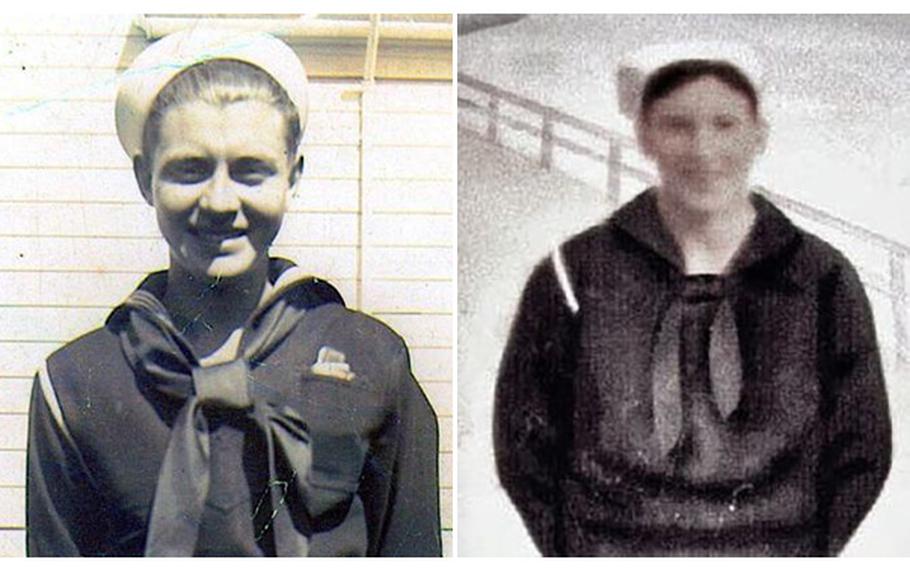

World War II Navy veterans Floyd Helton, left, and Stanley Owsley. ()

(Tribune News Service) — Floyd Helton was looking to learn a trade when he decided to join the U.S. Navy in late 1940, but he needed a parent’s permission because he was only 17.

He asked his mother, but she said no. So he turned to his father, Herbert Helton, of Pulaski County, who was divorced from his mother.

His father signed the application, and Helton formally enlisted in June 1941. Six months later, he was killed aboard the USS Oklahoma when Japanese warplanes hit the battleship with multiple torpedoes during the attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941.

His father, who died in 1996, carried some guilt the rest of his life.

“He kind of held himself responsible,” said Vicki Easley, whose mother is Floyd Helton’s half-sister. “It brought sadness and that stayed with him.”

Now, 80 years after they gave their lives for their country, Helton and another sailor from Kentucky killed aboard the Oklahoma, Stanley Owsley, are coming home.

Helton, who grew up in Somerset, and Owsley, of Paris, were among 429 USS Oklahoma sailors killed at Pearl Harbor. They weren’t recovered until 1944 when workers finally righted the ship, according to information from the Navy.

Only 35 of the men could be identified at first. Helton, 18 when he died, and Owsley were not among them, and were buried with the other unknowns in Hawaii.

The military exhumed the bodies in 1947 in an unsuccessful effort to identify them, reburied the remains in 1950 in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, and then disinterred them again in 2015 in a new push to identify the sailors.

With advances in DNA technology, the effort was much more successful. By January 2021, 300 had been identified, according to the Navy.

Owsley and Helton were identified last year, but the Navy only recently announced the findings publicly.

Owsley’s sister, Mary Ida Owsley Linville, missed him terribly, said Betty Short, one of Linville’s granddaughters.

Linville was only two years older than her brother and they were close. She donated a DNA sample to use in the identification process, but died in May 2020 at age 104 without knowing the effort had been successful.

The Navy notified Owsley’s family of the identification last fall.

“It’s kind of bittersweet that she didn’t live long enough to know they’d found him,” Short, who lives near Richmond, said of her grandmother.

Owsley wanted to make a career for himself after growing up poor on a farm in Bourbon County, Short said.

He enlisted in the Navy in May 1938 and had been promoted several times by the time of the Pearl Harbor attack, when he was an electrician’s mate 3rd class, according to information supplied by the Navy.

His sister, Linville, heard news on the radio that the Oklahoma was one of the ships hit at Pearl Harbor, knew Owsley was assigned to the ship, Short said.

His family received a telegram a few days later saying he was missing, and before the month was out received another telegram saying he was considered dead. He was 23.

“My great-grandmother said her heart would never be full again,” Short said.

Short said her grandmother always wondered whether her brother’s body had been lost in the ocean or was among the unknown sailors buried in Hawaii.

Knowing he’d been identified and being able to bring him home would have meant the world to her, Short said.

Owsley’s remains will be cremated and interred next to his sister on Aug. 5.

“My grandmother would have wanted this,” Short said. “We’re blessed that he was found. We’re proud that he served his country.”

Easley said her mother, Louise Helton Valentour, who was 10 when her brother died and is now 91, was thrilled that Helton had been identified.

Helton’s father had asked his surviving children to do whatever they could to bring him home if it ever became possible.

Floyd Helton’s half-brother, Carroll Helton first took up the responsibility. He kept paperwork about Helton and he and his son submitted DNA samples to help in the identification process.

Carroll Helton gave the paperwork he had to Easley’s mother before he died. She assumed responsibility for being the contact point with the Navy, and has been involved in the arrangements for his funeral.

“This is something she promised her daddy,” Easley said of bringing Floyd Helton’s body home. “She’s glad this is happening and that she can see this through.”

Helton will be buried July 31 next to his father at a cemetery at Sloans Valley, in southern Pulaski County.

Gov. Andy Beshear said he will order flags to be lowered to half-staff on the days of the funerals for Helton and Owsley.

“For almost 80 years, families of the sailors who died on the Oklahoma could mourn their sons and fathers, brothers and husbands only at a distance,” Beshear said in a statement.

But thanks to the persistence of the military in identifying them, Beshear said, “ Kentucky sailors are finally coming home.”

___

(c)2021 the Lexington Herald-Leader (Lexington, Ky.) Visit the Lexington Herald-Leader at www.kentucky.com Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.