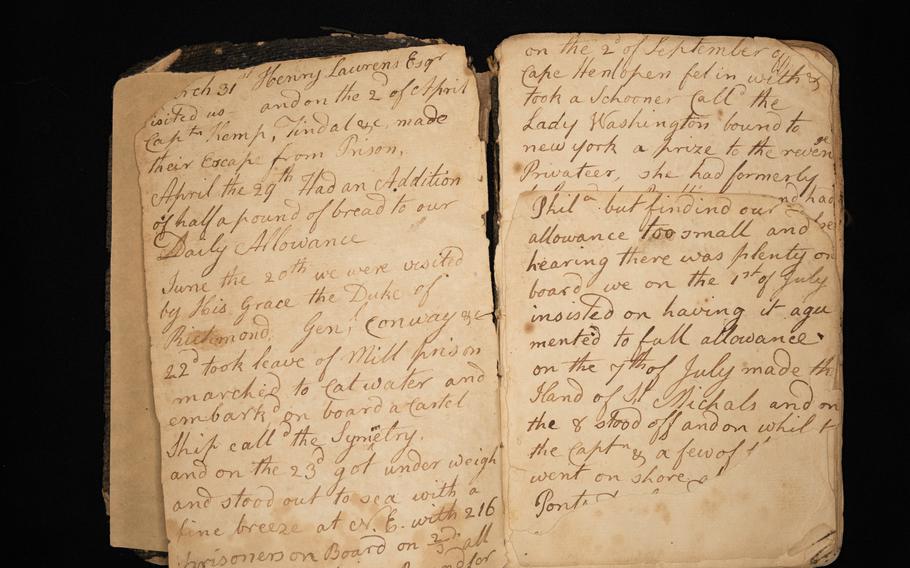

An image of the diary of John Claypoole, third husband of Betsy Ross. (David Edge)

It began with an unmarked, unremarkable box tucked in a corner of a garage in California. Inside, under miscellaneous letters and old high school yearbooks, was a smaller shoe box. Inside that, under old coins and a numismatist pamphlet, lay the 240-year-old diary of sailor John Claypoole, a Revolutionary War prisoner of war and later the third husband of the flagmaker known as Betsy Ross.

"It was wrapped in a piece of paper that said, 'John Claypoole diary to be handled with great care,' which was sort of funny we found it in a paper shoe box in a box in this garage," recalled Aileen Edge, who with her husband uncovered the priceless item in her mother's Marin County home in June 2020.

In the journal, Claypoole describes his capture by the British while a privateer at sea, being charged with high treason for "being found in arms and in open rebellion" against the king, and his time at Old Mill Prison near Plymouth. He wrote about the hardships of life in captivity; about another inmate's escape attempt that ended with the man being shot; about watching, in March 1782, as "M. Joseph Ashburn departed this life after an illness of about a week which he bore with amazing fortitude & resignation."

At the time of his death, Joseph Ashburn was married to Betsy Ross. Her first husband, John Ross, had also died during the war.

The diary predates Claypoole’s relationship with Ross, so she is not mentioned in it. But the document, and a Claypoole family Bible found around the same time, gives perspective to Ross’ place in the nation’s founding, said Philip Mead, chief historian and curator at Philadelphia’s Museum of the American Revolution, which put both items on exhibit during the July Fourth weekend. While a transcription of Claypoole’s diary has existed for years, this is proof that what it contained is correct.

"This really taps into the profound sacrifices she and her family made to create the United States. Whether she created the first flag or not, she certainly helped create the country," Mead said. "It's crucial to have the original documents because they are the only unimpeachable sources. It wasn't that we didn't know about these great sacrifices, but this confirms it."

Two entries in the Claypoole Bible, which has never been documented before, further emphasize the family's commitment to the American experiment. The first notes the Ross-Claypoole union: "John Claypoole and Elizabeth were married the 8th day of May in the year of our Lord 1783 and in the 8th year of Independence of the United States of America."

The second entry records the birth of a son to John Claypoole's sister: "Alexander Trimble son of James and Clarissa Sidney Trimble Born the 20th of March 1783, 12 minutes before ten o'clock PM (being the day that Hostilities ceased between the United States of America and Great Britain, after a long and cruel war.)"

