Mary Balcerzak, who is coronavirus-positive, sits in an isolation room inside the Kent Hospital emergency department. (Joyce Koh/Washington Post )

Stars and Stripes is making stories on the coronavirus pandemic available free of charge. See more stories here. Sign up for our daily coronavirus newsletter here. Please support our journalism with a subscription.

WARWICK, R.I. —Mary Balcerzak's nightmare was coming to an end. The coronavirus-positive woman spent 10 hours sitting with other infected patients in a small emergency department meeting room before health-care workers were able to find a bed for her in tiny Room 25. Now, 36 hours after she arrived, Balcerzak, 70, was about to move upstairs where she belonged, to a bed on a floor inside Kent Hospital.

In a nearby hallway, five people sat in chairs, one man drinking tea, quietly talking to himself. Two elderly women lay on gurneys in another corridor. The patient in Room 28 needed to be moved to intensive care, but there was no bed available.

This is what a slow day looks like in a hospital emergency department overwhelmed by the coronavirus. On other days, health-care workers have drawn blood from patients as they sat in their cars, set up intravenous drips in the packed waiting room or shunted patients to the overflow tent outside. There was simply no other choice, no other space - and far too few staff.

"Either I take care of someone in a car or I don't get to take care of them at all. Either I take care of them in the waiting room, or they don't get care at all," said Laura Forman, director of Kent Hospital's emergency department.

"Or they wait 10 hours for care. We have people wait 10 hours or 12 hours to be seen. And if you're here for an emergency, that's not tenable."

The pandemic's fifth surge is putting emergency departments under enormous stress. In March 2020, as the crisis began, doctors worried whether intensive care units would be able to handle the deluge of critically ill patients, whether they could scrounge up enough ventilators for all the people who would need them.

This time around, with a less deadly but vastly more contagious variant, the greatest damage is at the hospital system's front door, where emergency rooms that turn away no one are trying to cope with an unprecedented tide of patients and too few staff to treat them.

"We are struggling, and at times failing, to take care of people who come through the door," Forman said, "because of lack of staffing, because of lack of space, because of lack of resources."

She urged people to do all they can to avoid seeking emergency care.

"Now is not the time to take up a new sport. Do not go skiing. Shovel your back stairs and salt the living daylights out them," she said. "Now is not the time to break an ankle. . . . Take your medications. Do all of the preventive things that you can do to possibly keep yourself out of the hospital right now."

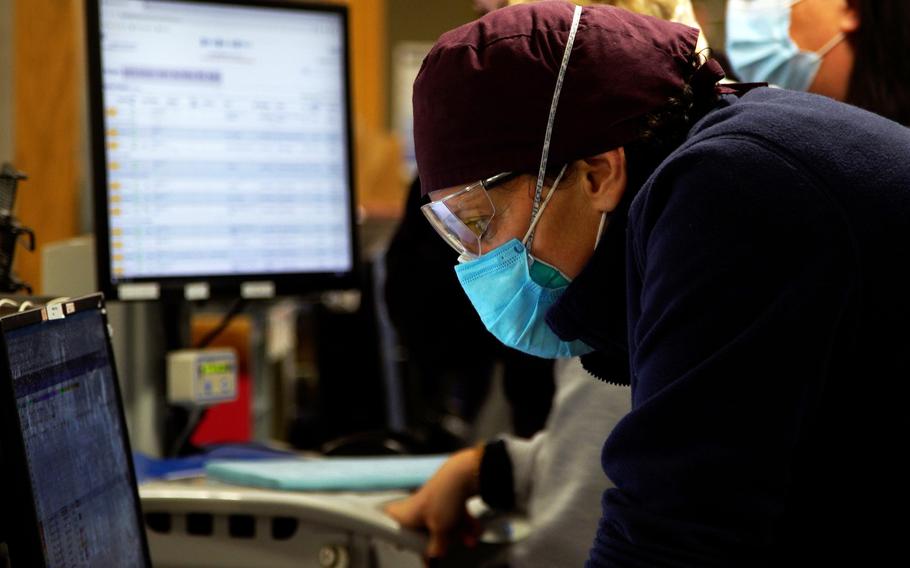

Laura Forman, director of Kent Hospital’s emergency department, checks patient details. (Joyce Koh/Washington Post )

On Thursday, when The Washington Post spent an afternoon in Kent's overburdened emergency department, this tiny state of 1.1 million people recorded 5,171 new coronavirus infections, or 488 per every 100,000 residents - the highest rate in the country, according to the seven-day average of data tracked by The Post. Nationally, there were 794,202 new cases.

At nearly 78% fully vaccinated, Rhode Island is much better than average. Forman has not seen a single vaccinated person die in the current surge.

Many experts believe the reported infection rate does not reflect the true extent of the omicron variant's spread, because people who prove to be positive on at-home tests do not always report the results to public health authorities, and because a larger number of infected people appear to be asymptomatic during the omicron wave.

At Kent, a medium-size community hospital, 144 patients were seen in the emergency department Thursday, about 30 of whom had developed covid-19. The others had maladies that could not be ignored: chest pain, appendicitis, broken bones, a gall bladder that must be removed. An allergic reaction to the dye used in CT scanning drew a scrum of health-care workers who restored a patient's breathing. Ambulances arrived in a steady stream.

Before the pandemic, the doctors, nurses, respiratory therapists and other health-care workers were on top of this. Staff and space were tight but adequate. For the most part, there were beds in the hospital for those who needed them. From 2016 to 2019, Kent's emergency department closed its waiting room. Every patient was seen within minutes, and the space was considered superfluous.

