The USS Maryland floats beside the capsized USS Oklahoma, Dec. 7, 1941, as the USS West Virginia burns in the background following Japan's surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. (U.S. National Archives)

(Tribune News Service) — Charles Collins thought he’d do a little Christmas shopping on Dec. 7, 1941. It was a Sunday, and he’d already filed the next installment of “A Line ‘O’ Type Or Two,” a venerable Chicago Tribune column peppered with readers’ verses and quips.

No sooner did he step outside than he heard a newspaper hawker yell: “They’re historic, and will be worth money years from now.” Headlines announced that Japan had attacked Pearl Harbor.

The previous Friday’s column, the stunned Collins remembered, had included a sympathy note for Japan’s war dead — referring to casualties of Japan’s war in China. But the reader’s jingle had been re-contextualized by the 2,390 Americans killed by Japanese aircraft that brought the United States into World War II.

Tuesday is the 80th anniversary of the day that those who were alive when it happened could never forget.

The news about the attack on Pearl Harbor spread throughout Chicago jerkily, like runaway frames of movie film.

The attack occurred at 7:55 a.m. Hawaiian time. It was shortly before noon at Comiskey Park, where fans were desperately looking for tickets to a sold-out game between the Bears and the Cardinals, Chicago’s other football team.

At 1:50 p.m., WGN broke into its coverage of the game to announce Japan’s strike on the U.S. Navy’s Pacific Fleet. But portable radios were bulky and mobile phones didn’t exist, so those in the ballpark weren’t aware of what was going on.

Listeners at home heard the news as radio stations broadcast an account phoned in by a reporter on the scene:

“Hello, NBC. Hello, NBC. This is KTU in Honolulu, Hawaii. I am speaking from the roof of the Advertiser Publishing Company Building. We have witnessed this morning the distant view of a brief full battle of Pearl Harbor and the severe bombing of Pearl Harbor by enemy planes, undoubtedly Japanese. The city of Honolulu has also been attacked and considerable damage done. … It is no joke. It is a real war.”

Reporters encountered various responses to those developments. A few Chicago streets were littered with the shattered windows of Japanese restaurants.

A Chicago Tribune reporter wrote this account:

“‘We’ll whip ‘em in two weeks,’ prophesied a Notre Dame junior over a glass of beer at Clark and Randolph. ‘Don’t be silly,’ said the man on the next stool. ‘They’ve been fighting: we haven’t. We’ll whip ‘em, but it’ll take a few months to do it.’”

“‘Finally it’s here,’ one man was heard to say.”

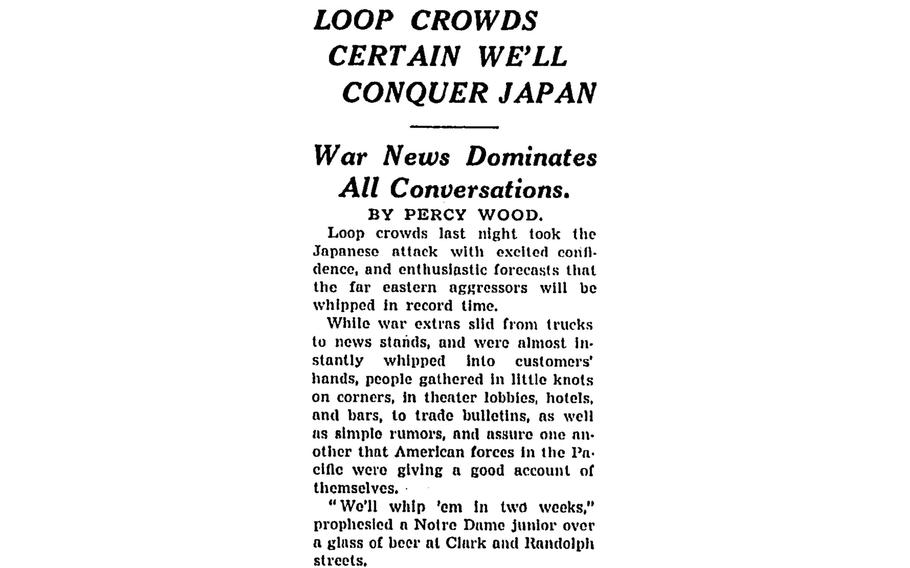

Crowds in Chicago’s Loop took the news of Pearl Harbor with excited confidence, reported the Tribune on Dec. 8, 1941. (Chicago Tribune/TNS)

