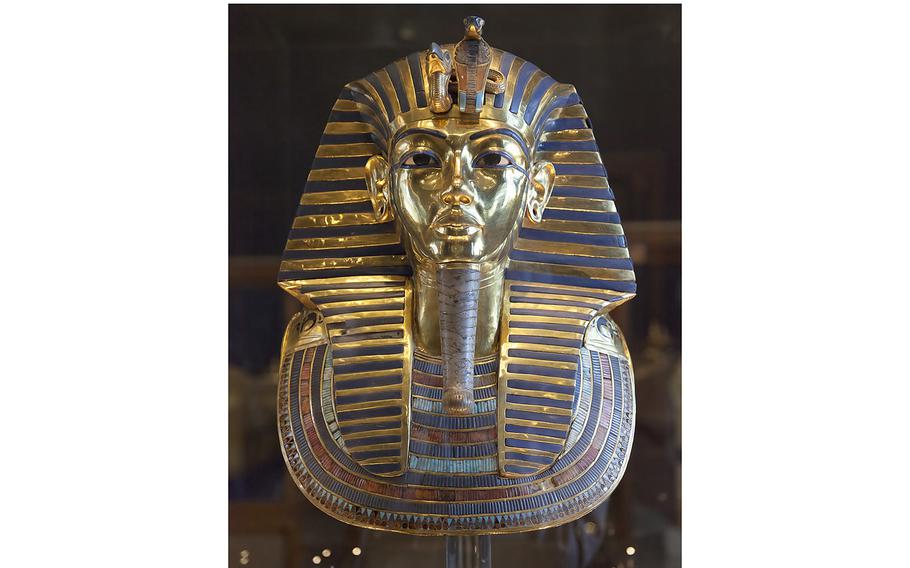

The funerary mask of Tutankhamun, 18th-dynasty Ancient Egyptian Pharaoh (WikiMedia Commons)

On Nov. 4, 1922, archaeologist Howard Carter and his team discovered the entrance to a tomb in the Valley of the Kings in Luxor, Egypt. Three weeks later, on Nov. 26, Carter smashed a hole into a stone wall in an underground hallway there. As he aimed his flashlight into the darkness, his friend and sponsor, George Herbert, the 5th Earl of Carnarvon, asked if he could see anything.

"Yes, wonderful things," he replied, according to his book "The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamen," written with Arthur Cruttenden Mace in 1923. Suddenly, the world became transfixed on a little-known pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty as gold, jewelry and other fantastic treasures saw the light of day for the first time in more than 3,000 years.

Almost as quickly, public attention shifted to the possibility of a curse plaguing all those who had entered King Tut's tomb. Sudden deaths, grievous misfortune and other inexplicable events gave rise to speculation that an evil spell was afflicting any who had dared defile the pharaoh's final resting place.

A media frenzy descended on Luxor after each calamity. Shortly after the first archaeologist death a few months following the tomb's discovery, newspaper headlines blared about the "Curse of the Pharaohs" and claimed, "Famous Spiritualist Sees Occult Reason for Fatality."

But was there really a curse? Some studies suggest a more mundane explanation: mold found on mummies and in the air at burial sites in Egypt.

Belief in a "mummy's curse" predates the Tutankhamen discovery by a century. It may have originated in England in the 1820s. In 2000, Egyptologist Dominic Montserrat reported he had discovered the first mention of it in a London "striptease" show, according to the British newspaper the Independent.

No curse was ever found written in hieroglyphics at the tomb of Tutankhamen, the Egyptian king who died at 18 or 19, around 1323 B.C. His father is thought to have been the pharaoh Akhenaten, while his mother was his father's sister, according to DNA testing. King Tut had a club foot and scoliosis, possibly caused by the tradition of incest among the royal family.

Carter himself dismissed the notion of a curse as "tommy rot." "The sentiment of the Egyptologist . . . is not one of fear, but of respect and awe . . . entirely opposed to foolish superstitions," he said, according to H.V.F. Winstone in his book "Howard Carter and the Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun."

However, Lord Carnarvon's death on April 5, 1923 — less than five months after the tomb was opened — drove rumors of a wicked spell. Newspaper accounts were rife with the possibility as more archaeologists and explorers fell ill and died. In 1926, the New York Daily News ran an article with the headline, "Vengeance of King Tut Is Seen as Death List Mounts."

Piling on was Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of the popular Sherlock Holmes stories. Upon learning of his friend's death, Doyle, a known spiritualist, told a reporter, "An evil elemental may have caused Lord Carnarvon's fatal illness."

After the earl died, others followed, including George Jay Gould, an American financier who succumbed to pneumonia shortly after visiting the tomb in 1923; Sir Archibald Douglas Reid, who perished soon after X-raying the mummy in London; and James Henry Breasted, an American archaeologist, who lived until 1935 but died of an infection following his final trip to Egypt.

In addition, the media frenzy fed off a series of unfortunate events that beset others who had visited the tomb. British archaeologist Hugh Evelyn-White, who worked on the dig at Luxor, died by suicide in 1924. He reportedly left a note in which he wrote, "I have succumbed to a curse." Carter's personal secretary, Richard Bethell, the first person to enter the tomb behind his employer, was found smothered to death at his London men's club in 1929. Some historians believe he was murdered by Aleister Crowley, an English occultist.

Carter died in 1939, a full 17 years after the discovery, of Hodgkin's disease, a type of lymphatic cancer. And yet newspapers around the world focused almost exclusively on the "Curse of the Pharaohs" when printing his obituary.

Today, science has a more rational explanation. Studies have shown that an organic source might have been a contributing factor in at least some of the deaths. Common mold — especially Aspergillus — may have been present on King Tut's mummy. The fungus is known to cause serious infections in people with weakened immune systems.

"Potentially harmful fungi survive for extreme lengths of time in tombs, and results of research indicate that such prolonged phases of dormancy can result in increased virulence," wrote English doctors Sherif El-Tawil and Tariq El-Tawil in a letter to the British medical journal the Lancet in 2003.

The death of Lord Carnarvon, who was sickly most of his life and prone to upper respiratory ailments, seems to fit the diagnosis. According to his obituary in the New York Times, he died on April 5, 1923, of pneumonia brought on by blood poisoning from a mosquito bite on his cheek that became infected after he nicked it with a razor. The El-Tawils wrote that he had likely been exposed to Aspergillus, which in turn caused the deadly streptococcus infection that killed him after he cut himself with a razor.

Spores of Aspergillus, the El-Tawils wrote, "grow especially well on grain, the supply of which was abundant in Tutankhamen's tomb, with offerings of bread and raw grains stored in numerous baskets. Lord Carnarvon could readily have inhaled contaminated grain dust as the sealed tomb was broken into."

More recent scientific studies have found two varieties of the fungi — Aspergillus niger and Aspergillus flavus — on mummies and in tombs of ancient Egypt. According to National Geographic, these strains can cause various allergic reactions, ranging from chest congestion to pulmonary hemorrhaging, or bleeding in the lungs.

That mold might have had a hand in the earl's death — or any others — is speculative. Researchers have argued for and against the idea for years. Without conclusive evidence, it will remain just a theory.

Which, of course, makes the belief in the "curse of the mummy" even more enduring.