Coronavirus

AnalysisProtests in China frustrate Xi's agenda of expanding political control

The Washington Post December 2, 2022

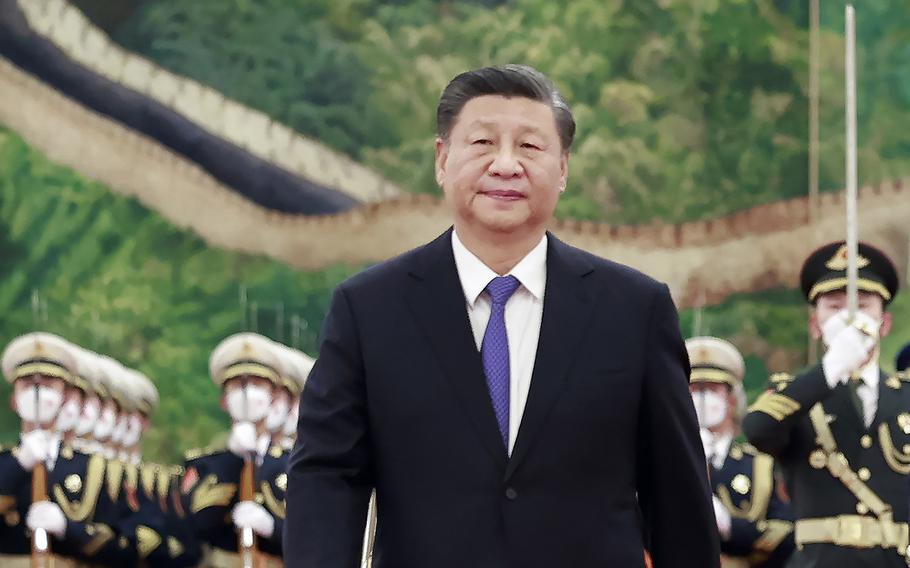

Chinese President Xi Jinping walks during a ceremony at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on Nov. 28, 2022. (Ding Lin/Xinhua News Agency)

Stars and Stripes is making stories on the coronavirus pandemic available free of charge. See more stories here. Sign up for our daily coronavirus newsletter here. Please support our journalism with a subscription.

Under a highway bridge near the embassy district of Beijing, a protest Sunday night against the country's harsh "zero covid" restrictions fell silent as a young man with a megaphone started to address the crowd.

"What everyone needs to be aware of," he began, "is that among us are anti-China foreign forces, they are nearby . . ."

The crowd immediately interrupted him. "No there isn't," some yelled. "We are all Chinese patriots," others shouted.

The groundswell of discontent that has gripped at least a dozen major Chinese cities in recent days was triggered primarily by resentment of the draconian measures the government has maintained to quickly snuff out, if not prevent, coronavirus outbreaks. But the protests in Beijing and elsewhere have also exposed many people's apprehension over President Xi Jinping's broader nationalist vision - which increasingly prioritizes stability and national security over individual freedoms.

For Xi, arguably the country's most powerful leader since Mao Zedong, the way for China to become a global superpower is for people to actively support the Communist Party, make sacrifices and stay in line for the greater good of the nation.

In that worldview, the United States and other Western powers are often demonized as trying to undermine China's rise. Nationalist commentators have responded to the recent demonstrations with well-worn arguments that claim the dissenters are organized by clandestine foreign agents.

"This is the [party's] usual tactic to divide people" and shift blame, said Yan, a former teacher in Chengdu who only gave his last name out of security concerns. He attended a vigil on Sunday to remember the 10 victims of an apartment building fire in the city of Urumqi, which local residents believe was made worse by firefighters' slow response because of pandemic restrictions. More than 1,000 people took part in the vigil, calling for freedom over coronavirus testing and chanting "give me liberty or give me death."

But the propaganda about foreign hostilities, deployed to delegitimize dissent during the 2019 Hong Kong protests, has lost persuasive power in the latest protests.