"The fact that they give Christian year and the years since independence shows how sacred the country had become to them through their many sacrifices," Mead said. "Betsy Ross herself didn't leave much in the way of personal testimony so we have to get at her thinking by reading the words of people close to her or learning about her business from the surviving invoices or accounts."

It's not written in the diary — which only covers Claypoole's time as a POW — but historians generally believe that Ashburn spoke often of his wife and at his death asked Claypoole to deliver her a message. Thus when Claypoole was back in Philadelphia, one of the first things he did was visit Ross. They married eight months later and remained so for more than 30 years.

Growing up in Marin County, Calif., Aileen Edge always knew she was a direct descendant of John Claypoole and Betsy Ross, who was formally known as Elizabeth Griscom Ross Ashburn Claypoole when she died in 1836 at age 84.

Edge's mother, Claire Canby Keleher, was the famous flagmaker's great-great-great-granddaughter and fiercely proud of her family's role in the nation's birth.

"I used to brag about it in school: 'I'm related to Betsy Ross,'" said Edge, 59, of Redmond, Wash. "I can totally remember sharing that with a great thrill."

Keleher taught her two children to fold a piece of fabric and, with one snip of her scissors, create a five-pointed-star, as Ross allegedly did when she persuaded George Washington that it was superior to the six-pointed star he’d wanted on the flag. She proudly displayed one of Ross’ sewing tables in their California home. She held an annual celebration of Ross’ Jan. 1 birthday with other descendants. When Edge met the man she would marry, her mother noted that it was fate: He’d been born on June 14: Flag Day.

Last year, as Keleher's health declined, Edge and her husband, Dave, began visiting more frequently. On each trip, they'd attempt to sort some of the many boxes and papers her mother kept.

"She always seemed to be the one who ended up with the family items, especially if someone passed away," Edge said.

Keleher died on July 14, 2020. Donating the book to the Museum of the American Revolution in the names of Keleher and her late brother, Wilbur Wood Canby, seemed like the natural thing to do. A sea chest belonging to John Claypoole had been given to the museum in 2019 by another branch of the family. The items, once kept together, would be reunited after more than two centuries apart.

"My brother and I talked about if one of us kept it, we'd just wrap it up and keep it safe and what's really gained by that?" Edge asked. "Our mom loved history so much, she would have wanted it to be in a museum. She was so proud to be a descendant of Betsy Ross."

Some important details of who Betsy Ross was and what she did during the American Revolution remain murky. The story that appears in elementary school books holds that in 1776, Gen. George Washington, then commander of the Continental Army, went to Ross’ shop in Philadelphia with a sketch for a new flag.

She accepted the commission but made one significant change to his design: changing the 13 six-pointed stars he'd wanted to use to five-pointed stars because they were easier for her to make.

The building where Ross reportedly lived and rented shop space when she sewed that first flag still stands today. "Betsy Ross House" is now a museum where someone dressed as Ross tells that story, while expanding it to note that Ross made musket cartridges in her upholstery shop and was nicknamed "the Little Rebel" because of her passion for patriotism.

Those who doubt the first flag story note there are no diaries, newspaper accounts or letters showing that Washington sought out Ross’ skills or that the pair knew each other. There’s no mention of Ross in founding documents. Her connection to the flag was unknown until her grandson wrote a book about the family’s story in the 1870s.

Supporters say that Ross’ grandson had no reason to lie and that he presented sworn affidavits from family members testifying they’d grown up hearing the family tale.

In 2014, curators at Washington's Mount Vernon estate found a receipt for bed furnishings paid to a Mr. Ross of Philadelphia dated 1774, proving Washington and Ross were acquainted. Betsy Ross may also have met Washington while worshiping at Christ Church after she was "read out" of her Quaker meetinghouse in part because of her support for the war.

Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, who originated the phrase "well-behaved women seldom make history," has long dismissed the first flag story, but she's excited by the information found in the Claypoole Bible and diary.

"I love the fact that the emphasis now is not on a piece of needlework or an artifact but on the person and the larger context that the American Revolution required sacrifices," she said. "What's important is seeing Betsy Ross as a symbol of the multiple ways ordinary people, male or female, white or non-white, made a difference."