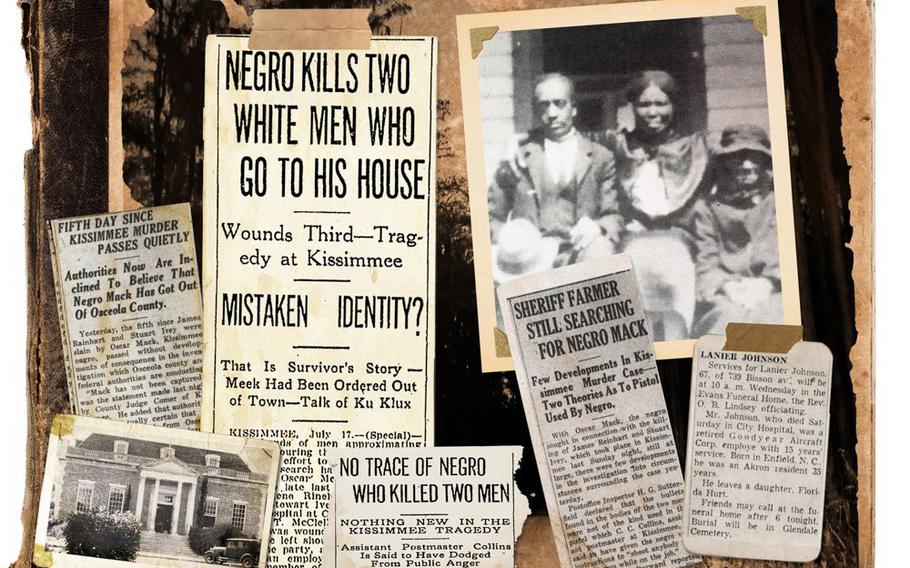

Photo illustration of newspaper clippings that ran in 1922 after Oscar Mack, a Black veteran of World War I, was confronted by members of the Ku Klux Klan in Kissimmee, Fla. Mack, pictured with his wife Adele Dorothy Keen, lived under the name Lanier Johnson after escaping from the attempted lynching. (Rich Pope, Orlando Sentinel/TNS)

(Tribune News Service) — It was a call 100 years overdue.

Renee Bronson is the great-granddaughter of Stewart Ivey, a Ku Klux Klan member killed by Oscar Mack, a Black postal worker. Her voice cracked as she began to say what she had carried with her for a long time.

“I’m so very sorry that someone in my family caused someone in your family to have to commit that act in order to protect his own life,” Bronson said. “I wish I could take that back. I deeply regret what happened there. It brings me great shame to think that someone in my family was involved in any kind of Klan activity. Growing up, I heard a story, but it was not the true historical facts.”

James Brown, Mack’s great-grandson, replied, “I thank you so much for your apology, even though you were not a participant. He was your ancestor. I think both families suffered as a result.”

The two-hour video call arranged by the Orlando Sentinel happened a century after Ivey and Eugene Reinhardt, another Klansman, were shot and killed after approaching Mack at his home the day he began working a federal contract as a mail carrier in Kissimmee.

A veteran of World War I, Mack received death threats after starting his new government job, which he got over white applicants. Few words were exchanged when a group of men arrived at Mack’s home before shots were fired. Reinhardt was killed at the scene, while Ivey named Mack as the shooter just before succumbing to his injuries.

A lynch mob searched the city for Mack, but by the end of the week, he was gone.

What happened to Mack was quickly lost to history. Many, including the NAACP, assumed he was caught by the mob and lynched, though his body was never recovered. The truth was carried only by Mack; his wife, Adele Dorothy Keen; and his stepdaughter, Florida Hurt, even decades after his death in 1960.

Bronson knew about the story from her grandmother, Ivey’s daughter, and believed Mack was killed by a white mob shortly after. She let out a sigh of relief when first approached for this story last August.

“Thank God no one else was a victim of hatred that day,” Bronson said.

Meanwhile, Brown and his siblings didn’t know what happened until 2001. Hurt, then 88, invited her grandchildren to her home in Akron, Ohio, where she told them what happened to the man they only knew and buried as Lanier Johnson. Details were plenty, but for years the family had forgotten Mack’s name.

Hurt died in 2007, leaving the story incomplete. Years later, the discovery of a project led by students in Orlando looking into Mack’s “lynching” sparked a sudden recollection by Hurt’s daughter, Malissa, revealing his real name.

By 2017, his grave was rededicated to include his true identity.

The Orlando Sentinel, working with researchers and Mack’s descendants, used property and tax records, military documents, census registers, news clippings and letters kept by relatives, among other traces of information, to help reconstruct the story of his life after he fled Kissimmee.

