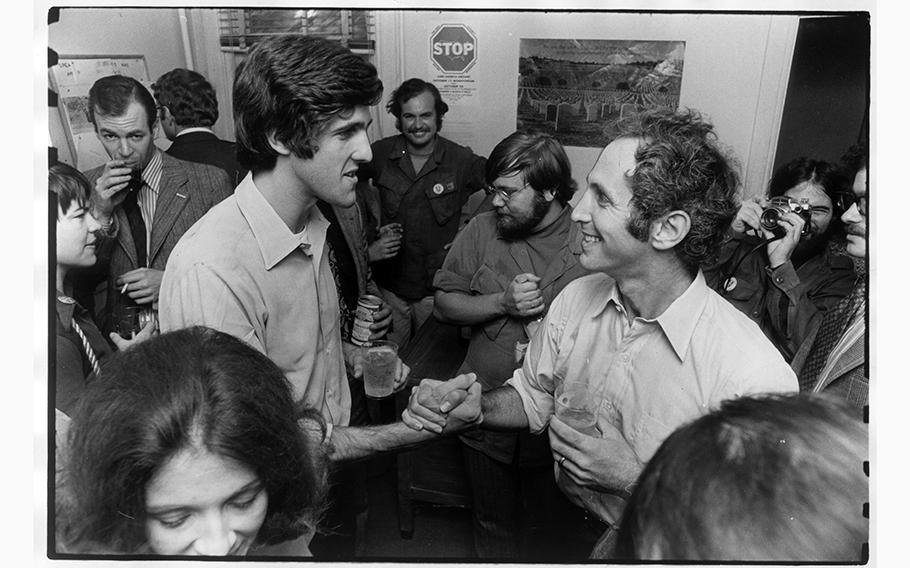

Daniel Ellsberg, right, shakes hands with the future senator and secretary of state John F. Kerry, then the head of Vietnam Veterans Against the War, in 1971. (The Washington Post)

On Nov. 6, 1969, Daniel Ellsberg walked into Sen. William Fulbright's Capitol Hill office, carrying two briefcases full of top-secret documents.

Inside the dim room, lit by lamps even in afternoon, Ellsberg sat down on a sofa near Fulbright, chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, and his aides. Ellsberg told them he wanted Congress and the public to see the documents he had brought with him. They were part of a classified defense study, a ruinous 47-volume history of U.S. involvement in Vietnam.

"This history showed a pattern," Ellsberg, who died last week at 92, recalled explaining to Fulbright in his memoir, "of the same sort of deception, the same secret threats and plans to escalate, the same pessimistic internal estimates, and the same public reassurances, over four previous presidents."

Today, Ellsberg is known for leaking the classified Pentagon Papers to the New York Times, The Washington Post and other newspapers in 1971, a radical maneuver that changed Americans' understanding of the Vietnam War. But, before going to the press, the maverick defense analyst had spent a year and a half quietly leaking the papers to leading antiwar senators and representatives - in hopes they would publicize them, hold hearings and insert them into the Congressional Record.

The politicians all declined.

Ellsberg, once a committed Cold Warrior, had spent 1965 to 1967 in South Vietnam as a State Department employee. His in-person observations of the state of the war convinced him that the U.S. and South Vietnamese militaries could not defeat the communist Viet Cong guerrillas. Back home, as an analyst for the Rand Corp., a think tank, Ellsberg worked on a secret study commissioned by then-Defense Secretary Robert McNamara on U.S. decision-making in Vietnam since World War II.

Ellsberg and his co-workers, reviewing classified material, identified disturbing trends. Presidents from Harry S. Truman through Lyndon B. Johnson had escalated U.S. involvement in South Vietnam to prop up an anti-communist regime that had little public support. American officials had regularly misled the public, predicting victory despite private warnings that the war was stalemated or unwinnable.

Ellsberg's crisis of conscience reached its peak on Oct. 1, 1969, when he began sneaking parts of the top-secret study out of Rand Corp.'s California office and photocopying them at an acquaintance's office. His goal was to turn public opinion further against the war.

"I certainly wouldn't have courted trial or a life behind bars just to set straight the historical record of Vietnam," Ellsberg wrote in his memoir. "My interest was in stopping the ongoing killing."

