Horatio Greenough’s statue of George Washington, between 1918 and 1920. (Library of Congress)

Slowly, some of the U.S. Capitol’s many statues and other artworks honoring enslavers have been slated for removal, most recently a bust of Roger B. Taney, the chief justice who authored the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision denying Black people citizenship.

But the first statue Congress voted to remove from the Capitol was one of George Washington — not because Washington was an enslaver but because the statue was scandalous.

The first president was portrayed naked to the waist in a toga with his right finger pointing toward the sky and his left hand clasping a sheathed sword.

“The man does not live, and never lived, who saw Washington without his shirt,” complained Rep. Henry Wise, a Virginia Democrat.

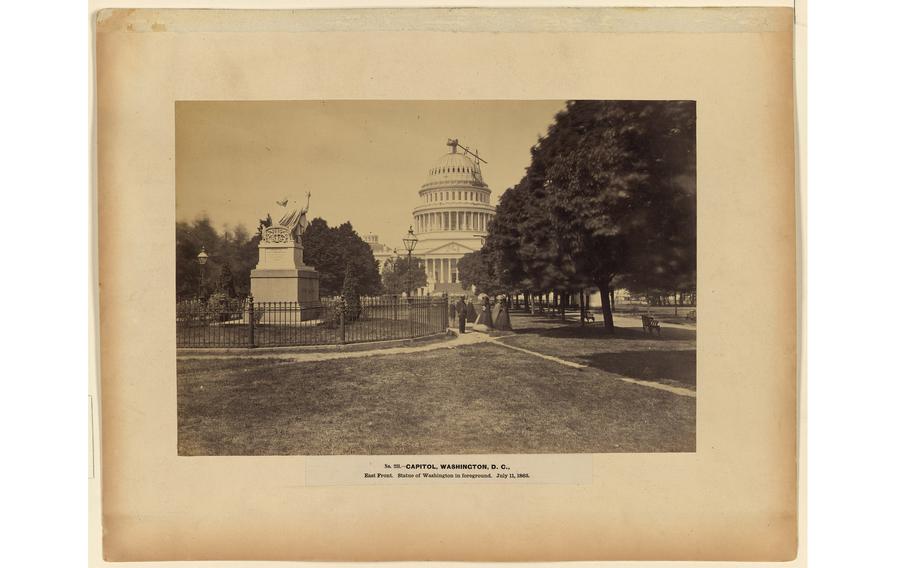

Of the thousands of statues of Washington, this one, by American sculptor Horatio Greenough, is the most controversial. To mark Washington’s 100th birthday, in 1832 Congress authorized the creation of what it expected to be a reverent rendition of the United States’ most revered founder. President Andrew Jackson picked the 27-year-old Greenough for the task, and Greenough labored on his creation in Italy for more than eight years. When his 12-ton marble statue was squeezed into the Capitol Rotunda in late 1841, during the presidency of John Tyler, many onlookers were aghast.

The 12-foot-high statue showed Washington’s head atop a very buff and bare-chested body, resembling a Greek or Roman god. He sat on a chair wearing sandals and a toga, part of which was draped over his bent right arm.

“I fear this statue will only give the idea of entering or leaving a bath,” said Charles Bulfinch, the former architect of the Capitol, and should be sent to Athens “to be placed in the Parthenon with other naked great men.” Former New York mayor Philip Hone wrote in his diary that the statue looked “like a great herculean Warrior — like Venus of the Bath — undraped, with a huge napkin lying on his lap.” Sen. William Preston, a South Carolina Whig, called the statue “the most horrid phantasmagoria I have ever beheld.”

A view from behind of a statue of George Washington by Horatio Greenough in front of the U.S. Capitol under construction on July 11, 1863. A group of sightseers stands nearby. (Library of Congress)

People were shocked to see the great general in the buff.

“Did you ever see Washington naked?” wrote author Nathaniel Hawthorne, tongue in cheek. “It is inconceivable. He had nakedness, but I imagine was born with his clothes on and his hair powdered and made a stately bow on his first appearance in the world.” When British author Charles Dickens visited the statue in 1842, he wrote, “It has great merit, of course, but it struck me as being rather strained and violent for its subject.”

Not everybody hated the statue. Essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson described it as “simple & grand, nobly draped below & nobler nude above.” Emerson agreed with Greenough that the problem was the poor lighting in the Rotunda, especially with the statue perched atop a 13-foot wooden platform. On Jan. 11, 1843, the two men made a nighttime visit to view the colossal statue by torchlight. It did not go well.

“Higher, higher,” Greenough shouted to the lamp holder, according to House historians, who wrote, “Soon, flames leapt from the lamps to the wooden box and pole that held them aloft.” The box, Emerson wrote a friend, was “let down rapidly, lamps melting & exploding & brilliant balls of light falling on the floor.” The two men dragged the “brilliant bonfire” safely outdoors, he wrote.