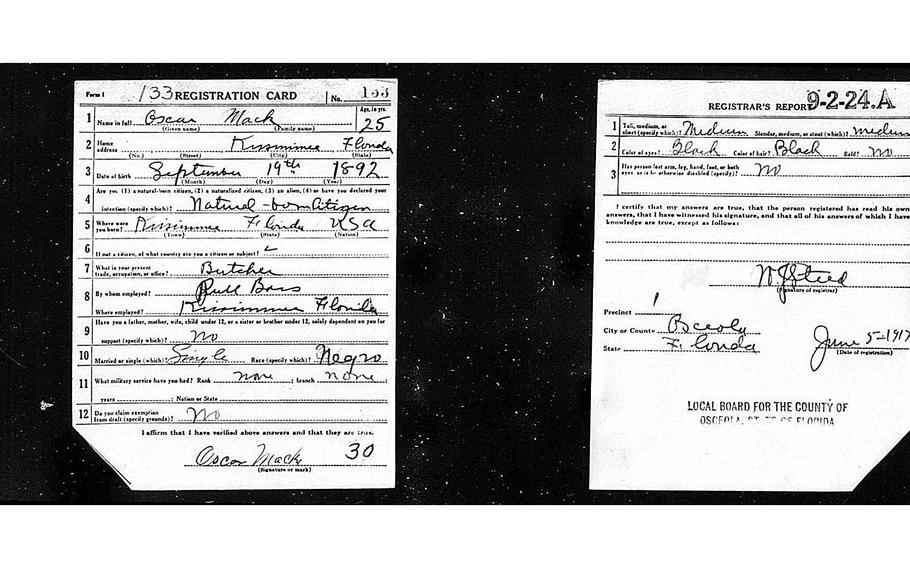

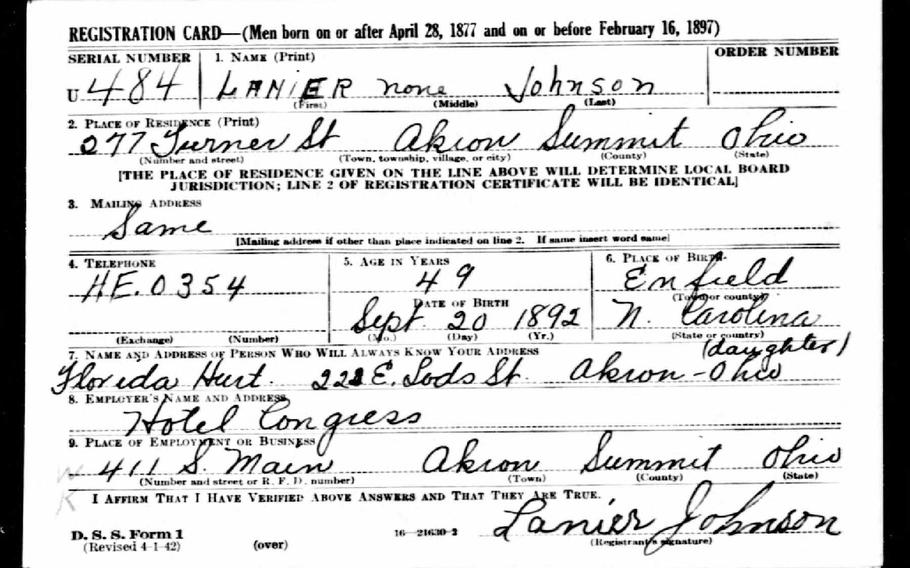

Oscar Mack’s World War I draft registration card. (Ancestry.com/TNS)

Years later, details of Mack’s tale are still being uncovered, and a documentary produced by the University of Florida is slated to be released in April. But Brown said he and his family don’t just want the story to be told and retold. What they want is reconciliation.

Meeting Bronson, Brown believes, is a significant step toward that goal.

“The reason I want it to be told isn’t because I want to just continue to fester the wound that’s already there,” Brown said. “I want it to be told because I want people to understand this is part of our history. This is what happened, and we need to learn from it.”

The killing of two Klansmen

It was July 16, 1922.

Kissimmee had just over 2,700 residents, over a quarter of whom were Black. Like much of Central Florida, the city was growing, as farmers and others, many from the North, migrated to settle in the decades following the Civil War.