Now, about 20% of patients who register at the front window tire of the long, exhausting waits for care and leave without being seen. Before the pandemic, that figure was less than 2%.

In a 2018 survey of emergency departments nationwide, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that 43.5 percent of the nation's 130 million emergency patients were seen by a doctor, nurse or physician assistant in less than 15 minutes, and another 30.6% were seen in less than an hour.

Vacancies among Kent's nursing staff have reached 50% at times, as burned out nurses have quit and others have fallen ill with covid, Forman said. There are emergency department shifts when five nurses are working instead of the 15 who should be on duty.

Patients "wait a lot longer. They wait for pain medicine. They wait for antibiotics. They wait for their food. There's no one to notice right away if something happens," Forman said.

The former triage area and a small conference room where patients' families were given bad news privately have been converted to hold patients such as Balcerzak. Sometimes there is no one to staff the overflow tent erected outside the emergency room door.

Caregivers are forced to make difficult choices among patients, rather than treating them all. The medically stable, including covid patients, are stashed somewhere until a doctor or nurse can see them, or even sent home when doctors would like to keep them for more care.

"A lot of best bad decisions are being made," Forman said. "There's a lot of making do. There's a lot of doing something that you understand is suboptimal because it's the best option you have. And there's this sense of failure all the time."

Emergency medicine physician Anne Dulski, center, speaks with Stanley Lomas, who arrived at Kent Hospital by ambulance with chest pains. Nurse Alex Boie, left, assists Dulski. (Joyce Koh/Washington Post )

Stanley Lomas, 69, who suffered a previous heart attack, was whisked back to a bed and seen by emergency medicine physician Anne Dulski when he arrived by ambulance with chest pain Thursday. Dulski spoke with him and concluded he was stable. A nurse went over his list of medications. A technician began setting up an X-ray.

Balcerzak, in contrast, endured a nearly two-day odyssey through the emergency department. She is vaccinated but decided to put off her booster shot until after the holidays because she heard it might make her ill.

A diabetic, she tried to ride out a fever of 103 degrees, muscle aches and severe diarrhea at home. But when her blood oxygen level slid to 84%, a dangerous level, a doctor told her to seek emergency care.

For about 10 hours, she and other covid patients sat in the small room with little attention from staff, she said. No one spoke, she said; they were all too ill with covid.

"They sit you in that room there with no facilities, and you sit and you wonder 'Why did I come in if this is so dangerous and scary?' " she said. Doctors were giving her supplemental oxygen through a nasal cannula.

"For the country that we live in, this is so not acceptable. This is not the way it should be."

President Joe Biden announced Thursday he would send 1,000 military medical personnel to overwhelmed hospitals in six states, including Rhode Island. They will join about 400 other active-duty troops and 15,000 National Guard members across the United States who are already deployed in the same way.

Kent is scheduled to receive 14 of the new staffers, Forman said, including, she hopes, emergency department nurses and respiratory therapists.

On Thursday, there were only enough medical personnel to staff 199 of the hospital's 359 licensed beds. With space there at a premium, emergency department patients who must be hospitalized wait days for a bed to open, even in intensive care. They take the spots that should go to walk-ins, who as a consequence must be seen wherever Forman's doctors and nurses can put them.

This holding pattern is known as "boarding," an unwanted feature of emergency care across the United States long before the pandemic. On Thursday, 20 of the Kent emergency department's 43 medical beds were occupied by boarders, a relatively small number. On Monday, there were only six beds open for newcomers, said Mike Quas, a 20-year emergency physician.

"Our ER now has become a floor ward," Quas said, noting that at times it houses more admitted patients than any other unit in the hospital. Quas has performed medical procedures in the triage beds at the front of the emergency department, including a recent cardioversion to restore a patient's normal heart rhythm. It was safe to do so, but not appropriate care, he said.

"The triage area is for triaging, not treating," he said.

Staff shortages create other problems. The routine activities of a hospital occur more slowly when there are not enough people to perform them. Lab tests, food delivery and cleanup all take longer than they should. Elective procedures have been paused for two weeks. On certain days it is impossible to get an MRI or an ultrasound.

But patients keep coming to emergency departments everywhere.

"We're seeing people who have acute emergencies, ranging to people who are there for routine tests because they can't get routine tests anywhere else," said Gillian Schmitz, president of the American College of Emergency Physicians. "Everything backs up into the emergency department."

Forman has delivered emergency care in Bosnia, Burundi, Nicaragua and Madagascar. Just over a year ago, she helped the state open a field hospital for the patient overflow during the surge in December 2020 and January 2021.

This year, there is no field hospital. She knows her decimated staff cannot keep this up forever. Some are badly traumatized, weeping in her office, unable to continue.

"A couple years ago, we thought we'd do this for a couple of months and we'd be OK. You can do anything for a couple of months," she said. "You can't do it for a couple of years, and that's what we've been asking people to do."

She has stopped asking patients whether they are vaccinated. It was the only way she could figure out to avoid the anger and resentment she felt when treating people whose choice represents a direct threat to her and her colleagues.

Cara Newsham, 40, a respiratory therapist, considered quitting in September when her license expired, after 20 years at Kent. In the end she decided to stay.

"This is what I do," she said. "It's my passion to take care of people, to get people better. And we're all in this together, and I don't want to leave my co-workers behind."

___

The Washington Post's Alice Crites, Jacqueline Dupree and Joyce Koh contributed to this report.