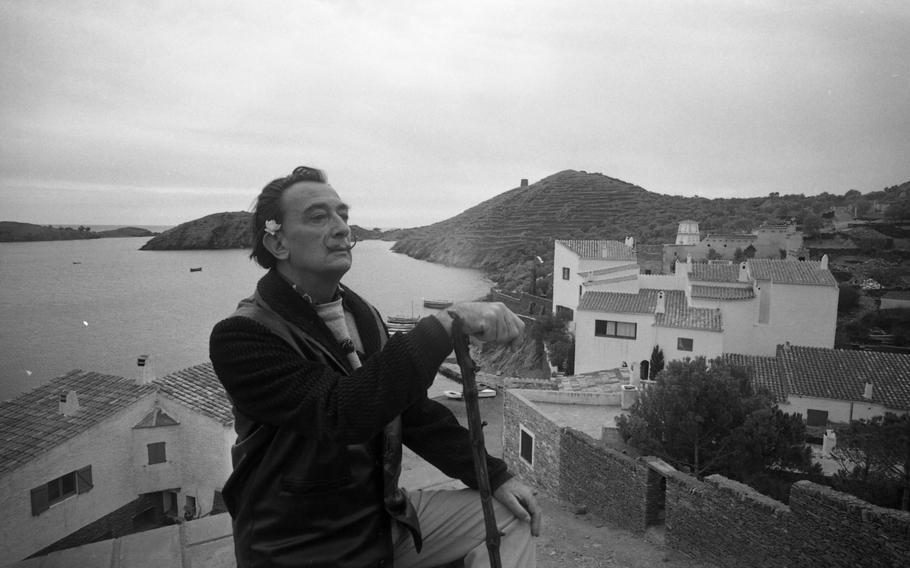

Spanish artist Salvador Dali poses on a hill overlooking his home in Port Lligat, Spain. (Gus Schuettler/Stars and Stripes)

This article first appeared in the Stars and Stripes Europe edition, Dec. 2, 1962. It is republished unedited in its original form.

Stepping inside you face a huge bear wearing a necklace of emerald-cut Jade and matching earrings, while a delicate halo of sea shell rests lightly on its head. The right paw grasps an electric torch like the Statue of Liberty. The left cradles a weird assortment of walking sticks. There's no doubt this is the home of Salvador Dali.

Getting there is considerably less than half the fun. The madcap surrealist has maintained his artistic retreat for the past 30 years at the postcard fishing village of Port Lligat, the most inaccessible spot on the Costa Brava. Only one tortuous road twists around the sharply terraced hills, braves the narrow alleys of Cadaques, and emerges at the enchanting cove.

Upon arrival, strangers are waved toward a clutch of white buildings off to the right. The cluster gives the impression that a half dozen small houses of different size were shoved together. A single small gate blocks the way, and it remains unlocked.

Once inside, you step up to a small reception room — no two rooms in the house appear on the same level — that includes a Spanish fireplace. Hanging to one side is a plucked chicken carved from wood.

Next comes the library. A picture window looks out on the peaceful inlet where Onassis and other friends drop anchor at times. A stuffed eagle and three swans stand guard over the bookcases, while a wooden arm holding a miniature American flag extends from one wall. Bunches of bright seaweed add color to the room, as artificial beetles crawl across the fireplace.

The books cover a suitable range of subjects. "Leonardo's-Drawings of the Human Body" shares space with "Secrets of the Hittites." Several volumes on Picasso have a neighbor "Noel Coward's Song Book."

Picasso and Dali have been friends for many years, but their contact has been limited to letters "since he came so mach Communist."

Then "Voila"—the 58-year-old host comes bounding into the room, his mustachios quivering "en garde." He is wearing a sweatshirt bearing a portrait of Brahms— "Today ees cloudy.- so I theenk Brahms, Brahms." Over his right ear is a small flower.

When the spirited greetings subside, the explosive artist bolts for a side door. "Allons! Vamos a ver —. zees way!" One difficulty in communicating with Dali is he shifts linguistic gears to mid-sentence without realizing it. A statement in English may get sidetracked Into French, double back into Spanish, and terminate in incomprehensible Catalan.

The door leads to an extended patio overlooking the sea. At the far end is an outdoor cooking hut made from an old wine press, drift wood, and who knows what else. Dali poses for photographs like a professional model, which of course he is, his body automatically assuming the proper angles to blend with his surroundings. No pose is too ridiculous, and he instinctively pops his eyes just before the shutter clicks.

Still another addition to the house is being added near the patio, and Dali hinted darkly this would house some of his future "inventions." "Eet was first for zee rhinoceros, but Madame Dali say no."

Dali has had a long-standing love affair with the rhinoceros — "eet ees cosmic — zee only true logarithmic curve en zee animal world" — and had supposedly made plans to add a pair of the monsters to the household menagerie.

The maestro insists that his wife is responsible for the decorations of the house — “zee personalitee of Dali ees mach too ‘violent’” — but there is no question as to how it fits in with his superb showmanship.

