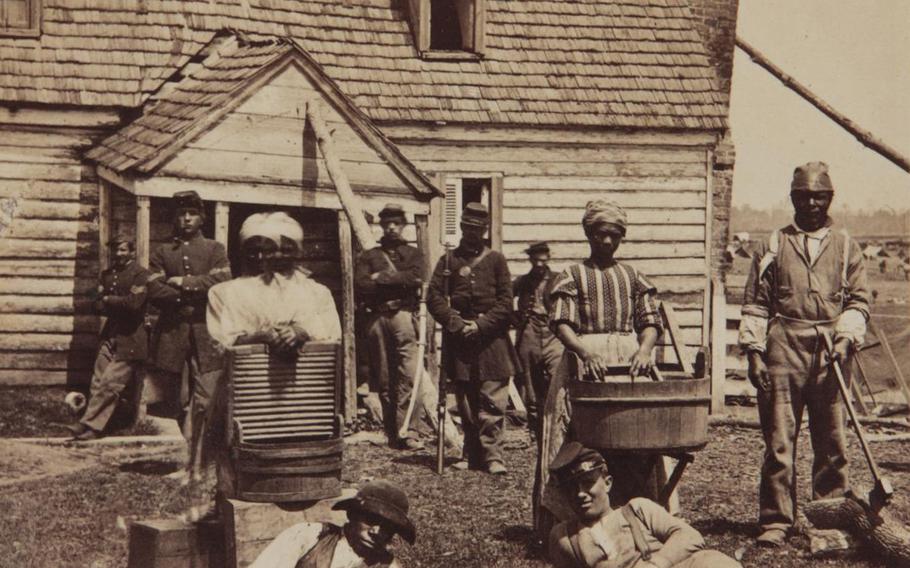

Laundresses with Union soldiers, circa 1863. (Mathew Brady/Library of Congress)

There was no one moment when freedom came to the enslaved in the United States. When President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, the clouds did not part, the sun did not shine beams of freedom, and the shackles of slavery locked for nearly 250 years did not magically fall away.

And it doesn't diminish Lincoln to acknowledge that.

"It's a pretty entrenched story in our national memory that Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, and on Jan. 1, 1863, enslaved people were free," says historian Amy Murrell Taylor. "We need to puncture a big hole in this national mythology - without diminishing Lincoln."

The truth is much more complicated. Millions of Americans gained freedom from 1861 to 1865 in a slow-moving wave that includes the Emancipation Proclamation, Juneteenth and the passage of the 13th Amendment. There are millions of stories to tell.

Many ran across Union lines and emancipated themselves, flooding into hastily constructed "contraband" camps. (Taylor calls them refugee camps.) Some brought family members and wagonloads of belongings, others were forced to choose between freedom and their children. For some, the Union line and its liberation came to them.

Some formerly enslaved people encountered sympathetic White soldiers and missionaries who helped them. Others were treated like vagrants or were handed over to be re-enslaved. Some gained freedom by enlisting in the Union Army and fighting the people who had enslaved them. Some states read the writing on the wall and abolished slavery by state action during the war; others dug in their heels and wouldn't let go until the 13th Amendment forced them to months after the war was over.

"For many people, the process went on for years," Taylor told The Washington Post. "I think we miss the actions of enslaved people, how pivotal they were in pushing emancipation forward, when we focus just on one moment." Without them, she said, the Civil War might have ended without abolition.

In Taylor's 2018 book, "Embattled Freedom: Journeys Through the Civil War's Slave Refugee Camps," she used a "treasure trove" of military records to reconstruct this period from the perspectives of individual people who forged new lives in the refugee camps that dominated the landscape but were forgotten in historical reports.

Edward Whitehurst had been "self-hired" for some time, meaning his enslaver let him lease himself to others, an arrangement that left Whitehurst with a portion of the rental fee. That wasn't out of the goodness of his enslaver's heart. That portion was supposed to cover his room and board in Newport News, Va.

Whitehurst carefully saved what he could for years, hoping one day to buy his and his wife Emma's freedom. He kept the money hidden in a trunk on the nearby plantation where she was enslaved. At age 31, he had saved about $500, worth about $16,000 today. It wasn't enough to buy their freedom yet, but he was well on his way.

Then the Civil War broke out. Their enslaver enlisted in the Confederate army and left. And though Virginia seceded from the Union, a U.S. military installation in the southeastern corner of the commonwealth never fell to Confederate forces. And it was only seven miles from them.

Within days, enslaved people began to arrive at the installation seeking freedom. Soon the man in charge, Brig. Gen. Benjamin Butler, made an unprecedented order: Since Virginians claimed to be citizens of another country, Americans were under no obligation to abide by the Fugitive Slave Act and return runaways. In fact, they were "contraband" of war, he said, and would be given protection and, where possible, jobs to help the Union effort.

Thus Fort Monroe, the place where Black people were first enslaved in the English-speaking world, became the place where hundreds ran to their freedom 250 years later, including the Whitehursts.

