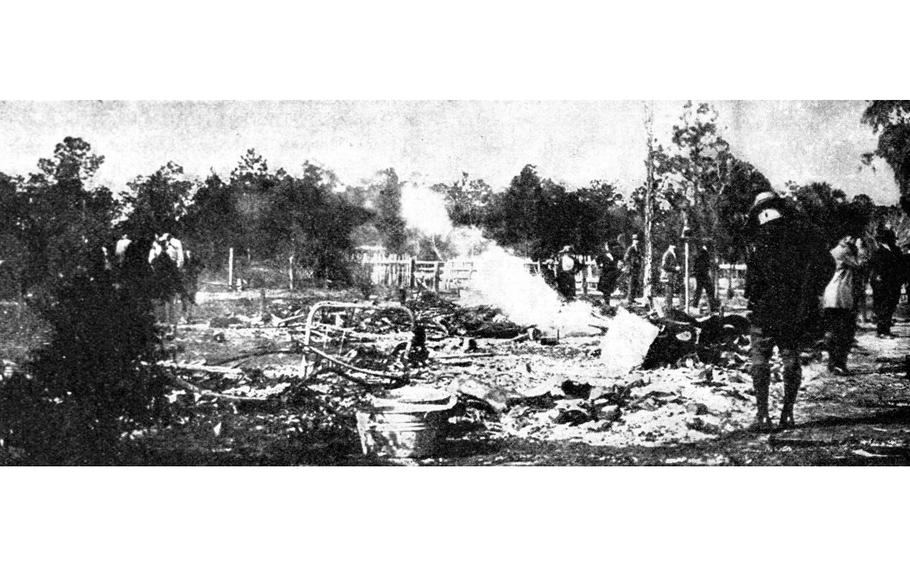

The ruins of a burned house in Rosewood, Fla., in January 1923. (State Archives of Florida)

In January 1923, a white mob descended on the predominantly Black town of Rosewood, Fla., torturing and killing Black residents. In its seven-day reign of racist terror, the mob torched Black-owned houses, churches and businesses. Some Black people hid in swamps and woods to escape violence so destructive that, 100 years later, all that is left standing of the entire town of Rosewood is a scorched landscape containing a historic marker and a single house.

That two-story house once belonged to John Wright, a white resident and store owner in Rosewood who hid Black people escaping the white mob until they could board a train out of town.

“What happened in Rosewood is a sad story,” said Lizzie Robinson Jenkins, 84, the president of the Real Rosewood Foundation, a nonprofit organization dedicated to preserving Rosewood’s history. “It’s an ugly part of history, but it’s one everybody needs to hear.”

Jenkins’s aunt, Mahulda Gussie Brown Carrier, who worked as the schoolteacher in Rosewood, was assaulted in the massacre. “It has been a struggle telling this story over the years because a lot of people don’t want to hear about this kind of history,” Jenkins said. “But my mother told me to keep it alive, so I keep telling it. We have to keep our history alive.”

The official death toll of the Rosewood Massacre, which began on Jan. 1, 1923, is listed by the state of Florida as five Black people and two white people. Some historians believe many more Black residents were killed — possibly hundreds.

The pogrom in Rosewood followed other racist terror massacres across the country, including the 1908 Springfield Massacre in Illinois; the 1917 East St. Louis Massacre in Illinois; the 1919 Elaine Massacre in Arkansas; the 1920 Ocoee Massacre in Florida; and the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre in Oklahoma.

Before the massacre, Rosewood, near the Gulf of Mexico, was a town of about 100 people where some Black residents owned land and houses, surrounded by vegetable gardens and orange trees.

The Wright House is all that is left of Rosewood, Fla., after the 1923 massacre. (Lizzie Robinson Jenkins)

The massacre was ignited by a false accusation from Fannie Taylor, a white woman who lived in the nearby predominantly white town of Sumner and claimed she’d been beaten by a Black man.

“Her husband came home and found her bruised,” Jenkins said. “But the bruises came from a white lover. Her lover knew trouble was brewing and gave a run for it.”

A 1997 report in the Florida Historical Quarterly said that Sarah Carrier, a Black woman working in Taylor’s home, and Carrier’s 11-year-old granddaughter Philomena Goins witnessed the white man leaving Taylor’s house that morning.

“Fannie Taylor was white; Sarah Carrier was black,” stated the report, written by Maxine D. Jones, a professor of history at Florida State University. “In such a situation Carrier’s word counted for little.”

