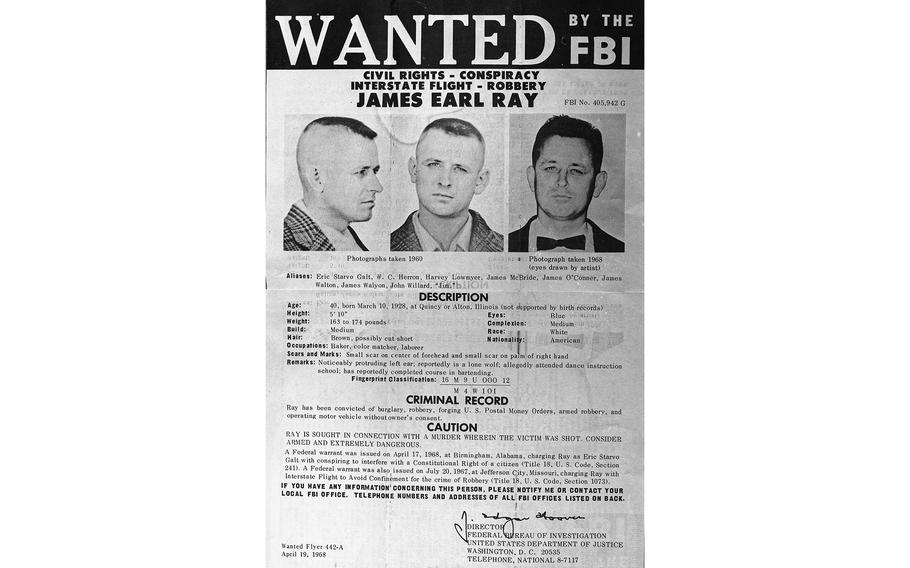

A wanted poster shows fugitive James Earl Ray. (FBI)

(Tribune News Service) — James Earl Ray drove from Los Angeles on March 18, 1968 in the 1966 white Ford Mustang he purchased in Birmingham months earlier, leaving behind a television set on which he had admiringly watched George Wallace speak.

The journey east toward Atlanta was the most recent on his cross-continent journey, which began with his escape from a Missouri prison in April 1967 and continued with him taking his Mustang with Alabama plates to Puerto Vallarta. He went to Chicago, Montreal and volunteered with Wallace’s presidential campaign in California.

That same Mustang would soon carry Ray to Selma where he expected Martin Luther King Jr. to speak.

After leaving Los Angeles, Ray drove the Mustang toward Atlanta, stopping in New Orleans and Selma, then going back to Birmingham. Ray had stayed briefly in the Magic City after his escape from the Missouri prison that caged him for seven years for robbing a grocery store.

It was while back in Birmingham that Ray purchased the rifle he used to end King’s life on the balcony of a Memphis motel 17 days after he left L.A.

While in California, living under the name Eric Starvo Galt, Ray aided former Gov. Wallace’s run for president, which brought many of his supporters from Alabama to the California campaign trail, author Hampton Sides wrote in “Hellhound on his Trail: The Electrifying Account of the Largest Manhunt in American History.”

“To the core of his angry soul, Eric Galt identified with Wallace’s rants against big government, his championing of the working man, his jeremiads on the spread of Communism,” Sides wrote. “What Galt found most appealing about Wallace, though, was the governors stance as an unapologetic segregationist. Wallace’s rhetoric powerfully articulated Galt’s own smoldering prejudices.”

As much as he admired Wallace. Ray loathed King. It was no coincidence Ray was bound for Atlanta, where King lived and preached.

“Ray’s probable stalking of Dr. King continued with his trip to Selma, Alabama following his departure from Los Angeles,” according to records in the National Archive of a Congressional committee hearing on the assassination.

“Dr. King was in the Selma area on March 21. Ray admitted being in Selma on March 22 (a motel registration card for his Galt alias confirms his stay there), but his explanation for being there was not convincing. He claimed that while driving from New Orleans to Birmingham .... he got lost and had to spend the night in Selma. The committee noted, however, that in 1968 there were two direct routes from New Orleans to Birmingham, and that Selma was on neither of them. It was situated in between the two routes, about 45 miles out of the way. The committee further determined that it would be difficult for Ray to have become lost between New Orleans and Birmingham.”

Sides notes Ray saw news of King traveling to Selma but doubts he would try to kill MLK when he was only armed with a .38 handgun and not a rifle.

For that, Ray would travel to Birmingham.

The last known address of Ray, under the name of Eric S. Galt, was at 2608 Highland Avenue in Birmingham.

“The house has since been demolished, and a convenience store occupies the location today,” journalist Stan Diel wrote for AL.com in 2010.

