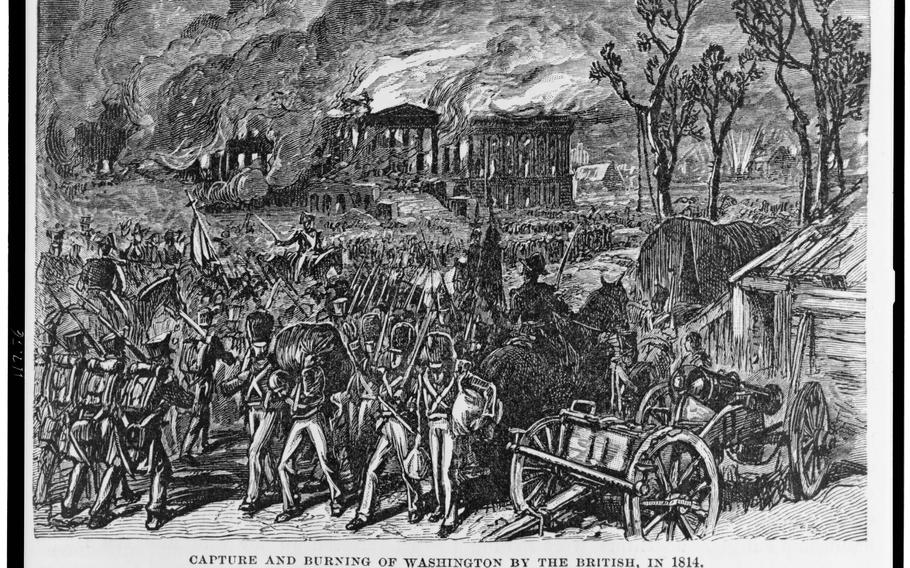

TThe capture and burning of Washington on Aug. 24, 1814, during the War of 1812. This is a wood engraving published in 1876. The depiction is not accurate because the Capitol had no center building in 1814. (Library of Congress)

On Sept. 23, 1814, Rep. Richard Mentor Johnson of Kentucky, "covered with wounds and resting on crutches," rose to propose a special House committee to investigate the attack on the U.S. Capitol by the British, according to an 1849 account by a colleague, Rep. Charles Ingersoll of Pennsylvania.

The 33-year-old Johnson, a military hero in the ongoing War of 1812, sought an inquiry into the federal government's failure to prevent the burning of the Capitol and other Washington buildings by British troops on Aug. 24 and 25, 1814 — just as a select House committee now is probing the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol by backers of former president Donald Trump. That committee has issued subpoenas to top Trump administration officials to testify and said it will seek to hold those who refuse to comply in criminal contempt.

If history is any guide, accountability is far from ensured.

The 1814 investigation began with promise. The House, temporarily meeting at Blodgett's Hotel in Washington, approved a special committee of three Federalists and three Democratic-Republicans, with Johnson as chairman. (Johnson would later become vice president under Martin Van Buren and attract controversy for his relationship with his common-law wife, Julia Chinn, an enslaved African American at his Kentucky plantation.)

The House gave the committee "the power to send for persons and papers." The panel gathered written statements from more than two dozen people, plus scores of documents.

President James Madison was exempted out of deference to his office. The highest-ranking official to testify was the secretary of state and future president, James Monroe.

Cabinet and military officials said that on July 1, 1814, Madison had ordered military preparations for a possible attack on Washington, then a modest town of about 8,000 people. Secretary of War John Armstrong Jr. insisted Baltimore would be the more likely target. Armstrong, one general told the committee, treated "with indifference if not with levity, the idea of an attack by the enemy" on the capital.

On Aug. 19, British ships moored on the Patuxent River in Southern Maryland. Intelligence reports showed British troops were heading to Washington via Bladensburg, Md., about six miles northeast of the Capitol. Gen. William Henry Winder, who headed Washington's defense, said he sent "the whole" of his troops out of the capital to meet the enemy. Most were militia volunteers from the District of Columbia and three neighboring states.

