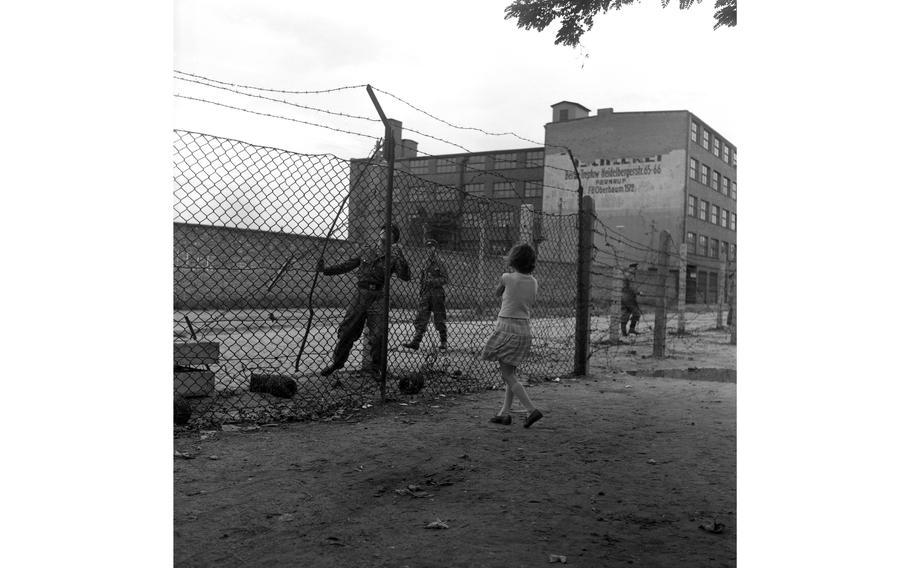

A West Berlin girl looks on as young, uniformed East Germans roll out barbed wire. (Gus Schuettler/Stars and Stripes)

This article first appeared in the Stars and Stripes Europe edition, Sept. 16, 1961. It is republished unedited in its original form. The photographs accompanying the article here were not originally published with the article, but were taken just a day before, on Sept. 15.

The barrier the East Germans are building here is an incredible work of hate. It’s more than a political dividing line — it’s a brick-and-barbed-wire wall going up along every inch of the 25-mile zigzag border between East and West.

It’s difficult for the stranger here to comprehend the barrier the East German People’s Police and Communist youth groups are putting up.

Where an invisible line divided the city before Aug. 13, there now stands a rugged physical barrier that separates neighbor from neighbor, parents from children and wives from husbands.

Where East Germans used to have free access to West Berlin, they’re now unable to cross the barrier that gets tougher to get over every day.

While houses on one side of a street belong to the West, both sidewalks and the gutter are in the East.

Buildings Going Up

Heidelbergerstrasse is a street like that. In a lower-middle class residential district, down at the end of the street a crew of workmen is putting up an apartment building.

On the street itself within whispering distance of the bricklayers, young East Germans wearing the worn and dirty gray-brown uniform of the Free German Youth (FDJ) are reinforcing a double row of barbed-wire fence.

Watching them are heavily armed and equally young greenclad members of the People’s Police (Vopos).

The two rows of barbed-wire fence are already up. Now the FDJ boys are laying a criss-cross net of barbed wire between the two fences.

They work slowly. Two carry a roll of wire on an iron bar between them, a third man lays out the wire, while a fourth secures it at alternate sides of the double fence. A fifth supervises. A vopo with a machine gun watches.

Several yards behind this team is a similar group moving along between the two fences, adding still another layer of the rusting wire to the barrier.

They all seem a little self-conscious, but they slog diligently along.

On the west side of the fence the young bricklayers take time from their work to watch.

“Watch out you don’t trip over your own barbed wire,” a bricklayer calls out. It is not said loudly or in anger. It is almost a friendly crack made by one teenager to another.

There is no comment from the East.

“After you’re finished, who’s going to roll it up again,” a bricklayer asks.

“We’ll cut your air off,” one of the barbed-wire crew says. He doesn’t speak in anger either, but rather in uncertain self-defense.

“We still have the Americans,” the Westerner answers proudly.

“But they don’t have any atom bombs, otherwise they would be testing them as we do,” the East Berliner brags.

Derisive Laughs

There are loud, derisive laughs from the construction workers.

“Where do you live?” a bricklayer asks across the barrier.

“I’m a Berliner,” the FDJ boy says with pride.

“No you’re not, you’re an East Berliner, and there’s a difference,” says the bricklayer.

No comment from the other side.

“Here any worker can buy a Volkswagen for 4,000 marks ($1,000) not the 16,000 marks ($4,000) like you have to pay,” the bricklayer says.

“Yes, but do you own one?” This from the FDJ crew.

“Come around to the back of this building and see for yourself,” says the bricklayer.

“No, we won’t go there,” comes across the barrier.

“Why not? Here you can read what you want, eat what you want, buy what you want and listen to what you want on the radio. That’s the difference between being a Berliner and an East Berliner,” comes from the bricklayer.

Vopos Listen

By now the East Berlin labor party and the Vopos are gathered to listen. They seem indifferent, but there is a large group gathered, and they’re all listening.

“How much does a worker earn in the East?” a bricklayer wants to know.

“One mark ninety an hour,” is the answer.

“We earn three marks eleven an hour,” the bricklayer says. “Why don’t you come over here?”

“No, it’s better on this side,” a Vopo declares.

“Then why are you building a fence. What’s the meaning of the fence,” the bricklayer wants to know.

There is a dead silence from the East. An embarrassingly dead silence.

It’s noon, and from the apartment building under construction comes word for lunch.

On the other side of the fence the three German youths go back to their jobs. The wall when finished will be well constructed and looks as if it’s being built to last.

Women Chat

You walk up Heidelbergerstrasse. Two women are talking across the barrier.

“… And then last night my little Hans fell and scraped his knee.”

“Is he all right?”

“Yes, he’ll be all right.”

Still farther up the street, two elderly ladies speak to each other over the barbed wire.

“I’d better ask the Vopo if you can hand it to me,” the nervous one on the East side says. She walks to the corner where a Vopo stands impassively, his submachine gun slung over his shoulder. She speaks to him. He shakes his head firmly.

The women on the east side of the barrier becomes even more nervous and moves hurriedly toward her apartment nearby.

“What did he say?” the woman on the west side asks.

“Go away. He said no.”

“Then I’ll send you the food package in the mail,” the neighbor on the west side says.

“Yes, but go away,” the other woman says as she hurries to her apartment.

Check out Stars and Stripes’ images and articles of the Wall over the decades — from its rise in 1961, to its fall in 1989 — here.

For more coverage of the Cold War, subscribe to Stars and Stripes’ historic newspaper archive! We have digitized our 1948-1999 European and Pacific editions, as well as several of our WWII editions and made them available online through http://starsandstripes.newspaperarchive.com/

To see more of photographer Gus Schuettler’s photographs, check out these other Archive Photo of the Day posts.