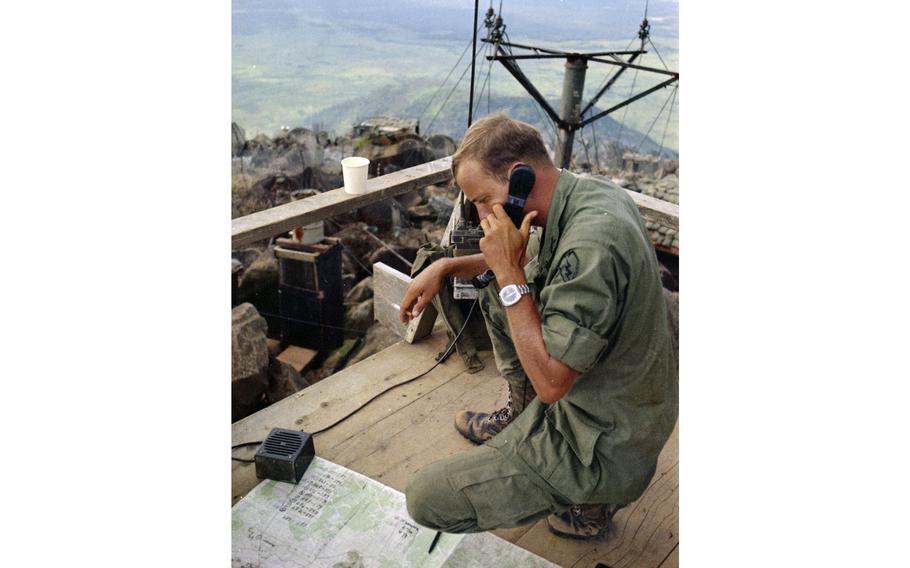

From his vantage point at the radio relay station atop 3,200-foot Nui Ba Den mountain in October, 1969, 1st Lt. John Lowe of Columbus, Ohio, an artillery officer with 3rd Battalion, 22nd Infantry, 25th Infantry Division, spends his day calling in artillery strikes on the surrounding flatlands and hills. (Joe Kamalick/Stars and Stripes)

NUI BA DEN MOUNTAIN, Vietnam — The major tourist attraction in Tay Ninh Province for the military is a small radio relay station sitting atop Nui Ba Den (Black Virgin Mountain), a solitary block of granite that juts 3,200 feet in the air above Tay Ninh.

"This is the first time in my life that I have seen a four-star general and I have seen two of them since I have been here," said 1st Sgt. Harry M. Meyers, a veteran of seven months on the mountain.

Colonels, generals, Congressmen, reporters and anyone else who can think of an excuse to visit or inspect the tiny three-acre facility flock to the top of "the rock." Since, according to Meyers, most of the major units in III Corps tactical zone have radio relays on the mountain there is no lack of excuses or visitors.

Pilgrims have long beaten a path to the top of the mountain. Before the Viet Cong took over the mountain in the early 1950s, Buddhists came regularly to worship at the altar of the Shrine of the Black Virgin. After Special Forces troops assaulted the top of the mountain and established the camp in 1964 the Viet Cong have paid frequent visits over the protests of the camp's defenders.

The altar is still there, sharing its pagoda with several tons of radio equipment.

Clouds also enjoy visiting the mountain. The camp calls it fog. Any respectable cumulus cloud (and there are more of those than you would think) will dip down for a closer inspection preventing sunlight from reaching the camp and helicopters from landing there.

The camp is supplied solely by helicopter. Mail,, food, soda, parts, fuel, barbers and visitors must all come by copter for the VC own the rest of the mountain.

There has been so much air traffic around the mountain (and several collisions) that the mountain commander, Maj. Robert Dutcher, brought in an Army air traffic controller to handle the copters and any air strikes that are held on the mountain. The controller sits in an observation capsule on top of the radar tower, which in turn sits on top of the pagoda and the pinnacle of the mountain. On top of the radar tower flies the U.S. flag.

The flag is a taunting symbol of U.S. presence on the mountain and few of the 200 members of the camp doubt that Charlie will try to remove it from the staff.

According to Dutcher, the camp now boasts every piece of defensive equipment employed in Vietnam by the Army.

Half of the camp's population are signalmen. However, during an attack, Dutcher said, everybody becomes infantrymen.

During the day when the sun is out, the camp does seem fairly impregnable. But when darkness falls, the fog rolls in, and the only thing one can see in the void beyond the bunkers is the faint glow of the perimeter lights.

The fog not only cuts visibility down to zero, but also produces the cold dampness that chills the soul of the camp.

Moisture corrodes the wiring of the camp, causing frequent electrical short circuits, and rots the wood of the bunkers. On the telephone, the next bunker sounds miles away. Wet clothes do not dry out — just mildew until thrown away. And always there is the loneliness.

Some of the men have not been off the mountain for five months. Some more fortunate ones leave at least once a month (the normal tour of duty is four months).

Dutcher, to combat the loneliness, keeps the men busy on work details — building defenses and sprucing up the camp. The men work up to 12 hours a day, excluding the four hours of guard duty they must pull.

Hot meals three times a day, the camp's small PX, television and an occasional movie leads the men to echo Spec. 4 George Whitehead's comment that the camp "beats walking in the rice paddies below."

And it is a nice place to visit — for one night.