Ellsberg started with Fulbright, an early supporter of the war who had turned critical of it by 1966, grilling aides to President Johnson about the war in nationally televised hearings. Ellsberg asked Fulbright whether he wanted to see the study's volume on the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin incident that had led Congress to authorize the war's escalation.

"Indeed I would!" Fulbright replied, according to Ellsberg's memoir.

"He had a smile on his face as broad as his southern drawl," Ellsberg wrote. "He reached out for the papers I was holding and took them in front of everyone. He said he would read those right away."

Over the next few months, as Ellsberg secretly copied more of the Pentagon Papers, he sent Fulbright volume after volume. Ellsberg hoped Fulbright's committee could reveal the papers during hearings and then subpoena witnesses to expose officials' deceptions further. He asked Fulbright to try to use the documents without revealing him as a source or calling him to testify about them.

Fulbright agreed. He appealed to Defense Secretary Melvin Laird to release a copy of the study, without success. Ellsberg testified before Fulbright's committee in May 1970 but did not reveal that he had the papers nor their contents.

Neither Fulbright nor Ellsberg was willing to take the lead in publicizing the classified documents. When Ellsberg met with the senator again - in December 1970, according to Ellsberg's memoir - Fulbright said he doubted that the study, which covered the war until 1968, would increase congressional opposition to President Richard M. Nixon's plan to continue the war. "Isn't it, after all, only history?" Fulbright asked Ellsberg. An aide also suggested that releasing the papers could compromise the Senate's access to other classified documents, Ellsberg recalled in his memoir.

So Ellsberg approached other antiwar lawmakers. He leaked parts of the Pentagon Papers to Sens. Gaylord Nelson and Charles Mathias and to Rep. Pete McCloskey. He had the highest hopes for George McGovern, the impassioned antiwar senator who was already planning to challenge Nixon for the presidency in 1972. But the two men's accounts of their meeting differ.

As Ellsberg told it, McGovern talked with him for hours and said he wanted to present the Pentagon Papers publicly during a Senate filibuster. McGovern pulled a copy of the Constitution off a shelf to read its speech and debate clause, which says lawmakers "shall not be questioned" for what they say in congressional proceedings. But he needed some time to think about it. A week later, McGovern called Ellsberg to say he'd changed his mind.

That's not how McGovern told it. According to the senator's account, he met with Ellsberg only for a few minutes, telling Ellsberg that the risk of acting illegally to reveal the facts was on him. "I wasn't about to break the law as a United States senator," McGovern told the writer Tom Wells for his book "Wild Man: The Life and Times of Daniel Ellsberg."

Ellsberg's memoir says that on March 2, 1971, hours after he last spoke with McGovern, Ellsberg met with New York Times reporter Neil Sheehan and told him he had a copy of the Pentagon Papers. That revelation began a series of tense, volatile interactions between the two men that ended with Sheehan taking a complete set of Ellsberg's papers to his editors.

The Times began publishing articles about the Pentagon Papers on June 13, 1971. Enraged at the breach of official secrecy, Nixon had the U.S. Justice Department obtain a court injunction barring further publication. Ellsberg then gave Ben Bagdikian of The Washington Post some of the papers, and The Post published stories about them starting on June 18, and it too received an injunction.

In the end, Ellsberg succeeded at getting one senator to release some of the Pentagon Papers: Sen. Mike Gravel of Alaska. On June 24, according to Ellsberg and Gravel, Bagdikian acted as a go-between, transferring the papers from his car to Gravel's outside the Mayflower Hotel in Washington.

On June 28, Ellsberg turned himself in to face Espionage Act charges. Late June 29, Gravel spent three hours reading parts of the papers into the record in his Senate subcommittee. At one point, while speaking of the war dead, Gravel broke down crying. His staff released copies of the documents to the press, and the next day, in a historic decision defending press freedom, the U.S. Supreme Court lifted the injunctions.

Ellsberg's leak didn't stop the war, but it did stop Nixon, in a way Ellsberg never could have expected. Determined to punish the leaks, Nixon told his chief of staff, H.R. Haldeman, to ruin Ellsberg publicly. What we know as the Watergate scandal really began when Nixon's "plumbers" burglarized the office of Ellsberg's psychiatrist in September 1971.

Their failed, illegal effort eventually contributed to a judge's decision to dismiss Ellsberg's charges. Many of the same men carried out the Watergate burglary nine months later - setting in motion Nixon's downfall.