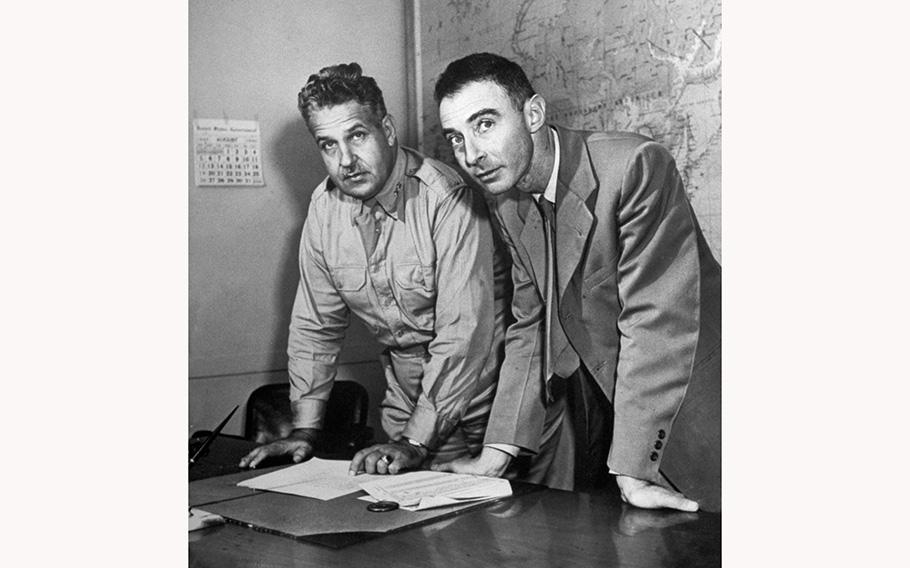

Army Gen. Leslie R. Groves, military head of the Manhattan Project, stands beside Professor Robert Oppenheimer in 1942. (U.S. government)

(Tribune News Service) — In the late spring of 1952, Sen. Brien McMahon, a presidential contender, and his right-hand staffer William Borden hired a former FBI agent to investigate whether Oppenheimer, father of the atomic bomb, was a Communist spy. Oppenheimer, the nuclear physicist who headed the Los Alamos Laboratory, was a leader in organizing the Manhattan Project, which created the first nuclear weapons.

According to historian Patricia McMillan's account in "The Ruin of J. Robert Oppenheimer," the FBI agent would eventually end the investigation trying to convince Borden that Oppenheimer was a Communist spy.

McMahon died before the investigation concluded, the election held, and Oppenheimer's later removal. He would die of cancer in July of 1952 at age 48 at Georgetown University Hospital. From his deathbed he telephoned the Democratic state convention in Hartford that if elected president, he would direct the Atomic Energy Commission to build hydrogen bombs by the thousands.

Seizing the atomic issue

McMahon was an ambitious senator from Norwalk who was first elected in 1944. In 1945 when word of atomic weapons reached the public, McMahon was quick to jump on them politically. He served as the chairman of the Senate's Special Committee on Atomic Energy.

In 1946, during the intense debate over McMahon's proposed Atomic Energy Act, he was among the first to suggest atomic tests be carried out on naval ships, a suggestion that was realized on Bikini Atoll. During the debates McMahon's atomic bill bore his name, the McMahon Act.

McMahon maneuvered himself into the center of the first atomic political debate — whether atomic weapons and research should be under civilian control.

"You had the military leadership of the Manhattan Project very much in favor of retaining the wartime style of control," said James Stemm, curator of the National Museum of Nuclear Science & History. "And you have people like Oppenheimer ... who wanted to see civilian control brought back into it."

It was a frantic time. President Harry S. Truman wanted legislation passed quickly to formalize what would become of The Manhattan Project and its sprawling complex of research labs, factories, and facilities. Whole cities in Washington and Tennessee were built in service of the project. Tens of thousands of people lived and worked during World War II in secret.

The initial Atomic Energy Act legislation was held up in the senate after drawing a tidal wave of criticism from many scientists including noted physicist, Manhattan Project scientist and nuclear arms race critic Leo Salazard. They feared that the secrecy provisions and structure of the initial bill would leave nuclear weapons and research in military hands.

"What McMahon does in this period is basically seize control of this issue," said nuclear historian Alex Wellerstein, a professor at the Stevens Institute of Technology in New Jersey. Wellerstein has extensively studied the development of the nuclear security state. "He sees this opportunity to have this defining issue, and he ends up giving scientists opposed to the military a big voice."

Becoming a hawk

During the drafting of the Atomic Energy Act a spy scandal called the Gouzenko Affair occurred in Canada, which prompted McMahon to add much higher provisions of military secrecy to his bill. The final bill tries to merge peaceful atomic research while also maintaining strict military secrecy.

