History

What Hurricane Andrew did to South Florida on August 24, 1992: destruction at dawn

Miami Herald August 23, 2022

On the seventh day after the storm, thunderstorms sweep through South Miami-Dade, once again drenching furniture in exposed houses and leaving many people mired in mud. This stark scene, near the Homestead city hall, shows graphically the devastation the city suffered. (Jon Kral, Miami Herald/TNS)

(Tribune News Service) — Hurricane Andrew struck South Miami-Dade on Aug. 24, 1992. This is the original account from the front page of the Miami Herald.

Hurricane Andrew, which killed at least 10 people in Dade County, knocked out power to 1.3 million households, punished South Dade and changed the very nature of the region, left a cleanup job Monday of nightmarish dimensions.

At least three others died in the Bahamas.

President Bush came to Miami for a firsthand look at a hurricane expected to cost more than Hugo.

Andrew’s eye hit shore near Florida City, 25 miles south of downtown Miami, at 4:52 a.m., descending with wind gusts up to 168 miles per hour. It roared across the state to Fort Myers and swept into the Gulf of Mexico, its next victim uncertain. A hurricane warning was posted from Pascagoula, Miss., to Vermilion Bay, La.

The killer, still whirling 140 mph winds, was expected to reach land again sometime tonight or Wednesday morning.

In Andrew’s wake here, power may be out a week or more in some sections of South Dade, the county imposed a dusk-to-dawn curfew to fight growing instances of looting and the president pledged an immediate $50 million in federal disaster aid — even before his two-hour stop in Miami.

“My heart goes out to the people of Florida,” Bush said.

By far, the worst damage was from Kendall south to Florida City.

Homestead Air Force Base was one casualty: every building was either destroyed or damaged, said Navy Cmdr. Mike Thurwanger in Washington. The base commander told his 6,500 military and 1,000 civilians workers to stay away for at least five days.

“Homestead Air Force Base no longer exists,” said Toni Riordan of the state Community Affairs Department.

Broward and Palm Beach counties suffered widespread power shortages and downed trees. The Keys escaped relatively unscathed, with the greatest damage in Key Largo.

In South Dade, Andrew tossed roofs off houses, leveled self-storage warehouses, mowed down trees and chewed up nurseries’ black ground tarps.

“It’s like an air bomb went off,” Gov. Lawton Chiles said after a helicopter tour. “Complete devastation . . . Homestead has got to be rebuilt.”

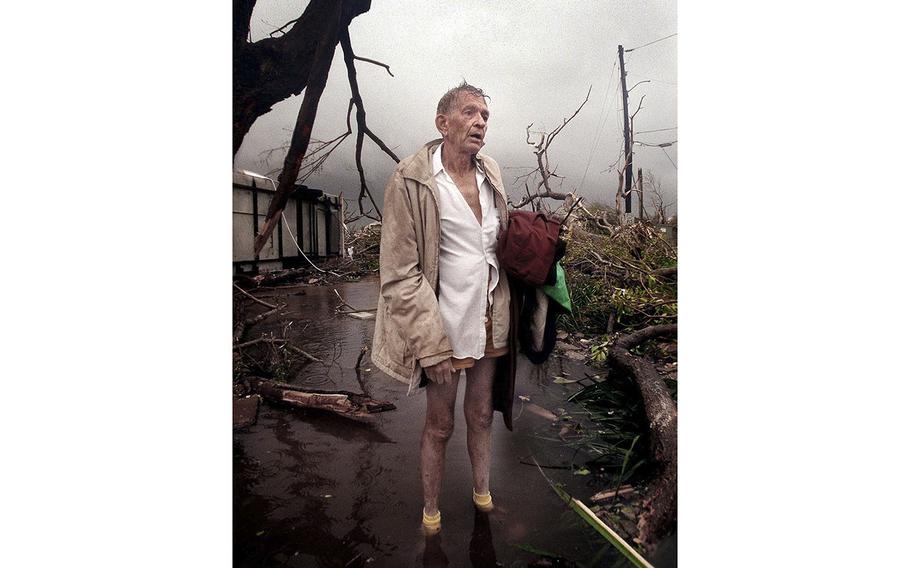

Harold “Tex” Keith stands outside his trailer park home at ground zero on Aug. 24, 1992, in Florida City after after Hurricane Andrew left the area. (C.M. Guerrero, Miami Herald/TNS)

Sen. Bob Graham, D- Fla., who took the 85-minute helicopter tour with Chiles, has toured every Florida hurricane since 1979. He called Andrew the worst he has seen: “There are going to be thousands of families with no place to live. And that’s not for a few days. That’s for a long time.”

Another measuring stick: On Monday afternoon, Metro- Dade police counted more than 50 roads blocked by fallen trees and power lines in Dade County.

