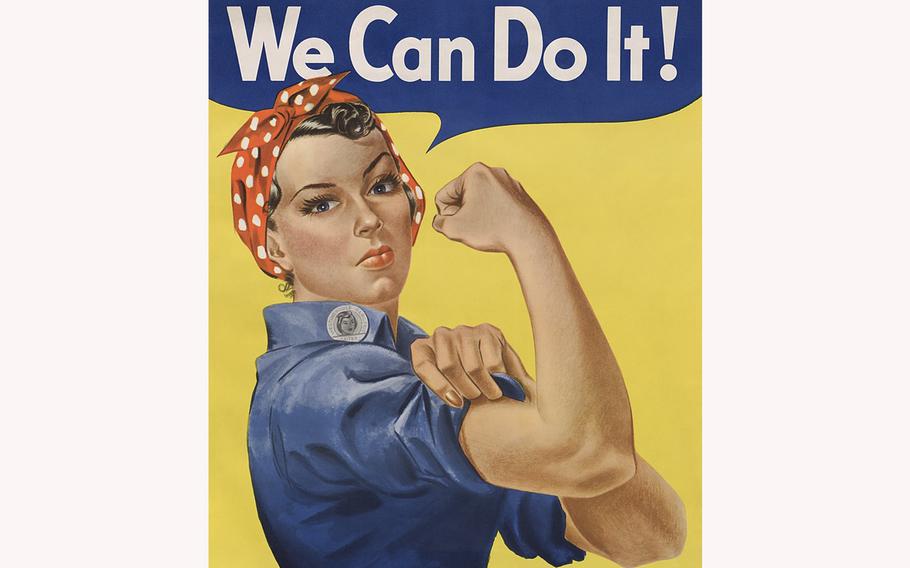

“We Can Do It!” by J. Howard Miller, was made as an inspirational image to boost worker morale during World War II. (WikiMedia Commons/Office for Emergency Management. War Production Board.)

VACAVILLE, Calif. (Tribune News Service) — Her cheerful face, wide smile and perfectly coiffed hair were every bit a match for the temporary decor in her Suisun City living room: dozens of bright floral bouquets, birthday cards arrayed like proud affirmations on the dining room table and clusters of balloons rising to the ceiling.

But one black metallic balloon with white numerals denoting 100 said it all, explaining the reason why Elizabeth Tate was in a reflective mood just a few days after her 100th birthday.

Seated at the dining room table in a tan sweater dotted with sequins over leopard print pants, Tate, who is slightly hard of hearing and suffers from Type 2 diabetes, was frank about her current well-being even though her hitting the century mark has prompted a newsworthy celebration, some of it still pending.

“I’m sort of out of it today,” she said matter-of-factly, with daughter Rella Rosboro seated nearby.

Amid her greeting cards was a family photo of the wedding of Rosboro’s brother’s oldest grandchild, and begged for an explanation.

“It was a super spreader event,” said Rosboro, as Tate smiled at the recollection and the photo showing some two dozen people. “Everybody got COVID except Elizabeth!”

Her mother remains active and “is constantly on the computer” and is still asked to give recitations and poems at various public events in Suisun City and Fairfield, she said.

A former Rosie the Riveter who worked in the U.S. defense industries during World War II, Tate will have another birthday celebration at 3 p.m. Feb. 25 in the Delta Breeze Club on Travis Air Force Base, noted Rosboro. And Tate will be feted again, along with other Solano County centenarians, at 9 a.m. Feb. 28, by the Board of Supervisors in their County Government chambers, 675 Texas St., Fairfield.

Just by sheer longevity, Tate’s is a remarkable survivor’s tale.

She is someone who has passed through the major events of the 20th century and those of the first 23 years of the 21st, from the first sound-on-film motion picture (1923) to the Cold War and the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and ‘60s, to the COVID pandemic and deeply divided American politics (2023), and the ongoing, mind-boggling advances in medicine and ever-changing American culture.

Elizabeth Fisher Tate was born on Feb. 2, 1923, in Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana. Immediately after her birth, her family moved to New Orleans, living in the Ninth Ward, in the easternmost part of the city, an area that in 2005 made national news because it was devastated by Hurricane Katrina.

During the interview, Tate said she lived “in a ‘shotgun house,’ “ a narrow house common in Black communities in New Orleans, laid out so, she added, “If you opened the front door, you could see (unobstructed) all the way back to the backdoor.”