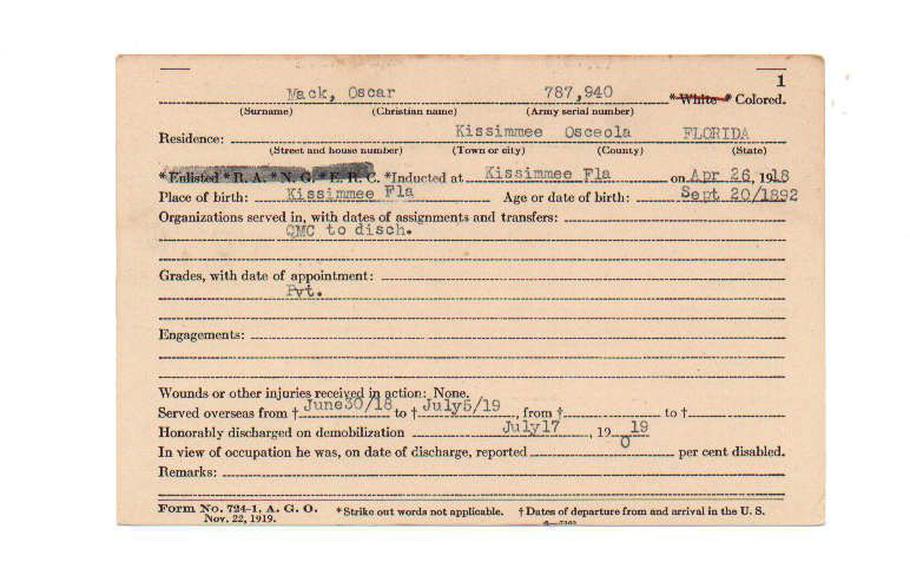

It had been years since Mack returned from France after serving in the U.S. Army Quartermaster Corps during World War I. Sons of a day laborer and a laundress, he and his brother, William Mack Jr., who also enlisted but stayed stateside, were named the year before in the Kissimmee Valley Gazette’s county roll of honor for their service.

Mack worked as a butcher for years after his return before winning a federal contract carrying mail between the local post office and the nearby train station. On his first morning at work, Mack was met by three white men.

Carrying the mail was a white man’s job, they told him, and that he should leave town by noon. Concerned, C.C. Collins, the white assistant postmaster hired almost a year earlier, handed Mack a gun to protect himself.

Undeterred, Mack made his rounds without trouble and returned to his home in Kissimmee’s north end, a largely Black community. Around 10:25 p.m., a group of men, including Reinhardt and Ivey, arrived at his home.

Five shots rang out. Reinhardt was killed instantly in his car. Ivey hobbled several blocks from the scene before collapsing on the porch of a woman’s home.

Benjamin McClelland, also a suspected Klansman who survived the shooting along with A.C. Alderman, said during a coroner’s inquest the men were searching for a different Black man who worked at McClelland’s turpentine still when they encountered Mack, who refused to answer when asked his name.

Instead, McClelland claimed, he “answered by a bullet.”

“The n----- kept on shooting,” he said, referring to Mack using a slur. But his account was contradicted by a doctor who tended to Ivey’s wounds and asked who shot him hours before Ivey succumbed to his injuries.

“It was a n-----,” Ivey said, according to the doctor. “Oscar Mack.”

Oscar Mack’s World War I service card. (State Archives of Florida/Florida Military Department/TNS)

By morning, about 200 Black people and their families rushed to the Kissimmee train station to flee the city in fear of a race riot, according to a report written by federal agent Leon Howe, who investigated the Election Day massacre that led to a similar exodus in nearby Ocooe just two years earlier.

Collins, the postmaster who gave Mack the gun used in the shooting, was taken to Tampa and then Jacksonville by federal agents under protective custody, while Osceola County Sheriff L.R. Farmer was tasked with keeping the peace as a roving white mob scoured the city looking for Mack.

Farmer went to Orlando to find George Scott, a Black man suspected of dressing Mack as a woman to help him escape. As they returned to Kissimmee, the mob took Scott and planned to hang him at Lake Jennie Jewel in Orlando before Farmer, convinced Scott was innocent of aiding Mack, persuaded them to let him go.

Though Farmer was suspected by some of already having Mack in custody, by the fifth day authorities admitted he likely left Osceola County.

The most detailed account of the shooting and its immediate aftermath comes from the Valley Gazette, a since-defunct weekly newspaper archived by the University of Florida. Still, many details about that day, including that the men likely knew who Mack was before reaching his home, were obfuscated by the Valley Gazette and other newspapers like the Orlando Sentinel.

The official narrative, per the Sentinel and others, was the shooting was “a case of mistaken identity.” Also reportedly “given little credence by the authorities” were Reinhardt and Ivey’s ties to the KKK.