Ray first tried Long-Lewis hardware in Bessemer on March 29, 1968, Sides wrote, but did not think the guns there were powerful enough. He went from there to Aeromarine Supply Company, where he bought a Remington Gamemaster .243. He returned the rifle the next day for the more powerful .30-06 Remington Gamemaster 760.

“The store where he bought the gun was on property that now is part of Shuttlesworth International Airport, according to the book. The airport was named after civil rights icon the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth in 2008,” the 2010 article stated.

“When Ray bought the rifle, he identified himself as Harvey Lowmeyer and listed an address in the 1900 block of 11th Street South as his home.”

“The biggest mystery from Ray’s time in Birmingham is why he was here at all,” Sides said in a 2010 AL.com interview. “The only explanation found so far is his affinity for Wallace.”

“He could have bought the gun at a gun store in Georgia. But he chose to go to Birmingham to buy the gun,” Sides said. “I don’t know why.”

Having stalked King’s movements in Atlanta, Ray decided to travel to Memphis where King was leading a protest by the city’s sanitation workers.

Signing in at the New Rebel Motel, Ray listed his name and address as “Eric S. Galt, 2608 Highland Avenue, Birmingham, Alabama,” Sides wrote.

Ray would soon relocate to a nearby rooming house with a better view of King’s motel.

As storms battered the Mason Temple, King gave what turned out to be one of his most remembered speeches. It was his last.

“We aren’t going to let any mace stop us. We are masters in our nonviolent movement in disarming police forces; they don’t know what to do. I’ve seen them so often,” King said.

“I remember in Birmingham, Alabama, when we were in that majestic struggle there, we would move out of the 16th Street Baptist Church day after day; by the hundreds we would move out. And Bull Connor would tell them to send the dogs forth, and they did come; but we just went before the dogs singing, “Ain’t gonna let nobody turn me around....

“And we just went on before the dogs and we would look at them; and we’d go on before the water hoses and we would look at it, and we’d just go on singing “Over my head I see freedom in the air.” And then we would be thrown in the paddy wagons, and sometimes we were stacked in there like sardines in a can. And they would throw us in, and old Bull would say, “Take ‘em off,” and they did; and we would just go in the paddy wagon singing, “We Shall Overcome.”

The next day, from the rear of a rooming house, Ray stood in a bathtub to fire the shot.

The tragic deed done, Ray scooped up his belongings from the seedy flophouse and ran to the Birmingham-bought Mustang he had driven across America. He ditched his belongings, including the rifle he bought in Alabama, in the doorway of a nearby business.

“After the assassination Ray drove through Alabama, but didn’t stay, as he had initially planned. Instead, he ditched camera equipment somewhere east of Florence, and drove on to Atlanta,” Diel wrote in 2010.

Ray, historians have speculated, may have thought Wallace would pardon him for killing King — assuming Wallace won the 1968 presidential election.

“He harbored a vague hope that George Wallace’s Alabama ... would protect him, that the majority of citizens would praise him for his act and shield him from pursuers,” Sides wrote. “It was a pitifully naive train of reasoning.”

Ray was charged in federal court in Birmingham on April 17, 1968, for shooting King and soon led authorities on a global manhunt.

The Mustang he purchased here was found in Atlanta, still with its Alabama plates.

On June 8, 1968, Ray was arrested at London’s Heathrow Airport.

Former Birmingham Mayor Arthur Hanes represented Ray with his son, Art Hanes Jr., before a new legal team took over.

Hanes Sr. was a staunch segregationist, compared to his replacement as mayor, Albert Boutwell.

The younger Hanes discussed the Ray case with AL.com in 2013:

“Hanes Jr. says Ray was “browbeat” by his new lawyer into making a confession.

“To this day, Hanes Jr. continues to say he believes Ray didn’t fire the shot that killed King. What would have been Exhibit A of Hanes Jr.’s defense hangs on his office wall, an aerial photograph of the Lorraine Motel and its surroundings in Memphis.

“Ray wrote a book claiming a conspiracy and government cover-up. The King family joined Ray’s relatives in 1997 in calling for a trial to discover the full truth about what happened in Memphis.

“For years, Hanes Jr. has said there was interesting information Ray provided him. Hanes Jr. still isn’t saying what that may be.

“It’s important in the sense that it accounts for what he was doing that day,” Hanes Jr. says. “It’s the explanation of how did your gun get there, how did this happen. It’s just an interesting link to the puzzle. I’ll share it some time.”

Ray proclaimed his innocence until his death in prison in 1998.

©2023 Advance Local Media LLC.

Visit al.com.

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.