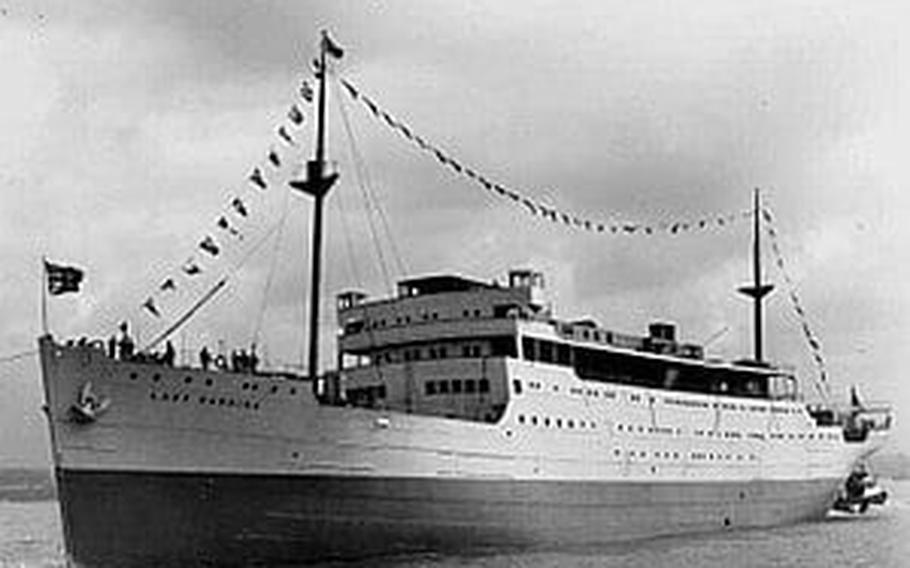

The Lady Hawkins was torpedoed by a German U-boat submarine in 1942, and its location remains unknown, despite the availability of high-tech search and seafloor mapping equipment. (Facebook)

(Tribune News Service) — The Graveyard of the Atlantic holds many secrets, but few have a story as haunting as the sinking of the Lady Hawkins — a Canadian “luxury liner” that disappeared off the North Carolina coast with about 250 people.

It happened 80 years ago this month, and the mystery is not how the ship sank — but where.

The Lady Hawkins was torpedoed by a German U-boat submarine in 1942, and its location remains unknown, despite the availability of high-tech search and seafloor mapping equipment.

It’s as if an entire cruise ship — and two lifeboats full of people — simply vanished.

Finding the wreck is a fantasy shared by war historians in both the United States and Canada, but maritime researchers say there is a good reason no one has ever gone looking for the Lady Hawkins.

And it has a lot to do with what happened that January morning in 1942, when one calamity after another befell the passengers and crew.

The Lady Hawkins’ demise

Only 71 of the 322 people aboard the Lady Hawkins survived the sinking, Uboat.net reports. Some counts put the death toll as high as 258.

The ship was unescorted and highly vulnerable when it encountered a German U-boat 150 miles offshore, somewhere between Cape Hatteras and Bermuda, historians say.

At 7:43 a.m. on Jan. 19, 1942, the U-66 surfaced just over 100 yards away and fired the first torpedo, which damaged “three of her six lifeboats,” according to Civilians and Wars at Sea.

“The Lady Hawkins shuddered under the impact. ... Her forward mast crashed,” Time magazine reported. “Over on her side careened the 7,988-ton liner. Passengers and crew tumbled into the sea. A second torpedo exploded in the Lady Hawkins’ engine room.

“One lifeboat got away,” the outlet reported. “Somehow 76 people, some in night clothes, hair matted with oil, managed to scramble into it or were pulled up from the sea. It was built to carry only 63. Jammed in so tightly that they could not sit down.”

Two other lifeboats also managed to launch, but the boats and their occupants were never found, according to Civilians and Wars at Sea.

Historians credit the survival of the people in the third lifeboat to one of its occupants — Chief Officer Percy Kelly, who took control and set a course. Kelly later received the Lloyd’s War Medal for Bravery at Sea for his role in their survival.

The leaking boat drifted five days before being found, with its survivors brought to Puerto Rico, the Canadian War Museum reports. Five people died of exposure over the five days.

“The sinking of the RMS Lady Hawkins represents the single biggest loss of life of any vessel off North Carolina during the Battle of the Atlantic, a fact more significant considering that a large majority of those lost were civilians,” according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Why can’t it be found?

The Lady Hawkins is an historically important shipwreck but it will likely never be found, according to marine researcher William S. Sassorossi, who is currently working with Monitor National Marine Sanctuary off the Outer Banks.

That’s not to say some seafloor explorer might not spot it by accident, experts say, but there are too many challenges to chart an expedition to go looking for it.

The biggest of the challenges is figuring out where to start, Sassorossi says.

“There are conflicting distances in the historical record, with the sinking anywhere between 150 and 180 miles offshore of Cape Hatteras,” he says.

“At that distance, it puts the wreck off the continental shelf most likely and in really deep water. Probably a couple thousand feet at least.”

Even if experts pinpoint where the Lady Hawkins was attacked, other factors come into play.

Did it sink immediately or did it drift? If it floated, where did the winds and current carry it? Did it sink as a whole, or did it go down in pieces, spread out over a larger area?

Some newspapers report the Lady Hawkins stayed afloat — and burning — as long as 30 minutes after the torpedoes struck. Others put its final minutes at closer to 20, Legion Magazine reports.

The difference could mean a matter of miles in open ocean.

“Synthesizing all these variables to create a search area is one of the biggest challenges. And then, you have to deal with actually being out on the water,” Sassorossi says.

NOAA is currently working to expand Monitor National Marine Sanctuary, which is centered around the famous wreck of the USS Monitor off North Carolina. It’s hoped the expansion will help protect other nearby shipwrecks linked to the Civil War, World War I and World War II.

However, the Lady Hawkins is not likely within the boundaries of the area under consideration.

With that in mind, not finding the ship is the next best thing to keeping it safe, experts say.

“We believe that the best way to preserve a wreck site is to leave it alone,” Sassorossi says.

Why is it forgotten?

The tragedy of the Lady Hawkins has been largely forgotten over the past 80 years, and Canadian historians say that is partly because it was overshadowed in Canada and the U.S. by more U-boat attacks along the East Coast.

“The sinking of the Lady Hawkins was also taking place against a backdrop of ... Germany’s declaration of war on the US in December 1941, as well as amid Japan’s early military successes in the Pacific and Southeast Asia, and Axis successes elsewhere,” according to Dr. Jeff Noakes, World War II historian with the Canadian War Museum.

“News of the loss of Lady Hawkins appears in newspapers alongside updates about fighting in the Philippines, or in Malaya, and the lead-up to the Japanese capture of Singapore,” Noakes says. “And for the general public, those events would often have wound up overshadowing the sinking of the Lady Hawkins, unless they were somehow connected to the ship, its crew, or its passengers.”

Americans were among those lost on the ship, he says, including people from St. Joseph, Mo., who were “on their way to U.S. defense construction projects in the Caribbean.”

“I’m not aware of any expedition to locate the Lady Hawkins,” Noakes says.

“I think it would be interesting if the wreck was found, partly because it could tell us more about the sinking of the ship,” he adds, “but also because it would help generate public interest in this story that affected people in Canada, the West Indies, the United States and elsewhere.”

©2022 The Charlotte Observer.

Visit charlotteobserver.com.

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.