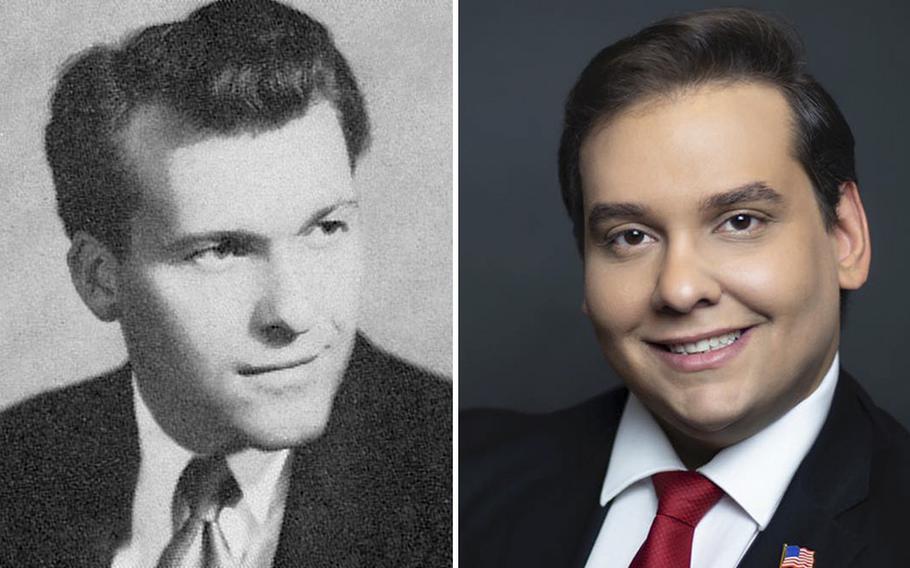

Congressmen Douglas R. Stringfellow, left and George Santos. (Wikimedia Commons and Facebook)

Douglas R. Stringfellow was the future of the Republican Party. In 1952, the GOP gained control of the House, Senate and White House for the first time in two decades, and Stringfellow was among the new arrivals. The Utahn was young (30 years old) and charismatic (a former radio DJ) and had a résumé most politicians could only dream of.

On electrifying speaking tours and at campaign events, he recounted his World War II service, for which he had been awarded a Silver Star. He had joined the OSS, the precursor to the CIA, and while behind enemy lines on a secret mission, he had captured the German physicist Otto Hahn, thus stopping the Germans from developing a nuclear bomb. He was captured by the Nazis and tortured in a concentration camp before escaping. He was the sole survivor of his OSS unit. Then, toward the end of the war, he stepped on a land mine, leaving him permanently disabled; he met his future wife, a USO performer, while recovering in a military hospital.

Only the parts about the land mine and meeting his wife turned out to be true.

Today, Rep.-elect George Santos of New York is under fire for running on a résumé that appears to be largely invented. Santos has called his lies about his educational background, professional experience and family ancestry "embellishments" and has so far resisted pressure to step down. House Republican leadership, set to gain a narrow majority in the next Congress, has been largely silent amid calls to expel Santos.

Unlike Santos's, Stringfellow's fabrications were mostly focused on one thing: his war service. And there was a kernel of truth inside his fake story. He really did enlist in the Army in 1942, and he really was grievously injured by a land mine, for which he was awarded a Purple Heart. He returned to Utah with his bride after the war, eventually gaining the ability to walk short distances with the aid of a cane. Stringfellow began telling his fake wartime story in church soon afterward, long preceding his political career.

The audience for Stringfellow's story grew and grew; soon he was going on national speaking tours. He was a terrific public speaker, and the details he shared of his spy mission were harrowing. He was forced to run over a pile of people burning to death, he said, and he watched his Nazi captors torture his friends as they tried to get him to talk. He would lift his hands to show scars at the base of his fingernails, saying they came from bamboo strips the Nazis shoved under his nails and then lit on fire.

Encouraged by local GOP party leaders to run for Congress, he gave his campaign stops a revival-like quality as he led supporters on an emotional journey through his war story. He won the open seat in a landslide.

Even after he entered Congress, his star continued to rise, culminating in a 1954 appearance on the hit television show "This Is Your Life." Each episode featured a notable guest who is surprised with people from his or her past who recount the guest's climb to success. Stringfellow's commanding officer told the audience of the congressman's heroics against the Nazis - heroics that Stringfellow said later he knew were lies.

Some of the veterans who actually had captured Hahn saw the show, according to the Salt Lake City Tribune, and did not appreciate Stringfellow's stealing their valor. Soon, journalists and Utah Democratic leaders started digging and calling Stringfellow's record into question.

At first, Stringfellow, who was running for reelection, dismissed the questions as political attacks, even going so far as to ask Republican President Dwight D. Eisenhower to release his (nonexistent) OSS records. But when the Army Times published an investigation with incontrovertible evidence of his falsehoods, the jig was up. Utah's senators and leaders in Stringfellow's church urged him to confess, and he did.

Reading from prepared remarks on live TV on Oct. 16, 1954, he told his constituents, "Somewhere along the line, the idea . . . was integrated in introductions that Doug Stringfellow was a war hero . . . Like many other persons suddenly thrust into the limelight, I rather thrived on the adulation and new-found popularity," he said, according to Time magazine. "I began to embellish my speeches with more picturesque and fanciful incidents. I fell into a trap, which in part had been laid by my own glib tongue."

When the speech was over, The Washington Post reported, "the youthful veteran cried openly."

Stringfellow's contrition only went so far; he declined to return the many awards and honors that had been bestowed on him by civic groups over the years, saying he "felt these were given me for my present abilities and activities," The Post reported. He did not resign from Congress, but when Republican Party officials found another candidate to run for his seat, he stepped aside. He moved to California and spent the rest of his life out of the public eye, dying in 1966 at the age of 44.

In 2013, Stringfellow's family found an unpublished autobiography in the congressman's belongings, which they gave to the Salt Lake Tribune. In it, Stringfellow wrote that up until a few months before he was publicly exposed, he himself had believed the story of his wartime heroics. He must have come up with the delusion while recovering in the hospital from his land mine injury, he surmised. Several psychologists specializing in PTSD told the Tribune that while extremely rare, this type of delusion was possible.

So why did he never go public with this claim? According to Stringfellow's autobiography, he would have rather been seen as a liar than as "crazy."