Winder said Maryland and Pennsylvania failed to provide the promised number of militia soldiers. Virginia's militia, he said, didn't reach the battlefield in time after being delayed getting arms and ammunition by a bureaucratic Army clerk who demanded signed receipts for every item. The committee report termed the mustering of forces "a great and manifest failure."

On the morning of Aug. 24, the 63-year-old Madison rode his horse to Bladensburg. Joining him were Monroe, Armstrong and Attorney General Richard Rush. William Simmons, a Bladensburg resident, later told the committee he had been scouting the area when by chance he ran into the president and the three Cabinet members as they were about to ride into the town.

Simmons said when he warned them the British were already there, Madison "exclaimed with surprise, 'The enemy in Bladensburg!' and at the same moment they all turned their horses and rode towards our troops with considerable speed." Madison moved to the back of the U.S. forces and observed the start of the Battle of Bladensburg just after noon, before riding back to Washington.

The British troops soon sent Winder's raw forces into a chaotic retreat. Winder told the committee he directed some retreating troops to rally at the Capitol, but "when I arrived at the Capitol, I found not a man had passed that way."

Winder stated that after Monroe and Armstrong rode up, the three men agreed that rather than have the "reduced and exhausted" troops defend the Capitol, it would be more strategic to send them to the heights overlooking Georgetown. The D.C. militia's general strongly disagreed. "It is impossible to do justice to the anguish evinced by the troops" on receiving the order to move on, he told the committee.

The Capitol was left undefended when British forces arrived that evening. British Adm. George Cockburn ordered his men to fire musket volleys into the Capitol, which was unoccupied because Congress wasn't in session.

Then troops rushed in and began ransacking the building. "They are in possession of the very Capitol, rioting and reveling in the sacred halls of American legislation, without fear or without danger," the United States Gazette reported.

Ingersoll wrote later that Cockburn, "in a strain of coarse levity," was rumored to have sat in the House Speaker's chair and put the question to his troops, "Shall this harbor of Yankee democracy be burned? All for it will say aye." The question "carried unanimously." The troops piled up furniture, and Cockburn set it ablaze.

The British moved on to set fire to the empty president's mansion, which would later become widely known as the White House, and the Treasury building. The next morning, troops burned the War and State departments' building. After a tornado-like storm swept through Washington that day, the British headed back to their ships.

Even before the House investigation began, critics were pointing fingers. "Oh! But for a scapegoat," one newspaper said.

Armstrong resigned as secretary of war under pressure from Madison, who moved Monroe to the post. Winder was a top target. The record is clear that "the general is unfit for any important command and that to him, principally, the Enemy is indebted for his success that day," wrote the Baltimore American.

Rep. Zebulon Shipherd, a Federalist from New York, charged that "the Chief Magistrate in particular is responsible for this shameful transaction. He, his Secretary of War were on the field of battle, or rather of flight. Was it then by their orders or the order of either of them, that the metropolis was cowardly given up to be sacked by the enemy?"

Some critics accused sympathizers of the British in Washington of privately supporting the attackers. "The British faction, the Tories, the moral traitors, what are they doing?" asked the United States Gazette.

The committee completed its investigation in just over two months, delivering a 370-page report to the House on Nov. 29. To the surprise of many observers, the report avoided any conclusions or blame. Johnson "said the committee had reported all the material facts — but had left the House and the country to decide upon the whole matter," the Hartford Courant reported.

Rep. Daniel Webster, a Federalist from New Hampshire, objected that rather than "clearing up the causes of the failure of our arms at this place," the voluminous report "was calculated (though not intended) to cover up ... what he considered to be a most disgraceful transaction," the Courant said, and "served in no degree to lead the public sentiment in respect to this disaster."

On Feb. 4, 1815, the House voted unanimously to table the report indefinitely. Then came news that Gen. Andrew Jackson had defeated the British at New Orleans, followed by mail receipt of a previously signed peace treaty, the Treaty of Ghent, ending the war.

Congress never voted on the report on the burning of the Capitol. Lawmakers shied away from "implicating so many marked personages," Ingersoll wrote in 1849. "The fall of Washington was put to rest as one of those overwhelming and incurable evils which cannot be redressed, explained or dwelt upon, but must be consigned to contemptuous amnesty or merciful oblivion."