Returning to the house, Dali described a bullfight in his honor at nearby Cadaques. "I wanted a helicopter to take zee dead bull off to zee sky, but air force say impossible. So zey made bull zat blew up weez fireworks. Wan ball of fire hit me, but no hurt."

A group of Dali's friends in Bogota, Colombia, later heard about his frustrated plan for sending the bull to heaven and actually staged the grand exit with a chopper.

Back inside, Dali led the way (through his bathroom) to the master bedroom. On the wall behind the twin beds hung drapes of brilliant blue shaped in regal style — a crown at the top with the folds extended outward toward the floor.

Adjoining the bedroom is a dressing room with all four walls covered from floor to ceiling with photographs of Dali taken with famous people throughout the world.

Dali divides his time between his home and New York. "Port Lligat ees for leeving, New York ees for inspiration.'' He allegedly rises each day at dawn, works straight through the day except for a 15 minute siesta, and retires by 10 p.m. He maintains that he doesn't drink, doesn't smoke, and eats only "sea urchins."

Does the world's most publicity-conscious painter read what is said about him?

“Non non, I no have time. I get package each day. On good day, package ees heavee."

Is he offended when people say he is … er, eccentric?

"On zee contraree! I love crazee people of fixed qualitee."

Many people who have had close contact with Dali feel he is crazy all the way to the bank. As a leading British journalist put it, "He's not even on cloud one."

The tour was interrupted by the appearance of his Russian-born wife. Gala, who models for many of his paintings.

"Wan day I opened my door and fen in love weez her nude back," he explained. "She came to Cadaques to see zee craze painter. Wan morning I opened zee door and she was swimming in zee sea."

Madam Dali took it all with the patience of someone accustomed to an old joke and accompanied her husband to the adjoining room, surreptitiously tucking in his shirt tail.

Dali is a practicing Catholic with strong feelings on immortality. One of his recent acts was to have pieces of tissue from both himself and his wife sent to a Barcelona lab for preservation. But as every literate person in the world should know, Dali has no intention of waiting a couple hundred years for critical and financial recognition.

The next room is perhaps the most impressive in the house. Shaped somewhat like the inside of an igloo, it is so acoustically perfect that a word whispered at any point can be heard perfectly throughout the room. A magnificent custom-made divan circles the entire room, and the decorations include a rare item — a painting by Dali of his wife, her back nude.

Why are there so few Dali paintings in the house?

"Zey are mach too expensif," he explained, with just a suggestion of a twinkle in his eye.

At last the big moment arrived — the studio. But it appeared to be empty!

Dali bounded to the far corner and started cranking a hand windlass, and from the floor emerged his latest work, a massive, stunning scene some 10 by 15 feet titled "The Battle of Tetuan." The painting is based on a battle between the Moors and the Spanish in 1860 at Tetuan near Tangier. He worked on it for five months, utilizing the same technique that made his "Christopher Columbus Discovers America" so widely acclaimed. The painting was lowered into the floor so he could work on any part of it without requiring a ladder.

Many people consider Dali one of the greatest living artists. Others consider him a fraud. Most everyone will agree that he is a remarkable draftsman.

The "Battle" was not commissioned (Huntington Hartford commissioned the "Columbus" for a reported $250,000 so it could be exhibited at the new Lincoln Center in New York) and no price has been set. "Ees better — eet geeves more freedom."

The new painting has a minimum of surrealistic touches. Of course it has religious overtones, like most of Dali's work, and he included the anticipated face of his wife, twice in fact, but by and large it is a roaring drama on canvas. Like the "Columbus," it could be cut up into many smaller pictures and still have great impact, but these parts blend magnificently into a powerful panorama.

Dali was pushing to get the painting completed in time for its presentation three weeks later in Barcelona, but he still found time for certain diversions.

Picking up a canvas covered with a jumble of right angles and two small portraits, he explained, "Zeeze are ghosts doing zee tweest en zee studio of Velazquez." The idea is that you look at it while playing "twist" music and flick the lights off and on — making the figures dance on canvas.

The three weeks passed and the art lovers of Barcelona turned out en masse, along with many officials, for the presentation of the "Battle."

But true to the Spanish tradition of confusion, things were not quite ready. Drapes had to be hung at the last minute, lights had to be moved, and a convex mirror was installed in front of the painting to illustrate the incredible third dimensional impact of the work. By looking into the mirror, the figures in the painting appeared to be charging right off the canvas toward you.

Dali was dashing madly about getting everything in order, not putting on a show for the crowd. When it comes time to be serious, nobody can be more serious than Dali. Although the press was there in force, he didn't pop his eyes once during the chain lightning of flash bulbs.

Does Madame Dali always understand her husband's paintings?

"No, and I don't think he does either," she replied with a smile.

Want to read Stars and Stripes’ interviews with other artists in Europe and the Pacific? Subscribe to Stars and Stripes’ historic newspaper archive! We have digitized our 1948-1999 European and Pacific editions, as well as several of our WWII editions and made them available online through http://starsandstripes.newspaperarchive.com/