She attended public schools there, graduating from McDonogh 35 High School, where, according to her family biography, a prepared statement, the principal was Lucien Alexis, a Harvard graduate. He could not find a job with his Ivy League degree, “so he shared his scholarship, discipline and scientific theories with his students.” Tate graduated in 1940 at age 17, when war was approaching and the first peacetime military draft in U.S. history was approved.

But Tate said it was unclear the global conflict, already underway in Europe, would involve to the United States.

Shortly afterward, with her father’s blessing, Tate responded to a National Youth Administration newspaper ad “focused on providing education and work for youth, ages 16 to 25.” The NYA was part of the Works Progress Administration, one of Roosevelt’s New Deal agencies created in the 1930s during the Great Depression. It included a Division of Negro Affairs headed by Mary McLeod Bethune, who later founded Bethune-Cookman College in Florida and the National Council of Negro Women. Bethune also befriended first lady Eleanor Roosevelt.

As part of the NYA, Tate traveled with six other girls from New Orleans by train, leaving the city for the first time in her life, to Washington State, where she learned to operate a lathe. Later, with a valuable skill on her resume, she moved to Richmond, where her oldest sister lived, but didn’t like the East Bay town. So she moved to San Francisco, where she landed a good-paying job making bolts for the war effort at the Hunter’s Point Naval Shipyard.

“I made a lot of bolts,” said Tate, smiling. “Tubs of bolts.”

After the war, she worked for more than two decades at J.C. Penney, the first Black woman in management at the Daly City store, retiring at age 60. To this day, she still receives a pension from the department store — “And a discount” when she purchases store products, she said, smiling at the thought.

Tate married Webster Rosboro and together they raised Rella and Webster Jr., but the elder Rosboro died in December 1970. Tate remarried in 1975 to James Tate, a retired airman, and settled in Solano County. He died in July 2020 but not before receiving recognition from Rep. John Garamendi for his many years of military service.

Rella Rosboro noted that on March 15, 2022, Rosie the Riveter Trust Executive Director Sarah Pritchard, introduced the Wall of Honor at the Rosie the Riveter National Historical Park on Harbour Way in Richmond. The wall was designed and built to honor a past or living female World War II worker by having a banner featuring a photograph and brief bio of a Rosie.

“Elizabeth’s banner was proudly displayed on the wall,” Rosboro said in an email to The Reporter. Five Rosies, including Elizabeth Tate, were on the dais as Pritchard explained the wall’s purpose. Each Rosie was introduced to the audience. Afterward, a documentary about the Rosies, still being developed and edited, had a special viewing, she said.

Tate is a member of the Mount Calvary Baptist Church in Fairfield. There, on Feb. 5, three days after her 100th birthday, the pastor, as seen in a video of the occasion, honored Tate in front of the congregation, describing her as “sharp, sassy, sexy, suave” and “spiritual.”

Pastor Claybon Lea and others sang a version of Stevie Wonder’s “Happy Birthday,” with its infectious R&B rhythms and plenty of balloons around, with Lea telling Tate that the church community had been, among other things, “so enriched by your wisdom, your teaching.” He then presented her with a $1,000 check.

“I love my congregation,” Tate can be heard seen in the video. “I ask that you pray for me.”

Tate’s cousin, retired Marine Corps Chief Warrant Officer 4 Clyde L. Fisher, called her on her 100th birthday, telling her she is “our Fisher relative” and “100 of 277 years in the Fisher family,” he wrote in an email to Rella Rosboro.

Through genealogical research, he noted that Tate is the fifth great-granddaughter of Anthony Fisher, born in 1745, in Tanzania, Africa, “a free enslaved person” who died in 1850 at age 105 in the township of Ivor, Southampton County, Virginia.

“Mrs. Elizabeth Fisher Tate is unique and very proud of her heritage and family,” Clyde Fisher wrote, adding, “ Mrs. Tate’s service to the United States during WWII is highly admirable.”

As to her memory, Tate attributed it to reciting a poem every night, and, accounting for her longevity, she said, “I’m a person who thinks positively. I love everybody. I don’t have time for picking and choosing stuff. I have God in my life.”

(c)2023 The Reporter, Vacaville, Calif.

Visit The Reporter, Vacaville, Calif. at https://www.thereporter.com/

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.