"I was a slave at the beginning of the war," Whitehurst later said in a sworn statement, "but I was free to all intents and purposes on the 27th day of May 1861."

Plus, he had $500. As soon as they could, the Whitehursts remarried - likely the first time in their lives they were legally recognized as people and not property. Edward made at least two risky trips to the old plantation to retrieve his savings and to harvest the crops for their own use. As things began to stabilize in the area, they set up a general store right across a creek from the fort, supplying soldiers and other formerly enslaved people with fresh meat and vegetables, eggs, ginger cakes and even lumber. It was so successful they were able hire some of their friends.

But while they no longer had enslavers, they were still vulnerable to the capricious whims of Union officials. Business suffered when many of their Black customers didn't get the pay they were promised from the U.S. Army. One official wanted the store shut down. And when Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, it specifically exempted Union-controlled parts of the Confederacy, leaving them unsure if they would stay free or be returned to slavery.

Worse, in August of 1862, as Gen. George McClellan's army retreated from the failed Peninsula campaign, the dejected soldiers ransacked the store. They loaded the entire contents of its shelves into their wagons and took off, leaving the Whitehursts penniless.

This is the reason Taylor was able to get such a detailed account of the Whitehursts' early days of freedom. In 1877, Edward Whitehurst petitioned the government to compensate him for the loss of his goods. By then he and his wife had saved up another nest egg and farmed their own land, but 15 years later he still remembered exactly what had been taken: 40 pounds of butter, six hogs, two bushels of ginger cakes, and so on. He asked for $722; he received $115.

The first time Eliza Bogan crossed over to the Union side, she wasn't seeking freedom. She was trying to get her husband, Silas Small, to come back to the cotton farm in Phillips County, Ark., where he had been enslaved.

In the fall of 1862, Union troops got hold of nearby Helena, Ark., on the Mississippi River. The commander hired escaping enslaved men, who showed up, to build a fort, promising them freedom. Small was among those men. But then the fort got a new commander, who wasn't interested in paying or feeding them and didn't mind returning escapees to their enslavers.

Bogan got word that her husband was severely ill, so she brought him back to the plantation where she lived and nursed him back to health. Jan. 1, 1863 - the day Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation, freeing enslaved people like Bogan and Small - came and went without notice.

By April, Lincoln sent a general to tour the Mississippi Valley to make it clear to the officers and soldiers in the region that they should be enforcing his proclamation. It was on this tour that the first Black soldiers were recruited for the Union army. Small was one of them, and this time Bogan followed him over the Union lines, probably leaving her seven children within grasp of their cruel enslaver.

Her husband was soon captured by Confederates and spent a short time re-enslaved before escaping again. This time, Bogan wouldn't let him out of her sight; she joined the regiment as a laundress, earning a wage and rations from the army. After a campaign through Mississippi, Small came down with the measles. She tried again to nurse him back to health, this time unsuccessfully.

Although her husband was gone, Bogan stayed with the regiment for the rest of the war. Confederates so often raided the "contraband" camps that she was probably safer with the soldiers, Taylor noted. Eventually they were sent to Texas, where they helped enforce emancipation, contributing to the celebration that became known as Juneteenth.

Bogan married again, to a man in her regiment, and they returned to Arkansas in January 1866, where they became sharecroppers. She was still alive in 1920 when, 25 miles away, more than 200 Black people were lynched in the Elaine Massacre.

From a young age, Gabriel Burdett's mother told him she had had a vision that sometime in his life, he would be freed. And not just him, all enslaved people, she told him. It was a bold prediction, given slavery's two-century history at that point.

By the 1850s, as he entered his twenties, he was a Baptist minister, probably preaching in secret meetings to other enslaved people in Garrard County, Ky. Eventually, a White Baptist church gave him permission to preach to his congregation in their building once a month. This may have looked like a kind gesture, but it also placed him under closer supervision. White observers could make sure he wasn't straying from their proslavery version of Christianity, where enslavement was sanctioned by God, and submission to a "master" would bring contentment. By June 1862, Burdett was in trouble with White church officials for something he had said during a sermon; it is unclear what.

Kentucky stayed pro-slavery and pro-Union during the Civil War, the latter somewhat tenuously. Because of that, the Union army there was not the liberating force it often was in the Confederate states.

The Emancipation Proclamation did not apply to Kentucky, and in the summer of 1863, the U.S Army forced Burdett into a wagon and carried him off to work as a slave for the Union. His wife and kids stayed behind.

At Camp Nelson, Burdett suddenly had a much bigger congregation and little supervision. And for the first time, he encountered White Christian missionaries who were antislavery. Then in the spring of 1864, the army began enlisting enslaved men in Kentucky, promising freedom if they joined. Burdett and 14,000 of his brethren signed up.

He never saw combat. He worked with the missionaries to set up schools for the Black regiments at Camp Nelson, and after the war ended, he too was sent to Texas. By 1866, he was reunited with his wife and children, and they moved to Kansas to start a new life. They were finally free.