad weather and antiaircraft gunners overseas.

The remains of Lt. Fred L. Brewer Jr., who flew with the Tuskegee Airmen, were identified in August 2023, nearly 80 years after his final mission. (Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency)

More than 400 served in combat, flying patrol and strafing missions, and escorting bombers from bases in North Africa and Italy. The tail sections of their fighter planes were painted a distinctive red.

Brewer, the son of a hotel bellman, had graduated from Shaw University in Raleigh, N.C., where he had reportedly received an award from a prominent Black fraternity.

His 1942 draft registration card said he stood just under six feet tall and weighed 136 pounds.

He had a younger sister named Gladys, who was a teacher at the local segregated Second Ward High School. The family lived in Charlotte's Brooklyn section, a largely Black neighborhood that was razed in the 1960s.

"I remember how devastating it was when they notified my family, my aunt and uncle, that he was missing," said Robena Brewer Harrison, 84, of New York, a cousin. "It just left a void within our family. My aunt, who was his mother, Janie, she never, ever recovered from that."

She said Brewer's mother had a stroke afterward, and was in a wheelchair. She died five years later at the age of 49, according to her death certificate.

"She died of a broken heart," said Brenda L. Brewer, 74, of Charlotte, another cousin. "If there can be any healing in death, I hope she's healing now."

"He's coming back now, and I'm happy for him, and I finally finish a mission of mine in life, to bring this pilot home," she said.

Although she never knew the lieutenant, she said in a telephone interview that she had heard his story when she was growing up and had resolved to somehow help get him home. She said funeral arrangements have not been made but she would like to see the remains buried in Charlotte.

Brewer's plane went down about 11:15 a.m. on Oct. 29, 1944. He and 56 other fighters had been headed on a 1,000-mile round trip mission from the American base at Ramitelli, Italy, over the Alps, to Regensburg.

But there were overcast skies. The fighters had trouble finding the B-24 bombers they were to escort.

About 340 miles into the trip, as the P-51s were climbing through cloud cover above Dellach, Austria, a fellow pilot, Lt. Charles H. Duke, saw Brewer pull up too sharply and "stall out."

"I immediately lost sight of him in clouds," Duke reported later, according to government records.

Brewer's plane crashed. But it did not come down in Dellach. It crashed about 20 miles to the south, in Moggio Udinese, just across the border in Italy, a fact that would later complicate the search for the identity of his remains.

The plane Brewer flew that day had mostly been flown by another Tuskegee pilot, 1st Lt. John F. Briggs, according to Craig Huntly, a California-based Tuskegee historian.

Huntly said in a recent telephone interview that long after the war he had befriended the plane's ground crew chief, James C. Atchison, who told him the story of Travelin' Lite.

The nose of the P-51 bore the name of the plane and a drawing of a thin rabbit holding a toothbrush. "And that's just how light the bunny was traveling," Huntly said. With "nothing but a toothbrush."

The plane may have been named for the 1942 song "Trav'lin' Light" by the jazz singer Billie Holiday, he said.

Briggs had flown 70 missions in the plane and was about to return to the United States, Huntly said.

Brewer had flown it a few times. The two pilots discussed renaming it, but Brewer wanted to keep the name, because it had safely brought him home, too, Huntly related.

Huntly recalled how Atchison had described that day. "I strapped him in, buttoned up the canopy, rode his wing from the revetment out to the runway. We looked at each other. He gave me the okay sign with his fingers. I hopped off the wing and that was the last that I saw of" him.

Brewer's single-engine plane fell about 19,000 feet. It crashed and burned in a remote area. No one lived nearby and there were no known eyewitnesses.

His body was removed from the wreckage by local Italian officials and buried in a civilian cemetery, according to military records.

In 1946 his body was moved to an American cemetery in Mirandola, Italy, about 150 miles away, the records say. A wooden grave marker was erected.

Two years later the skeletal remains - then identified only as X-125 - were disinterred and a few months after that were moved to an American cemetery in Florence, Italy, where they arrived on March 11, 1949.

Nine months later, back in Charlotte, Brewer's mother died.

In 2011, as the DPAA was reexamining cases of World War II airmen missing in action in Europe, an agency research analyst, Josh Frank, began studying crash sites in Italy.

"I started to go over every plane that crashed in Italy and kind of put it into a database," he said in a recent telephone interview. "Lt. Brewer's case was not on my radar . . . because his recorded loss location . . . was in Austria."

But Frank started checking other reports and stumbled on a website hosted by some volunteer Italian archaeologists. The website reported that a resident of Moggio Udinese had reportedly used what appeared to be pieces of an airplane to erect a large metal crucifix there to honor fallen pilots.

"That was kind of my first hint that something had happened in Moggio Udinese," Frank said. "What was it?"

Research revealed that a P-51 had crashed there about 11:15 a.m. on Oct. 29, 1944, and the body of an unidentified pilot had been recovered, he said.

Scouring reports of American plane losses across Europe that day, Frank found that only one single-engine aircraft had gone down at that time on that date: Brewer's P-51.

So there was a good chance that the pilot recovered from the wreckage at Moggio Udinese was Brewer.

But the DPAA needed a DNA sample from Brewer's paternal family line before the remains could be examined. "It took a while," Frank said.

Eventually, DNA was obtained from a paternal cousin. On June 21, 2022, the remains of X-125 were disinterred from the Florence American Cemetery and taken to the DPAA Laboratory at Offutt Air Force Base in Nebraska for analysis.

DNA obtained from the left thigh bone matched the DNA from Brewer's male cousin.

On Aug. 10, the DPAA reported: "The laboratory analysis and totality of circumstantial evidence available establish the remains as those of Second Lieutenant Fred L. Brewer Jr.. . .U.S. Army Air Forces."

"It is bittersweet," said his cousin, Robena Brewer Harrison. "A long time coming. Did I ever think that I or Brenda . . . would ever actually witness this day? [It] is beyond human comprehension."