Philomena, who’d gone to work with her grandmother to do laundry at Taylor’s house, “saw a white man enter and later leave Taylor’s house that morning,” Jones wrote. She also “watched as Fannie Taylor convinced Sumner whites that she had been assaulted by a Black man.”

Meanwhile, Taylor’s husband, James Taylor, a foreman at a local mill, telegraphed Ku Klux Klan members gathered in nearby Gainesville to ask for help, Jenkins said. “Somebody called the prison camp and requested dogs be sent to Sumner,” she said. “The white mob organized in Sumner before going to Rosewood.”

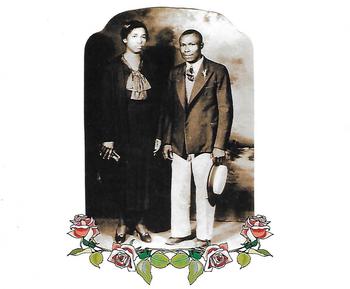

The white man leaving the Taylor house fled via Rosewood, stopping at the home of Aaron Carrier, a Black man who worked as a crosstie cutter, according to Jenkins, who is Aaron Carrier’s niece. The man knew Carrier was a mason and so gave a masonic knock, prompting Carrier to jump out of bed, Jenkins said. “He opened the door and saw a white face and panicked,” she said.

Family photo of Mr. and Mrs. Aaron Carrier, Rosewood survivors. (Lizzie Robinson Jenkins)

Carrier went next door to find Sam Carter, who had a wagon, and they took the white man to his hometown of Gulf Hammock. Later that evening, the mob caught Carter on his way home and shot him to death, Jenkins said.

Another mob tried to attack Carrier, but the Levy County sheriff interceded and drove Carrier to Gainesville, where he asked the local sheriff “to put him in jail for safekeeping for six months in Gainesville,” Jenkins said. Carrier would survive the massacre.

But the mob killed his father, James Carrier. “They shot him right where they saw him in the road,” Jenkins said.

On the second day of the massacre, Sarah Carrier’s son Sylvester Carrier held off an attack on his mother’s house, firing from inside the house. Sarah Carrier, a pillar in the community, was killed that day, as were two white men, Poly Wilkerson and Henry Andrews, according to a state report.

The mob set fire to Sarah Carrier’s house, then burned every Black-owned house in Rosewood. “They burned all the houses down, after they stole everything out of their homes,” Jenkins said. Sylvester Carrier escaped on a slow-moving passenger train sent through Rosewood and other communities to pick up Black people escaping the violence and take them to Gainesville.

According to a historical marker in the Harry T. & Harriette V. Moore Memorial Park in Mims, Fla., “Many of the black residents of Rosewood who fled to the swamps were evacuated on January 6 by two local train conductors, John and William Bryce. Many others were hidden by John Wright, the owner of the general store.”

During the rampage in Rosewood, a white mob fatally shot Lexie Gordon, a Black widow who’d fled after the mob set her house on fire. “She was trying to run to save her life,” Jenkins said, “and they killed her.”

White people driving toward Sumner shot Mingo Williams, who, according to some records, was 49. “They shot him just because he was Black,” Jenkins said.

On Jan. 29, 1923, Gov. Cary Hardee (D) ordered an investigation. But a grand jury declined to issue indictments. No one was ever prosecuted for any of the killings or arson in the Rosewood Massacre.

“They never rebuilt,” Jones said. “None of the Black people went back there. Those who owned property lost their land. There is nothing there now.”

In 1994, Gov. Lawton Chiles (D) signed a $2.1 million compensation bill. Nine survivors received $150,000 each. A state university scholarship fund was established for the families of Rosewood survivors and their descendants.

In 2004, after 30 years of work, Jenkins persuaded Florida to erect a historical marker on the site of what is left of Rosewood. “Whites burned Rosewood and looted livestock and property,” the marker states. “Two were killed while attacking a home. Five blacks also lost their lives: Sam Carter, who was tortured for information and shot to death on January 1; Sarah Carrier; Lexie Gordon; James Carrier; and Mingo Williams. Those who survived were forever scarred.”

The painful memories of the racist terror massacre lingered for generations. “I was angry when my mother told me I had to keep telling this story,” Jenkins said. “But she said, ‘You’ve got to do it.’ ... People today are still suffering, because it was just inhumane.”