“It is only another attempt to connect the Klan to a tragedy in which the organization was not concerned,” said an unnamed man the Sentinel referred to as someone “who has followed the investigation carefully.” Howe, who also investigated the Ocoee massacre two years prior, confirmed in later reports that Ivey and Reinhardt were members of the Orange County Klan, while McClelland was connected to Klan activity in Osceola.

Ivey was interred at Shingle Creek Cemetery in Kissimmee, Osceola’s oldest cemetery where members of the county’s pioneering families are buried. His funeral was attended by many, with his casket described as being adorned with floral emblems. Reinhardt was returned to his family in North Carolina, where he’s buried.

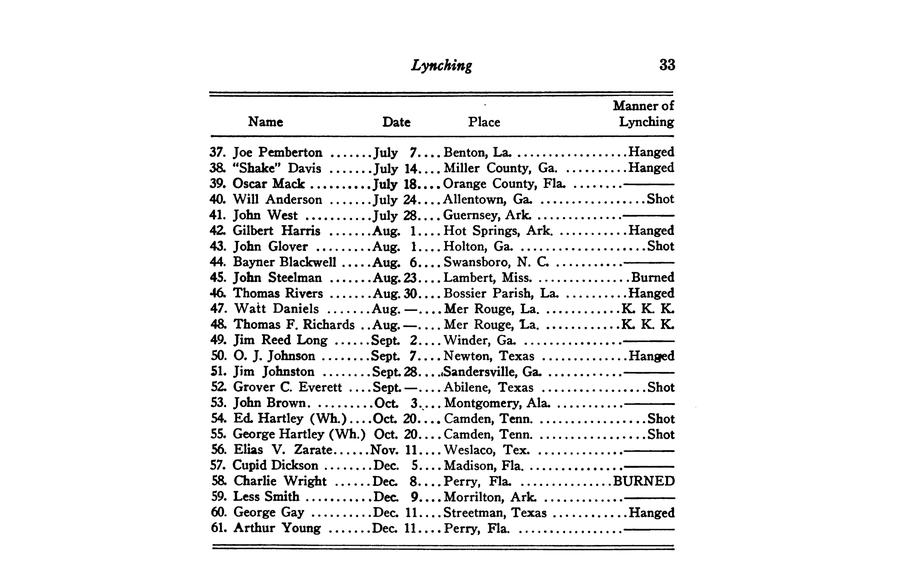

A manifest of lynching victims shows Oscar Mack reported as being lynched by a mob at Lake Jennie Jewel. The list was included in the NAACP’s 13th annual report published January 1923. (Orlando Sentinel/TNS)

Meanwhile, Mack was in the wind, dubbed a “negro desperado” in a brief published in the Ocala Evening Star. Rumors of him and Collins being lynched were quashed, though many — including the NAACP, which included Mack in its list of 61 reported lynchings in that year — believed initial reports that Mack was killed at Lake Jennie Jewel, even as his body was never recovered.

“When it comes to mysteries, Oscar Mack, the Kissimmee negro who is missing, vies with the Cyclops,” the Sentinel published on July 22, comparing Mack to the 1918 disappearance of the U.S.S. Cyclops, a Navy cargo ship that vanished during World War I.

It was also likely the last time Mack or the shooting were mentioned in local news reports.

‘Time to go, Old Man’

How Mack escaped is unknown. Brown said he and his siblings were told he made his way north through Florida’s swamps “guided by the spirit of his mother,” who had died months before Mack was sent overseas for the war effort.

At some point, he was joined by Keen and her daughter, Florida Hurt.

Mack and his family changed cities frequently throughout the 1920s, forced by Keen’s nightmares. She would dream about their capture at the hands of the Klan, which she took as premonitions that the mob were closing in on them.

“‘It’s time to go, Old Man,’ that’s what she would tell him,” said James Brown, Mack’s great-grandson.

Hurt eventually married at 15 and set roots in Akron. Brown recalled growing up hearing her say she got married so young after growing tired of constantly moving. “I wanted a stable life and a stable home,” he recalled her saying.

Her parents, still on the run, didn’t attend the wedding.

By 1928, Mack and Keen were listed in Akron city directories under his new name, “Lanier Johnson.” As Johnson, he stayed on the move, often splitting up for long periods from Keen, who for a while lived in New Jersey as he looked for work elsewhere.

Mack labored in whatever he could — at one point he was a chauffeur; at another, he worked at a general store — and would send money back to Keen. In 1934, he wrote a letter to President Franklin Roosevelt pleading for work, later receiving a reply directing him to local authorities as a jobs program created under the New Deal was demobilizing.

During their time apart, Keen wrote him often, at times pleading with him to return to her in Sicklerville, the New Jersey town where she lived. Mack eventually returned for good, and in 1938, they got married.

