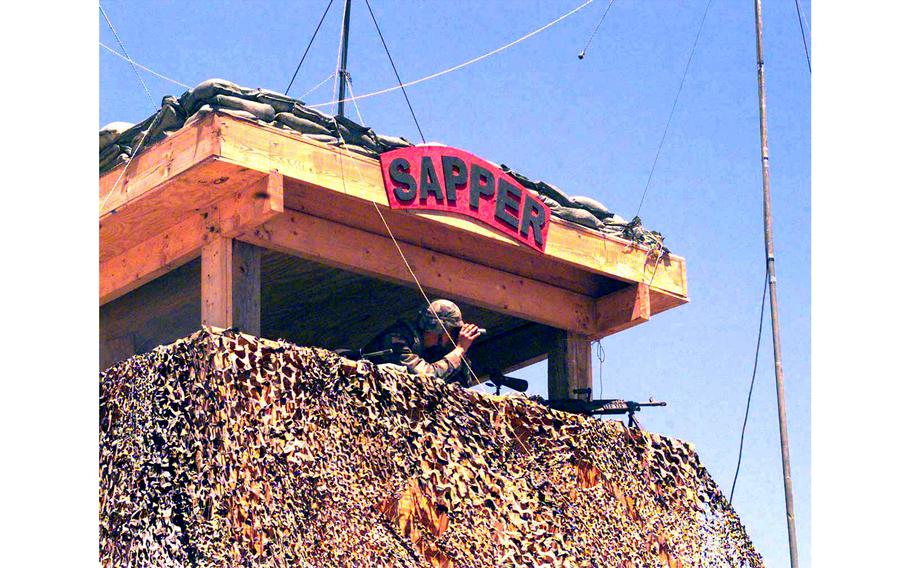

Pvt. 2 Charles Cheney, 1st Battalion, 36th Regiment, looks through his binoculars at the sector surrounding Check Point Sapper, Kosovo, July 6, 2000. (Dale Brown/Stars and Stripes)

This article first appeared in the Stars and Stripes European print edition, July 11, 2000. It is republished unedited in its original form.

OUTPOST SAPPER, Kosovo — Using the shine of the moonlight along with a mental map of the trail, a group of Army combat engineers navigates up and down a ridge, 150 meters from the Serbian border.

“We’re just trying to see if there’s any activity,” says Pfc. Jeremy Mathis before grabbing his night-vision goggles to scan the horizon.

Except for the hum of the baseball stadiumlike flood lights, it is unusually quiet at this small, tank-guarded U.S. military outpost.

It is rare that the soldiers like Mathis — of Company A, 16th Engineer Battalion, 1st Armored Division of Giessen, Germany — do not hear automatic gunfire across the border near the village of Dobrosin, where a small but growing ethnic Albanian guerilla group trains for what might be another battle with Serbian forces.

Sporadic violence in the border region the past month has renewed concerns among soldiers that the guerilla army is provoking the Serbs to fight, a situation that could draw U.S. forces into the conflict and present NATO officials with a political dilemma.

Last month, a series of bomb blasts rocked southeast Serbian towns of Buganovac and Presevo, both near the U.S.-controlled section of Kosovo. Belgrade officials blamed the explosions on “Albanian terrorists.”

Less than a week later, hundreds of ethnic Albanians fled southeast Serbia near Kosovo after police reported that the last two Serbs living in a village, an elderly father and daughter, were murdered. NATO-led peacekeepers said the ethnic Albanians feared reprisals from Serbian police and left.

Some soldiers say that the recent incidents might just be the beginning of more clashes between the Serbs and ethnic Albanians, who dominate the region south of the Kosovo border.

Ethnic Albanian guerrillas are “provoking the Serbs,” said Army Capt. Tom Hairgrove, commander of Company A.

An observation tower atop a hill offers a breathtaking view of the Serbian frontier and is an excellent vantage point for soldiers to scan the three-mile wide buffer zone between Kosovo and Serbia. U.S. soldiers heard the explosions in Buganovac and Presevo and saw a plume of smoke rise from hillside about six miles away.

They watch for similar activity constantly and keep a close eye on the armed ethnic Albanian group, known as the UCPMB — an ethnic Albanian acronym for the Liberation Army of Presevo, Medvedja and Buganovac, three predominantly Albanian towns in the valley area. The guerrilla group, which has its own insignia and uniforms, emerged in January, and has gathered strength since its inception.

The engineer battalion, which is running the outpost, estimates that between 50 and 60 guerrillas are in Dobrosin, with similar ethnic Albanian factions spread throughout the region.

U.S. soldiers, who routinely patrol the area on foot and use thermal imaging to monitor the boundary, say they often see AK-47-toting guerrilla warriors honing their fighting skills. Like clockwork, they rotate in and out of bunkers strategically dug in the areas surrounding the village.

“What has been happening — or what we believe has been happening — is that a lot of different insurgent groups have come together and just kind of picked up on the name,” Hairgrove said.

Many soldiers cross over the border into Kosovo daily, shedding their military uniforms for civilian clothes. Some are quite open about what they do, stopping to talk with the U.S. soldiers at the checkpoint. Others are more covert.

While it is illegal for them to bring their weapons into Kosovo, U.S. soldiers admit supplies and weapons for the guerrilla group probably slip through undetected. Sophisticated ground sensors help track those who attempt to cross the border by avoiding the U.S. checkpoint.

However, 1st Lt. John Huzinec, a platoon leader, said it is impossible to catch everything.

“There is a ton of stuff that gets through the border,” he said. “We just don’t have the manpower.”

While the area has been relatively quiet this past week, soldiers say there is a potential for a major showdown between Serbian forces and the UCPMB soon.

What worries U.S. officials and soldiers is that such a confrontation could spawn the type of ethnic violence that prompted NATO to intervene in Kosovo last year. They lament that the Presevo Valley could develop into a mini-Kosovo conflict, dragging peacekeepers in to diffuse it.

U.S. troops are instructed not to cross the border, but that could prove difficult if the ethnic Albanians are crushed in a battle with the Serbs or if Serbian soldiers target civilians. Should U.S. troops just sit there and watch the slaughter unfold?

“It begs some questions,” Hairgrove said. “If it’s soldier on soldier, we’re not going to get involved. Our biggest concern is about the civilian population. What do you do if something starts happening to them?”

Another scenario is if the guerrilla group enters a fire fight with the Serbs, decides they cannot win and flees the area for Kosovo. They could drop their weapons and run across the border.

That would put U.S. soldiers in the middle.

‘Unfortunately, somebody’s going to have to make the call when it happens as to what to do,” Hairgrove said.

It is a complicated, precarious situation for U.S. troops and the Pentagon and White House officials are monitoring it closely. Almost every week, a presidential aide, general or political adviser visits the area. They come to talk with troops and find out what they see and hear; what guerrilla soldiers are whispering at the border.

Soldiers are aware that their area of responsibility is under the microscope. As a small group of them sat in a bee-infested tent eating dinner last weekend, they admitted to loathing the attention. But many preferred the small outpost to a spot wedged between an ethnic Albanian town and a Serbian village because it fits closely to what soldiers are trained to do.

“This is a very politically charged debate over what we do right here,” Hairgrove said.

For now, soldiers can only watch and wait to see what will happen next.

Looking for Stars and Stripes’ coverage of the Kosovo conflict in the late 1990s? Subscribe to Stars and Stripes’ historic newspaper archive! We have digitized our 1948-1999 European and Pacific editions, as well as several of our WWII editions and made them available online through https://starsandstripes.newspaperarchive.com/