.jpg/alternates/LANDSCAPE_910/Brien_McMahon_cropped.jpg)

Then-Sen. Brien McMahon, D-Conn., as seen in 1945. (WikiMedia Commons)

"McMahon justified this after saying that by putting things in the (legislation) that were deliberately opposite that would force everybody using the law to figure out the rational, enlightened solution," said Wellerstein. "But what immediately becomes clear is that the lofty aspects of the law, nobody is empowered to actually use them."

Shortly after the passage of his bill McMahon's committee was embroiled in the debate over whether to push for the development of hydrogen bombs, which are much more powerful than a typical nuclear weapon.

At this time McMahon encountered the 28-year-old William Borden, who had written a book about future wars with nuclear weapons. Borden also wrote a letter called "the inflammatory document" that McMahon read in which Borden called for Truman to issue Soviet Chairman Joseph Stalin a nuclear ultimatum.

"Present the issue directly to Stalin — atomic peace or atomic war," wrote Borden. McMahon hired him to a high-ranking staff position for his congressional committee. A young nuclear hawk was now working to push nuclear policy.

Oppenheimer, leading a secret scientific advisory committee, opposed developing hydrogen bombs on technical and moral grounds. At the time he was also pushing for open, international control of nuclear technology through the United Nations.

"The United States was not interested. The Soviet Union was not interested," said Stemm. "The idea was basically dead on arrival."

At the same time America was growing more and more paranoid about nuclear weapons. A series of spy scandals over the ensuing years revealed that the Manhattan Project had been infiltrated by Soviet spies. Nuclear secrets had passed to the Soviet atomic bomb project.

By 1949, the Soviet Union would test their first atomic bomb. This threw gasoline on the fiery debate over whether to develop hydrogen bombs. Wellerstein explained that McMahon thought that nuclear war was going to happen and that the U.S. had to have atomic supremacy.

"He says that if the Soviet Union gets the H-Bomb they have a gun pointed at our hearts," Wellerstein said of McMahon. "He can't live with that sense of vulnerability ... mutually assured destruction means mutual vulnerability."

In now declassified congressional transcripts McMahon downplays Oppenheimer and his committee's worries about nuclear fallout, nuclear contamination and triggering an arms race. Those worries would eventually be borne out by the historical record.

McMahon was "incredulous," said Wellerstein. "He cannot believe the scientists actually believe this."

In the transcripts McMahon cites contrary opinions by one of the fathers of the hydrogen bomb, Edward Teller.

McMahon and Oppenheimer

Eventually Truman decided to pursue building hydrogen bombs. But this was not enough to satisfy the people angered by Oppenheimer's resistance. Those who opposed the hydrogen bomb were seen as deliberately stalling its development. Borden would push McMahon to tell Truman to have Oppenheimer removed up until McMahon's death, all while advocating nuclear armament.

"The winners are the ones who become the most bitter about it," said Wellerstein. "They really believe that these people gummed up the works. In their view they need to be punished."

Teller would be the sole scientist to testify against Oppenheimer during the security clearance hearing that marked the end of Oppenheimer's relationship with the U.S. government. Borden, too, would play a role in the proceedings testifying against Oppenheimer and "pass out of history," according to Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Richard Rhodes, who wrote in his book "Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb."

Whether McMahon would have actually pushed Oppenheimer out of the government remains unknown.

"It's a contentious question of whether Borden was operating on his own authority," said Wellerstein. "How much did McMahon agree with him?"

It's not clear how McMahon would have reacted to other developments in the hydrogen bomb saga. He died before the Castle Bravo detonation in 1954 that contaminated several of the Marshall Islands and sickened Japanese fisherman working roughly 80 miles away. He never knew that scientists weren't bluffing when they testified to his committee that hydrogen bombs had "unlimited destructive power."

"Who knows what he would have done," said Wellerstein. "There's a Cold War approach that you judge a man by his association. Who is he within this period? But would he have softened? I can't say."

None of this history is in the film Oppenheimer. The sprawling, three-hour movie cuts most of this period out. Wellerstein, who saw a pre-screening with scientists and academics, said that it focused on the Manhattan Project and the period just after the Soviets got the bomb. U.S. Congress is barely mentioned.

Borden, however, does make an appearance, cast as "the oiliest man," said Wellerstein. Instead of working for McMahon, Borden is depicted working for Lewis Strauss, arch-secret keeper of the Manhattan Project and another enemy of Oppenheimer's.

(c)2023 Journal Inquirer, Manchester, Conn.

Visit Journal Inquirer

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.