When the U.S. entered World War II, Mack, then 49 and an employee at the Hotel Congress in Akron, registered for the draft under his new name though he was never selected. Instead, he found work at the Goodyear Aircraft Company, one of many manufacturers that contributed to the wartime industrial mobilization. He and other workers there were awarded an Army-Navy “E” pin, for their work “to create the air power which turned the tide of battle.”

Oscar Mack’s World War II draft card, in which he was registered under his alias, Lanier Johnson. At the time he worked at the Hotel Congress in Akron, Ohio. (Ancestry.com/TNS)

As early as the 1930s, Mack and his family received letters from Meta Wideman, a woman who census records show lived in Daytona Beach with William Mack Jr., Oscar Mack’s older brother.

It’s not clear what relationship Wideman and William Mack had, nor where the elder Mack was when Oscar Mack fled Kissimmee.

The few surviving letters kept by Brown’s family don’t appear to address Oscar Mack’s escape, but they did indicate Wideman tried to visit Akron annually and had a strong friendship with the Johnsons, often sending them well wishes and offering updates from her and William Mack’s lives.

In February 1943, Keen, at 46, died of a brain aneurysm. Months later, Wideman wrote her widower, who she often lovingly referred to as “Brother Johnson.”

“[Bill] is so sorry; he sends much love, says that you have his heartfelt sympathy,” she wrote. “Don’t worry any more than you can help. I know that you will miss her. I miss her, and we can only trust God that we will meet her again somewhere in the land of peace and rest.”

William Mack Jr. later died at 60 in May 1951. He’s buried at Mt. Ararat Cemetery, a historically Black resting place in Daytona Beach. Wideman, who was also identified in records and newspaper accounts as Meta Mack, stewarded the cemetery’s upkeep as president of the Mt. Ararat Cemetery Association.

Though Wideman mentioned being very ill in her letters to the Johnsons, she lived several more decades and was an active member of her church until she passed in 1982 in Miami while visiting her son. It was reported in the Daytona Beach News-Journal that she would make periodic visits to Akron before she died, but Oscar Mack’s descendants don’t recall her being mentioned by relatives during that time.

Oscar Mack died January 1960, at 67. Unlike his brother, who was buried with a headstone marking his service in World War I, he died under his assumed name.

It’s not clear how he died, though at the time he was living in a nursing home and suffering from cognitive decline. Hurt recalled he would escape the home, hustling as if trying to flee the lynch mob he for years was certain was still looking for him.

After his death, he was laid to rest at Glendale Cemetery in Akron, finally free from his burden and, with his story largely unknown, certain his secret died with him.

“The respect I have for him, for this man who was able to escape, to fight for his life and have the tenacity not to give in, is immense,” Brown said. “He was a fighter. He was a survivor.”

‘Dirty’ Florida history

Oscar Mack’s story is not uncommon, though virtually nothing is known of others who changed their identities to escape racial terror.

That’s the point, said Richard Buckelew, history professor at Bethune-Cookman University who serves as a historian documenting lynchings for the Volusia Remembers Coalition.

“If they’re any good at it, you wouldn’t hear about it until something like this comes up,” Buckelew said. “Understanding the situation and the times, it happened a lot more than we think.”

Florida was notorious for lynching. Between 1880 to 1940, it had the second-highest rate of lynchings targeting Black Americans in the country, while Orange County ranked seventh in the nation in total lynchings within the same period, according to a report by the Equal Justice Initiative.

The state is also home to several incidents of racial violence, many happening within a few years of Mack’s disappearance — the 1916 lynching of the Newberry Six, the 1920 Election Day massacre in Ocoee that almost overnight turned the city for decades into a sundown town, the razing of Rosewood’s Black community in 1923, among others.

Often, news accounts describing alleged violent crimes against whites by Black people referred to the latter as “desperadoes” where the term wouldn’t exist in the reverse context. Subsequent lynchings and flaring racial tensions would be downplayed — like in Mack’s case, where ties to the KKK were quickly dismissed by reporters at the time.

“Look at what the Orlando Sentinel did with the Groveland Four, with that famous cartoon with the electric chair before they were even indicted. That image went all over the world,” said Marvin Dunn, professor emeritus at Florida International University and a prominent historian of anti-Black violence in Florida. “The media helped establish the normalcy of lynching by advancing the view that the person deserved it.”

Lynchings were often public spectacles, even a family affair where parents would take children to watch Black people be killed, usually before they had their day in court. Many were immortalized through postcards and newspaper accounts lending sympathy to white mobs.