Police also pinpointed four especially hard-hit areas in South Dade: Country Walk at Coral Reef Drive and 137th Avenue; Devonaire, 112th Street and 112th Avenue; the Crossings, 104th Street and 127th Avenue; and the Hammocks, Coral Reef Drive and 112th Street.

Still, as bad as it was, Andrew could have been worse.

An expected storm surge bringing a wall of water over Miami Beach and Key Biscayne never materialized. Of the one million residents ordered evacuated, nearly 700,000 obeyed, including 84,000 who stayed in four dozen shelters. And phone service remained for the vast majority.

While the South Florida death toll stood at 10 Monday night, there’s a “probability we will find others,” said Willie Alvarez, chief of Metro Fire Rescue Department. The only person identified was Jesse James, 46, of Miami, who spent the night in an abandoned truck and was hit by a tree. The other nine: seven from South Dade, one from Coral Gables and one from North Dade.

Fire-rescue received between 900 and 1,200 calls, three to four times the usual rate.

In terms of sheer wind speed, Andrew was the worst to hit Miami since 1926, said forecaster Max Mayfield at the National Hurricane Center.

Damage assessment teams were fanning out on the ground, but the best understanding of Andrew’s wrath was seen by air.

From the plane that carried Graham and Chiles, an emerging picture of destruction:

Downtown Miami, broken office windows.

Around the Biltmore Hotel in Coral Gables, splotchy roof tiles.

South Miami and Coral Gables, huge ficus trees uprooted, some shingles stripped from roofs, roofs torn.

Kendall, pool coverings ripped up, nearly every tree denuded, shingles off roofs.

Around Miami Southridge High School, whole neighborhoods affected, halves of roofs gone, rooms in homes exposed to the sky, lumber lying around like toothpicks.

Rural South Dade, nurseries shredded, trees snapped.

Naranja Lakes area, the first mobile home park decimated.

Homestead and Florida City, much in rubble, fields flooded with creamy tannish water.

The plane swung back north and hugged the coastline.

In South Dade, a business casualty: the windows were blown out on the ocean-side of Burger King’s corporate headquarters.

Bill Baggs State Park on the southern tip of Key Biscayne, the Australian pines flattened.

Marjorie Conklin cools off in a tub of water filled by a hose, surrounded by what’s left of her home and the homes of others at the Goldcoaster Mobile Home and RV park in Florida City in the wake of Hurricane Andrew’s devastation. (C.W. Griffin, Miami Herald/TNS)

Miami Beach, a noted absence of flooding.

And all along Biscayne Bay, an eerie truth of Andrew having its way: All the sea grasses are in straight lines, all leaning to the west.

What’s next?

Florida Power & Light expects power outages to last days to more than a week for sections of South Dade. Health officials issued a boil-water order for the Miami area.

County Manager Joaquin Avino Monday declared a countywide curfew from 7 p.m. to 7 a.m. The National Guard was called in to help.

Police say they hope the rule will stop looters and help emergency crews. Police spokesman Donald Blocker said anyone except emergency workers like nurses and tree cutters stopped outside after 7 p.m. will likely be arrested. Decisions about continuing the curfew will be made on a day-to-day basis.

Looters preyed on dozens of locations, but the thievery was scattered and not widespread by 9 p.m. Monday. Among the early targets: Cutler Ridge Mall, South Dade Shopping Center and the Circuit City at 19711 S. Dixie Highway. Four businesses in Little Haiti also reported looting.

Dade parks workers will spend weeks, if not months, cleaning up the debris. County Parks Director Bill Bird toured a half-dozen county parks and said “it seemed like half the damned trees were down in every park we visited. And it’s going to cost millions to clean this up.”

Many millions.

Wallace E. Stickney, administrator of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, flew to South Florida. Before he left Washington, Stickney said: “This will turn out to be one of the top three or four storms of the century.”

The storm was the same intensity as Hurricane Hugo, which left 85 people dead and $5.9 billion in damage as it swept through the Caribbean and into the Carolinas in 1989. Hugo hit largely rural areas.

Andrew, like Hugo, brought neighbors together.

On San Esteban Avenue in Coral Gables, Duffie Matson revved up his 1974 Chevy Blazer onto a street stacked with timber from uprooted black olives, jacarandas and Florida holly.

Neighbors tied a chain to the Blazer’s bumper and Matson ripped the limbs off the street and onto tree lawns. The kick- start cleanup invigorated some on the formerly tree-lined, tropical street.

“Now it’s just a tropical disaster area,” said Joe Hoyt after he used a machete to hack off the top of a fallen coconut palm. “I will cry later, I will. This place will never be the same again. Never.”

©2022 Miami Herald.

Visit miamiherald.com.

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.