Greenough lobbied for the statue to be moved elsewhere at the Capitol, and Congress was happy to oblige. Wise argued for dumping most of the monument altogether. “The head, he said, was a good one; he would have that sawed off and placed in a suitable position,” the New York Evening Post reported, “but he would tumble the body of the statue into the Potomac.” Rep. John Quincy Adams, a Massachusetts Whig and former president, voted to move the statue “for the reason that water dripped down on it” from the roof, the Congressional Globe reported.

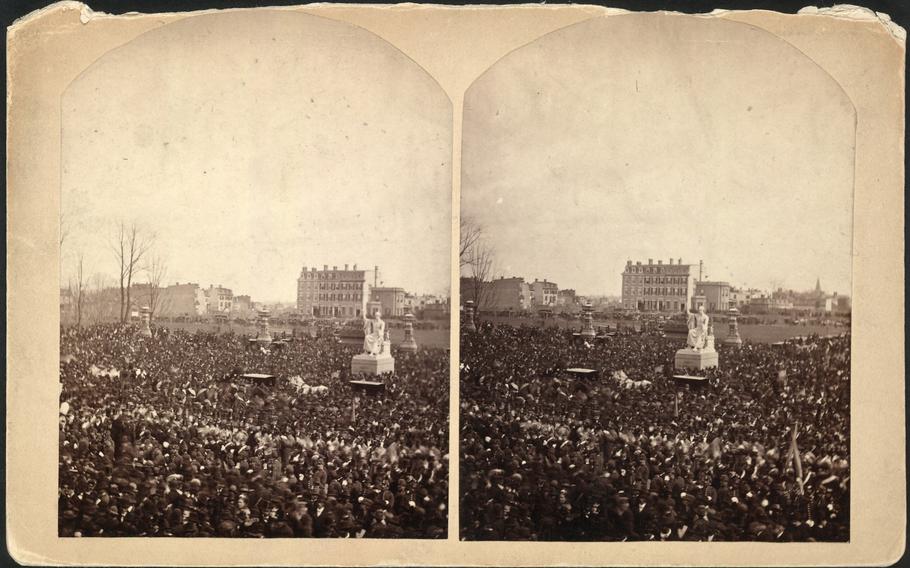

Stereo card view of the crowd at the inauguration of Rutherford B. Hayes, on the east front grounds of the U.S. Capitol, surrounding Horatio Greenough’s statue of George Washington, in 1877. (Brady’s National Portrait Gallery/Library of Congress)

In 1843, Congress had the statue moved outside to the Capitol’s East Plaza and placed on a granite pedestal engraved with the words, “First in war, first in peace and first in the hearts of his countrymen.”

The move brought the statue’s total cost to the equivalent of $1.2 million today. “Had I been ordered to make a statue for any square or similar situation at this metropolis,” Greenough complained, “I should have represented Washington on horseback and in his actual dress.”

The sculptor continued to defend his work as a symbol of liberty. While “my statue was the butt of wiseacres and witlings, I never in word, or thought, swerved from my principle,” he wrote. He predicted in time it would be judged a great work of art. He was wrong.

The statue drew even more ridicule on public display outside the Capitol. Pranksters put top hats on Washington’s head and cigars in his lips, and children playfully sat in his lap.

Meanwhile, some of the first president’s clothes were put on display in a nearby Patent Office museum. A standing joke was that if Washington’s statue could talk, the great man would say, “Here is my sword; my clothes are at the Patent Office.”

African American schoolchildren facing the Greenough statue of Washington at the U.S. Capitol, circa 1899. (Library of Congress)

In the early 1900s, The Washington Post mounted an editorial campaign urging Congress to move the statue again. The statue, The Post wrote, portrays Washington “in garb in which he could not have appeared at any stage of his career” without making people think “he had become insane and needed the restraints of a lunatic asylum.” In 1908, Congress voted to move the statue inside the “nation’s attic,” the Smithsonian Institution castle on the National Mall.

In November 1908, “George Washington, dismantled, disfigured and clad in a marble toga, and temporarily disgraced, was hauled through the streets of the National Capital today, unattended by an honorary escort save a dozen or more laborers who had taken a professional delight in driving George from the Capitol Grounds,” the Washington Times reported.

The Washington Star printed a pretend interview with Washington from Mount Vernon. “Whoever heard of a first American making such a blooming fool of himself as to sit up on a cracker barrel with a towel over one shoulder and nothing else on but a pair of things they called sandals and holding on to a toy sword with one hand?” this Washington said. “Even at Valley Forge I had more clothes than that. And I was down to my last uniform, too.”

The statue sat in a dusty corner until 1964, when it was moved to the Smithsonian’s new Natural Museum of American History, where it still got negative reviews. The New York Daily News, under the headline “It Was a Big Flop The First Time Out,” wrote: “What’s needed now is another petition to put George the Greek back in the attic.”

Today, the half-naked Washington sits on the museum’s second floor, seeming to greet visitors with a wave that says, “Toga! Toga! Toga!”

Ronald G. Shafer is the author of “Breaking News All Over Again,” a collection of his Washington Post Retropolis columns.