It was also common for spectators to take souvenirs from the people who were killed, including body parts that were later preserved as keepsakes, Buckelew said.

“It really wakes you up to a sense of how depraved our culture was,” he said.

And in Florida, like other places where lynching was common, there were many who would rather not address the practice.

“There was a lot of dirty Florida history in lynching that a lot of people, for good reason, did not want brought up,” said Dunn, author of “The Beast in Florida: A History of Anti-Black Violence.” “In part, it’s because some of their own relatives were involved in it or, at least, knowledgeable of it but did not speak out against it.”

Weeks before Mack fled Kissimmee, a federal anti-lynching bill passed the House of Representatives years after it was first introduced in 1918. It would have made lynching a federal crime at a time when the practice was emblematic of the nadir of American race relations.

The 1922 bill failed in the Senate with the staunch opposition of Southern Democrats. It was among more than 200 attempts to outlaw lynching federally before the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act was signed into law last year, making lynching, now a largely uncommon phenomenon, a crime carrying a 30-year prison sentence.

“You can pass it now because it doesn’t mean anything, it’s good publicity,” Buckelew said. “It’s like passing an anti-slavery law now. It doesn’t have much effect.”

The Equal Justice Initiative recorded more than 4,000 lynchings of African Americans between 1877 and 1950 in 12 states making up the American South. Lynchings were less common by the 1950s, though high-profile examples like Till’s murder in 1955 figure prominently in the public conscience.

In recent years, Buckelew’s work with the Volusia Remembers Coalition helped unearth previously undocumented cases in Volusia County. Cases like the 1939 lynching of Lee Snell, a taxi driver beaten and shot as he was being escorted to jail for allegedly hitting a white boy riding a bicycle, is one of five memorialized by collecting soil from the sites and donating them to the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Ala.

Attendees lined up to shovel into jars soil from the site where Lee Snell, a Black entrepreneur and World War I veteran, was lynched by a white mob in 1939. The webinar honoring Snell’s life and highlighting his death was hosted by the Volusia Remembers Coalition on Saturday, Feb. 27, 2021. (Screenshot from webinar, Orlando Sentinel/TNS)

The usual starting point for researchers like Buckelew is newspaper accounts. But the challenges in finding many of the records mean any estimates in the number of lynchings are likely to be conservative.

Those fortunate enough to escape, like Mack, would flee the area and change their identities to avoid detection. Also like Mack, whose name was recorded in a 1923 NAACP report as having been “lynched by a mob,” loved ones who stay behind often don’t dispute the reported deaths.

It was a defensive mechanism, Dunn said, one which he understands intimately. In the 1920s, his grandparents fled south Georgia to Orlando after his grandfather killed a white man, but he would sneak back under the cloak of night to visit his family over holidays.

“This went on for years,” Dunn said. “There were Black men who would leave but then maintain ties with their families which would be kept secret by everybody to protect that person.”

Dunn doesn’t know his grandfather’s name, only knowing him by his alias, Buck Williams. Anyone who would have likely known his real name has long since died, he said.

Unlike Mack’s great-grandchildren, who were eventually able to piece together Mack’s true identity, Dunn and others might never be able to.

“In a sense, it means I’m not quite sure who I am,” Dunn said. “There’s no way of filling that in, everybody’s dead now. Many, many Black families in the South have had the same experience, and one reason why it’s not all that well known is because it’s not supposed to be all that well known.”

Finding Oscar Mack

Renee Bronson grew up knowing the story about the night a Black postal worker killed her great-grandfather, Stewart Ivey, from her grandmother, who was 8 when he and Reinhardt were shot dead.

Marguerite Ivey Bronson, Stewart Ivey’s daughter, told the story to her grandchildren, referring to it as “the night that n----- shot your granddaddy.”

Much of Bronson’s understanding of what happened matches with what the Brown family later learned, but she long wondered if Oscar Mack had escaped or, as many at the time assumed, he had been caught by the lynch mob.

Finding out he survived, Bronson said, brought her peace.

“All my life I thought he had been lynched, and that made my burden of guilt by heritage so much heavier and so much harder to carry,” Bronson said. “When I heard he survived and went on to raise a family, I was thrilled.”

For years, many in Mack’s family besides his wife and stepdaughter didn’t know what really happened. Mack’s grandchildren for a long time only knew him as Lanier Johnson, and his great-grandchildren were only kids the day he died in 1960. At some point, Malissa Hurt, one of Mack’s grandchildren, was told the story of his true identity and kept it to herself before sharing it with her nephew, Marvin Brown, at a wedding in 1999.

“We sat at a gazebo, and she began to share with me what Grandma told her and how long my grandmother kept it a secret,” he said. “She was told never to mention it to anyone but that [my grandmother] wanted her to be aware of it.

