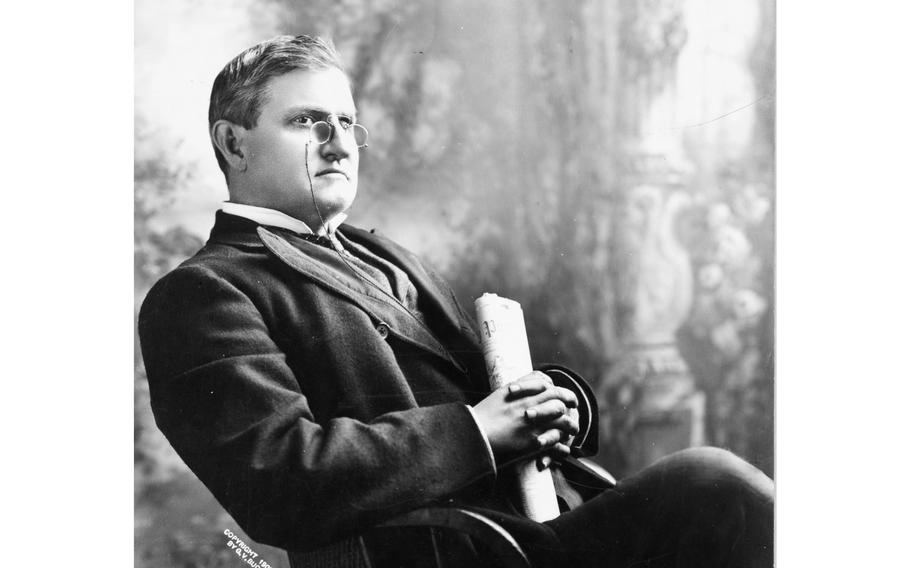

Benjamin Tillman, circa 1905. A coroner’s jury in Aiken, S.C., charged 94 white men, with murder in the Hamburg Massacre and other racial attacks in the state. None were ever prosecuted. Tillman, leader of the notorious Edgefield County Red Shirts, was one of those charged, and later became a U.S. senator from South Carolina. (Library of Congress)

On July 4, 1876, in Hamburg, South Carolina, about 40 members of the local all-Black unit of the state militia paraded down Main Street to celebrate the centennial of America's independence. At about 6 p.m., two young white men in a horse-drawn buggy rode toward the troops and demanded to pass through.

Capt. D.L. "Dock" Adams asked the white men — Henry Getzen and his brother-in-law Thomas Butler — to go around the marchers on the 150-foot-wide grassy street. Getzen refused, asserting he wouldn't move to the side "for no damned" Black people, using a slur. After a short argument, the troops stepped out of the way.

Four days later, more than 200 armed white men — many of them "Red Shirts" from paramilitary rifle clubs — arrived in Hamburg with a former Confederate general demanding that the militia unit disarm. A standoff led to an all-out bloody battle, which became known as the "Hamburg Massacre" and saw seven Black men murdered and several more wounded.

The massacre spurred additional racial violence in the South in advance of the 1876 presidential election, which ultimately led to more than 90 years of white control and segregation in the region.

Hamburg, founded in 1821 by an immigrant from its namesake in Germany, was a town of about 500 residents, most of them formerly enslaved African Americans. The town was across the Savannah River from Augusta, Ga., a city of more than 30,000 people.

Two days after the July 4 incident, Butler's father, a prominent local planter, filed charges in Hamburg against Adams for "obstructing the public highways." The town's Black magistrate, Prince Rivers, set a trial for the next Saturday, July 8. The Butlers returned with their lawyer, former Confederate general M.C. Butler (no relation), who had lost a leg in the Civil War. The former general demanded that the militia give up its weapons, but the militia refused.

M.C. Butler drove his buggy to Augusta and told some of "the boys" he "might need their assistance after awhile to disarm the negroes," The New York Times reported. That afternoon, more than 200 white men from Georgia and South Carolina gathered in Hamburg carrying pistols, rifles and shotguns. About 40 Black men, including 25 from the militia, retreated inside the town armory, a brick building near the railroad bridge from Augusta, where the white men took up positions.