Citizens' concerns are "nationwide and transcend local, ethnic and class boundaries," said Chenchen Zhang, an assistant professor in international relations at Durham University in Britain. "People across the country have experienced first hand the frustrations and suffering caused by zero covid."

The variety of grievances voiced during the past week of protests and other spontaneous public gatherings reflects a breadth of anxiety about the government's handling of the pandemic during the past three years. A list of the demands were compiled and then circulated by a group of young Chinese - some in the country and some overseas - who run Citizens Daily CN on Instagram. The app is blocked in China, and the group, for security reasons, operates with complete anonymity, even from each other.

The list is about ensuring that appeals for "basic respect for human life and dignity" are heard, the account's operators said in written response to questions. They promoted it to prevent an "expanding chilling effect" on speaking out.

Liberals have used the moment to call for individual rights to be better protected, often using official slogans to support their argument. Because the country's leadership achieved its goal of "moderate prosperity" last year, quarantine conditions that undermine people's quality of life are "insulting to China," Qu Weiguo, a scholar at Fudan University in Shanghai, wrote on social media app WeChat.

While the dissent is unlikely to truly weaken Xi's firm grip on power, it has undermined his agenda and credibility as a policymaker.

"We don't know where he's getting his advice from or if he's getting advice. That's what's most concerning," said Mary Gallagher, director of the Center for Chinese Studies at the University of Michigan. Some people in China appear to have "lost confidence in the central government to make wise decisions," she said.

At a meeting of top Communist Party leaders in October, Xi justified extending his rule with promises to defend the nation against "dangerous storms" from an outside world intent on undermining China's "great rejuvenation." His signature approach to the pandemic was a central part of the narrative that he had provided stability for China by protecting it from those threatening external forces.

As early as January 2020, state media took the unusual step of declaring that Xi personally was commanding pandemic response. And for a time, the success of his crush-the-virus strategy was a source of national pride. China had far fewer covid cases and deaths than most nations. State media declared that it demonstrated the superiority of the Chinese political system.

The decision to shut the country off from the world has since turned hugely unpopular. The World Cup in Qatar has been a reminder that - with the exception of North Korea - China is alone in still trying to stop the coronavirus from circulating in the general population. During matches in the past several days, Chinese state broadcaster CCTV has been cutting away from close-up shots of maskless fans in packed stadiums so that viewers at home are not reminded of how much an outlier their country is.

The first public acknowledgment of this month's unrest came Tuesday, when a health official told reporters in Beijing that "the problem the public has recently raised is primarily not about epidemic control itself but is focused on measures being simplified, intensified and rigidly uniform." The government also announced a plan to accelerate vaccinations for people 60 and older, and urged local officials to redouble efforts and use big data to track down those in need of shots.

Yet critics fear that arbitrary and excessive measures are a feature rather than a bug of the policy, even as it begins to be modified. The vast amounts of power handed to low-level officials tasked with enforcing lockdowns has drawn comparisons to the era of Mao, when the party was involved in every aspect of everyday life. Detailed instructions written by law students have circulated online telling residents how to use Chinese laws to combat neighborhood authorities who want them to stay at home.

Nationalist commentators, many of whom claim to speak for the masses, are struggling to respond to the outpouring of anger. Some were confronted over their vague insinuations about foreign agitators. One widely shared article blaming "evildoers in the crowd" sparked so much mockery that the author deleted it.

Ming Jinwei, a former editor at state-run Xinhua News Agency turned political blogger, wrote on WeChat that while not everyone with complaints was a foreign agent, the threat of "hostile foreign forces" remains very real and present. Alongside American intelligence agencies and human rights groups, he listed Chinese people who are "spiritually American" or Western media as examples.

"Whenever there is misfortune or tragedy in China, they will attack and fan the flames," he wrote on Monday.

Chinese officials often raise similar points. A meeting of the party's top law enforcement body on Tuesday urged a "resolute crackdown on infiltration and sabotage activities by hostile forces."

Questioned about the detention of a BBC journalist in Shanghai during the protests, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian responded, "How come the BBC is always involved in troubles at the scene? This is a question that requires some serious thinking."