He told the Sentinel he didn’t know what to make of it at the time, since Hurt had forgotten her grandfather’s real name until many years later. Mildred Hurt, Malissa’s sister and matriarch of Brown’s family, died without knowing Mack’s story.

Florida Hurt, Mack’s stepdaughter, divulged more details at her Akron home in 2001. The elder Hurt died six years later, at 94.

From there, James Brown, known by his relatives as the family historian, got to work, trying to find any cases from the 1920s involving a Black man escaping a lynch mob.

“It just stayed with me,” he said. “My grandmother was able to give us a lot of information, but I wanted to delve into it a lot further.”

Unknown to him and his family, a group of students at Rollins College led by history professor Julian Chambliss began investigating the 1922 shooting. The class project, assigned in 2013, began with a single newspaper clipping found by Curtis Michelson, a researcher with Democracy Forum.

The clipping was in a pile of material collected as research of the Ocoee massacre by Democracy Forum, which made significant contributions in the late 1990s to how that event is understood today. It didn’t come up again until Michelson was reminded of Lake Jennie Jewel, which sits next to Orange Avenue near Holden Heights, along the route where Michelson would ride his bike.

From there, the students spent a semester looking into the shooting and Mack’s subsequent escape from Kissimmee. They scoured newspaper accounts and dove into census and other records available on sites like Ancestry.com, to piece together the life of the Black World War I veteran forced to flee his hometown.

“I wanted to make it a pure student project that was guided by Julian and I, and that turned out to be really good,” Michelson said.

But without a death certificate confirming Mack was killed that year, and conflicting accounts of his demise — including Howe’s reports, which assumed Mack was likely dead and were mentioned in a 2008 book about anti-Black violence in the 20th century — the project hit a dead end.

Chambliss, who now teaches English at Michigan State University, said that is partly explained by inconsistent record keeping about Black people. The distortions in how Mack was portrayed in contemporary news reports further presented a challenge in telling a more complete story of who he was and what happened that night.

“The normal mechanisms that are used to document people are often not used to document Black people, or really any people of color, throughout American history,” Chambliss said. “You’re forced to sort of seek them and humanize them through a variety of means. That’s really complicated, especially when you’re telling a story of racial violence, because Black people are victims and you’re trying, as best you can, to tell their human story with the data that you have.”

A website created to publicly document the project’s findings sat online and was about to be taken down when, in 2014, there was finally a breakthrough. Back in Akron, the Brown family stumbled on the site and pored over the stories about a suspected lynching in Kissimmee and the Black man who may or may not have survived it.

They read out Mack’s name and Malissa Hurt, her nephew recalled, was ecstatic.

“She said, ‘That’s it, that’s the name! I got chills.’ I’ll never forget that,” Marvin Brown said.

James Brown reached out to Michelson soon after, who connected him to researchers at the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program at the University of Florida. And for the next three years, Chambliss, Michelson and the team from UF worked with the Brown family to fill the gaps in the tale of Mack’s life.

Many of the records kept by the Brown family are now archived by the university.

“My grandmother held on to all that information; we have the letters, we have everything,” James Brown said. “I guess she held on to it not really knowing that one day this would probably become news.”

The bridge of freedom to love

Marvin Brown recalls few details from when he attended the funeral of the man he only knew as Lanier Johnson, held at Glendale Cemetery in Akron on Jan. 6, 1960. It was cold and breezy that morning, and the ceremony was attended by a small group of relatives.

Johnson “died a pauper,” recalled Marvin Brown, who was a child when he attended the funeral with his mother. He remembers Johnson being laid in a metal casket that “wasn’t considered top of the line.” He didn’t know who Johnson was at the time, as he and his siblings had virtually no contact with Johnson before he died.

Malissa Hurt, Oscar Mack’s granddaughter, remembers him as a quiet, kind man who would speak lovingly with his grandchildren, often about their schooling, the few times they would visit him. His surviving great-grandchildren don’t remember meeting him at all.

“It was my first time ever seeing someone being lowered into the cold ground, and that was the first time I learned of his existence,” Marvin Brown said. James Brown, his brother, said their mother, Mildred Hurt, “never really talked about him” either.

“He was just Mr. Johnson,” James Brown said.

That is, until June 28, 2017.

Unlike the day of his funeral, this one was warmer, less windy and had fewer clouds in the sky as Malissa Hurt, the Brown family, their friends and the researchers arrived at his grave.

Johnson had rested there undisturbed for decades, his secret all but lost to history. That day, his family replaced his gravestone to include his given name while Chambliss, Michelson and the documentarians from UF observed.