At 7:30 p.m., the white men fired the first shots. "The windows were aimed at and were soon riddled with bullets," The Times reported. Militia members returned fire.

At about 8 p.m., a bullet fired by a militia trooper from the roof struck young Thomas McKie Meriwether in the head. "The ball entered the brain, and he fell dead almost without a groan. His death added to the exasperation of the whites, and it was determined to take the armory at all hazards," The Times wrote.

By dark, the militia was running short on ammunition, and many of those inside the armory began escaping. At 10 p.m., "a negro attempted to jump a fence in the rear of the building, but was seen and in an instant fell dead, his head being literally honeycombed with bullets," the Times wrote. He was James Cook, the town marshal. Another Black man, Moses Parks, was also killed trying to escape.

At about 11 p.m., Butler and other White men entered the armory and gutted the building. After finding and capturing a few men hiding there, they began breaking into houses and dragging out Black men.

"Each fugitive when found was greeted with a yell and marched to a tree, where the other prisoners had been carried," The Times reported. "The moon and the torches gleamed on bright barrels, glittering bayonets and eager and determined faces."

More than 25 men were captured. At about 2 a.m., guards surrounding the prisoners in a "dead ring" began calling out names. The first to be called was militia Lt. Allen Attaway, who "begged hard for his life," the Charleston News and Courier reported. "A volley of five or six shots was his only reply, and he fell a corpse in the road."

David Phillips "was next called and disposed of in the same way and then Albert Myniart, a ball being fired into each man," the Courier wrote. Hampton Stephens "was then called and told to run. He leaped over a low fence at the roadside as Phillips had done before and was shot before he had gone 5 paces." Nelder Parker was shot in the back and died the next day.

Pompey Curry's name also was called. "I knew what was coming, and I was running and dashed off through the high weeds at right angles," he told the Courier. He was wounded as he escaped. Finally, the Times reported, the white guards "mounted their horses and rode rapidly away, and by 3 o'clock not a sound could be heard in the village where for six hours the work of death had been going on."

Congressmen called for an investigation. Rep. Joseph Rainey, R-S.C., the first African American in the U.S. House, asked, "In the name of my race and my people, in the name of humanity and of God, I ask whether we are to be American citizens, with all the rights and immunities of such, or vassals and slaves again?"

M.C. Butler issued a statement blaming the clash in Hamburg on "the system of insulting and outraging of white people, which the negroes had adopted there for several years. Many things were done on this terrible night which of course cannot be justified, but the negroes sowed the wind and reaped the whirlwind."

On Aug. 1, Republican President Ulysses S. Grant called the Hamburg killings a "disgraceful and brutal slaughter of unoffending men." Grant ordered federal troops to South Carolina and other Southern states to protect Black citizens in the coming presidential election.

The Hamburg Massacre ignited a reign of terror against Black voters in the South. (That September, white attackers massacred as many as 100 Black people in nearby Ellenton, S.C.) Adams testified to Congress that during the battle he heard white attackers shouting, "By God! We will carry South Carolina now. About the time we kill four or five hundred men, we will scare the rest."

That November, Democrat Samuel Tilden of New York and Republican Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio were locked in the closest presidential election in U.S. history. South Carolina, Louisiana and Florida — all of which experienced violent intimidation of Black voters — filed competing slates of electors. An electoral commission gave the election to Hayes by one electoral vote. In a compromise with Democrats, Hayes soon withdrew federal troops from the South, opening the door to the return of white power and racial suppression that continued into the late 1960s.

A coroner's jury in Aiken, S.C., charged 94 white men with murder in the Hamburg Massacre and other racial attacks in the state. None were ever prosecuted. Two of those charged were M.C. Butler and Benjamin "Pitchfork Ben" Tillman, leader of the notorious Edgefield County Red Shirts. Butler and Tillman later became U.S. senators from South Carolina.

Hamburg no longer exists. A historical marker near the battle site calls the massacre "one of the most notable incidents of racial and political violence in South Carolina during Reconstruction." History shows the Hamburg Massacre, sparked on the day Americans celebrated 100 years of freedom, helped kick off an escalation of racial violence during an election that ultimately led to the destruction of the freedom and rights of Black Americans in the South for nearly another century.