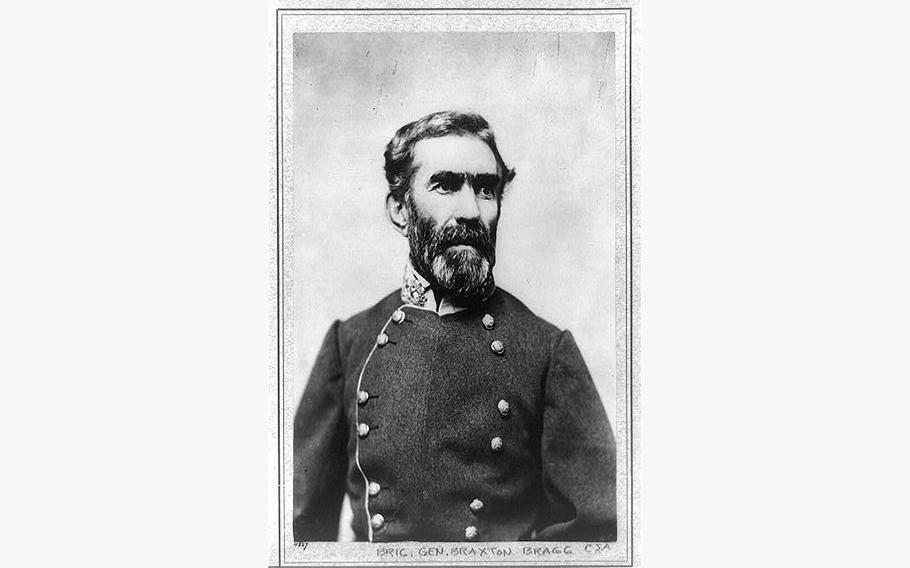

Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg. (Library of Congress)

The enslaving Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg suddenly has become a Republican primary rallying cry, after Fort Bragg in North Carolina was renamed to Fort Liberty earlier this month.

"We will end the political correctness in the hallways of the Pentagon, and North Carolina will once again be home to Fort Bragg," former vice president Mike Pence told a state GOP convention.

"It's an iconic name and iconic base, and we're not going to let political correctness run amok in North Carolina," vowed Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis.

Fort Bragg does have a venerable military history, of course. But its eponym, Gen. Bragg, not so much.

Bragg was a "merciless tyrant" who had an "uncanny ability to turn minor wins and losses into strategic defeat," wrote Sam Watkins, who served under the man historians call the South's worst and most hated general.

Bragg, a U.S. Military Academy graduate from North Carolina, first gained fame in the Mexican-American War when artillery troops fired projectiles called "grapeshots," canvas bags filled with gunpowder and metal balls packed tightly like clusters of grapes. During the 1847 Battle of Buena Vista, Gen. Zachary Taylor rode his horse over to Bragg and supposedly said, "Give them a little more grape, Captain Bragg." The phrase, a variation of the actual order, became so famous that Taylor used it in his successful 1848 presidential campaign.

But as a company commander, Bragg became known for his ruthless style that didn't exactly endear him to his troops, such as the time he ordered a soldier to ride into enemy fire to retrieve harnesses on dead artillery horses. One soldier tried to kill Bragg, slipping a 12-pound artillery shell under Bragg's cot; the shell exploded, destroying the cot, but Bragg was uninjured.

When the Civil War broke out, Confederate President Jefferson Davis called on Bragg to leave his Louisiana sugar plantation and 105 people he enslaved to be a rebel officer. In his first campaign as a full general, in 1862, Bragg brashly invaded Kentucky, figuring he would be welcomed with open arms. He issued a proclamation: "Kentuckians! I have entered your State with the Confederate Army of the West and offer you an opportunity to free yourselves from the tyranny of a despotic ruler" - meaning President Abraham Lincoln.

Bragg's "insufferable piece of nonsense," the Louisville Courier responded, "reminds us very much of the song, 'Will you walk into my parlor, said the spider to the fly.'" Most Kentuckians didn't rally to Bragg's call, and he retreated by year's end.

The day after Christmas, Bragg directed a firing squad to execute a 19-year-old infantryman, Asa Lewis, who had been convicted of desertion after going to the Kentucky home of his widowed mother without permission. When Confederate Gen. John Breckinridge of Kentucky appealed for mercy, Bragg sneered: "You Kentuckians are too independent for the good of the army. I'll shoot every one of them if I have to." Lewis's execution proceeded.

Bragg led his troops the next year into Tennessee, where he suffered a string of losses, leaving Union troops in control of Middle Tennessee. In September, he finally scored a win at the bloody Battle of Chickamauga, in northern Georgia, but fellow officers, including Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest, berated him for not pursuing the Union troops to stop them from retreating to nearby Chattanooga, Tenn.

After a personal clash with Bragg, Forrest burst into Bragg's tent and shouted, "You have played the part of a damned scoundrel, and are a coward, and if you were any part of a man, I would slap your jaws . . . If you ever again try to interfere with me or cross my path, it will be at the peril of your life," according to John Wyeth's 1899 biography of Forrest.

Bragg's subordinate officers were so upset with the general's decisions that 12 of them signed and sent a secret petition to Davis urging him to replace Bragg. Davis traveled to the battle site to talk to Bragg but decided to keep him.

Bragg's failure to destroy the fleeing Union army, though, came back to bite him. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant took command of the Union forces, which in late November proceeded to trounce Bragg's in the Chattanooga campaign.

Following his humiliating defeat, Bragg offered his resignation to Davis, who accepted it and made the general a military adviser in Richmond. After the war, Bragg worked as a civil engineer in Alabama and Texas, but he left both positions after getting into arguments with his bosses. He died in 1876, at age 59.

The general faded into history thereafter until World War I, when Major Gen. William J. Snow, the Army's chief of field artillery, began looking for locations to build two new artillery training camps. He settled on one area in Kentucky and another in North Carolina, near Fayetteville.

Snow also was in charge of Camp Zachary Taylor in Kentucky. "The name was so long, and it irritated me to take so much time in frequently writing or speaking about it," the general wrote in his 1941 memoir. So he decided to name the two new camps after past artillery officers with short names.

He named the Kentucky camp, now Fort Knox, after Henry Knox, chief artillery officer in the American Revolutionary War and the first U.S. war secretary. He named the other camp after Bragg, as a North Carolina native.

Bragg's biographers refer to his racism, with Earl J. Hess noting that Bragg opposed drafting enslaved people into the Confederate army because "he did not believe they could be made into reliable soldiers." Such a view might have been no problem to Snow, who in his own book said he refused to accept Black draftees into artillery units because "I could not make field artillerymen of them."

Camp Bragg opened in 1918 and was upgraded to Fort Bragg in 1922. The post was one of nine Southern army bases named after Confederate leaders being renamed after the 2020 killing of George Floyd. The other bases are being named after individual heroes and heroines, but the Fort Bragg naming committee pressed for the name Liberty as symbolizing the post's mission.

That's a far cry from the image of the fort's original namesake. "Bragg," Confederate officer William Dudley Hale wrote in a letter after the war, "was obstinate but without firmness, ruthless without enterprise, crafty yet without stratagem, suspicious, envious, jealous, vain, a bantam in success and a dunghill in disaster."