It was a redo of his funeral. Those in attendance were dressed in black. Hymns were sung and eulogies were read. The Rev. Alexis Brinkley-Felder, a longtime friend of the Brown family who witnessed as they pieced together Mack’s story, presided over the ceremony.

But the atmosphere wasn’t somber. Instead, it was a celebration of Mack’s life and an acknowledgment of his struggle. His alias remained on the stone, to recognize the identity he took on after he was forced to leave Kissimmee.

“We all have this gap as African-Americans that we can’t identify and no one can tell us,” said Brinkley-Felder, who spoke on Mack’s journey in her eulogy. “So when we put someone’s story together, we feel like we’re closer to our own story.”

It’s a story further memorialized in a poem read at the funeral written by Vanessa Bonner, Mack’s great-granddaughter. Called “The Bridge of Freedom to Love,” it’s a retelling of Mack’s journey, that of a soldier returning from war only to fight another for his life.

It began:

I fought to live but riddled in fear

Shadows of my past haunted me within

Forced to flee by fight that night

I sought for help by a spirit of light

She showed me the way from a bright star above

For which brought me to a place of safety and love

“I felt the presence of someone else driving me to write this poem and I could see him running, I could see the woods, I could feel the dampness,” Bonner said of the piece. “I could see the moonlight and it’s piercing through the trees at night. I could feel the fight in him, that he was being directed, and I can just feel him surviving.”

During the trip to Akron, the researchers visited Malissa Hurt’s home, where boxes of photographs, letters and other documents belonging to Mack and stored in an attic were copied while she and her family gave on-camera interviews.

The material they collected that day is archived by UF and will be part of a documentary scheduled to screen in April, six years after the rededication ceremony. Deborah Hendrix, who has been with UF’s oral history program since 2005, is leading its production.

Far from her first foray in uncovering Black stories of fighting back against racial terror, Hendrix said Mack’s “is not a normal story,” echoing the experts who said his experience is not meant to be well-known, sometimes even by family. The fact his story is known at all, and the way it came to be known, is largely unheard of.

“The whole day was like you were going to the funeral of someone who had just passed away,” Hendrix said of the rededication ceremony. “In a metaphorical and literal way, that’s what it was, the passing of the fictitious person and coming full circle. And it’s not the last chapter.”

At the rededication ceremony, James Brown spoke about his desire for reconciliation for Mack by remembering his story and learning from it. And before they met, Bronson had been working with her local church toward what she called “annihilating racism.”

Their nearly two-hour conversation was the first of what they hope will be many to come. She and the Brown family hope to meet during the documentary screening, to which they were both invited.

“The thing that pains me is the beast is still alive in our culture,” Bronson said. “We still have hate crime, we still have hatred and we still have a lot of people with some very distorted ideas about what justice is and what equality and fairness are.”

“I often say the color of racism is nothing more than fear,” James Brown told her. “I’m sitting here and listening to you, and it’s really helping me. … It bothers me that people still look at me based on my color.”

There are still many unanswered questions about Mack’s story. How did he escape Kissimmee so quickly and without detection? Where was his brother during the ordeal, and how were they able to reconnect once Mack left the state? Did Meta Wideman’s family know who she was writing to and visiting in Akron?

They are questions that might never be answered, but Mack’s tale offers another perspective of a tumultuous era in the history of U.S. race relations. His escape from Florida, Michelson said, was part of the Great Migration, in which millions of Black Americans left the South over decades, in part to escape the violence that came with Jim Crow.

“All of this violence is happening; we all feel it, but people of color lived in that kind of trauma in a way whites did not and everybody shared it,” Michelson said. “Oscar Mack’s story is that of survival and making a way where there was no way.”

For Chambliss, Mack’s journey, like many told throughout history, is tragic. There’s no way to reliably tell how many people were lynched or were otherwise victims of anti-Black violence, which he fears “might be a lot larger than we’re all willing to comprehend.”

But Mack’s story ends with a different outcome, Chambliss said. He survived. He was able to raise a family. His descendants went on to build their own lives while carrying — unknowingly, for years — his legacy of survival and resilience.

With that, and through the connections made with researchers in Orlando, they were able to uncover his story and return to him his identity. Even many years after the Brown family first learned about their great-grandfather, they hope new details emerge to fill the remaining pieces of the puzzle.

“We have, at some level, pulled together a story of Oscar Mack,” Chambliss said. “It’s not necessarily the complete history that it could be, but his humanity is restored.”

creyes-rios@orlandosentinel.com

©2023 Orlando Sentinel.

Visit orlandosentinel.com.

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.