For months, war clouds had hung over the U.S., but the attack still took Americans by surprise. On Dec. 7, the pastor of a Kenosha church was scheduled to speak to the Evanston chapter of the America First Committee. Having served in World War I, the Rev. Fred Franklin wanted the U.S. to stay out of a contemporary conflict.

World War I had been touted as a war to make the world safe for democracy. But in its aftermath, dictators took over Germany, Italy, the Soviet Union and several smaller European nations.

So both the America First isolationists and those who reluctantly accepted the necessity of war were focusing on battlefields far from Pearl Harbor.

“The Japanese people are in no condition to continue the wars they have already started to say nothing of taking on an opponent like America,” said Herald Fry, who covered Japan for The Christian Century, a Protestant magazine. “Old buildings are being pulled down just to get the nails.”

Even as Japan was attacking Hawaii, the Chicago Tribune was promoting it as a sunshine getaway: “And don’t forget that you’re under the protection of the American flag at all times while there.”

What troubled the Tribune just prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor was the European situation. Three days before, Dec. 4, 1941, its headline screamed: “F.D.R.’s War Plans!” The story claimed the paper had documentary evidence of President Franklin Roosevelt’s intention to deploy 5 million soldiers and sailors against the Nazis by 1943. Events proved those numbers a reasonable estimate.

Since attacking Poland in 1939, Adolf Hitler had conquered most of Europe. By late 1941, only England and the Soviet Union were still resisting the German dictator.

The U.S. was giving material support to the British and Russians, and Roosevelt was under pressure to do more, but hesitated. “America should not assume the role of European policeman,” a Tribune editorial proclaimed.

Finally, Hitler cast the die.

“Things are different now,” Pvt. John Landers, an Army deserter, had said to a Tribune reporter when he walked into the Warren Street police station after Pearl Harbor was attacked. “Now I want to go back and do my part.”

Lots of Americans had a similar impulse when Germany declared war on the United States four days later.

“The period of democratic debate on entering the war is over,” the America First Committee wrote. “The time for military action is here.”

Col. Robert McCormick, the Tribune’s publisher, abandoned the America First’s position. Drawing on his service in the World War I, he counseled Americans on what to expect in the new war:

“Bear this in mind: Battle is terrible; the enemy is trying to kill you with every horrible weapon he has,” McCormick said in his weekly talk over WGN radio. “To stand up to the strain you must be as brave as he; you must be as well armed as he; and you must feel that you are a better fighting man than he.”

Casualty reports and an occasional bit of good news underscored McCormick’s message that it would be a long, bitterly fought war, with defeats preceding victories.

Midwest families and communities learned news of a more personal nature over the next few days.

Cpt. Thomas L. Kirkpatrick, a Navy chaplain killed at Pearl Harbor, had been the assistant pastor of the Oak Park Presbyterian Church.

Francis Campbell Jr.’s parents in Chicago received a two-word cablegram from their son, a Marine stationed on Midway Island: “OK, Love.” The Japanese had attacked it and Pearl Harbor simultaneously.

Pvt. Robert Shattuck was killed in the Dec. 7 Japanese attack on Hickam Field in Hawaii. His father, a druggist and the village president of Blue River, Wisconsin, had served in the 54th Infantry during World War I.

In Bristol, Indiana, neighbors weren’t surprised when the Army praised Lt. Louis Sanders for “spectacular feats of heroism” during dogfights over Pearl Harbor. Back home, he was known for daredevil stunt-flying.

“Oh boy am I proud!” his father told the Tribune. “Guess I don’t have to worry any more.”

©2021 Chicago Tribune.

Visit chicagotribune.com.

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.