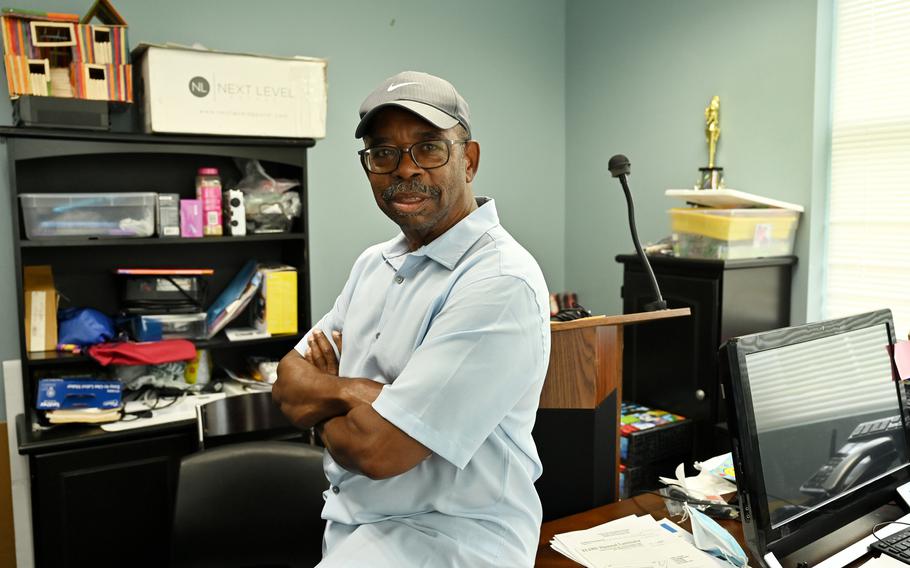

Lewis N. Watson, who owns Lewis N. Watson Funeral Home in Wicomico County, Md., has been urging people in the area to get a coronavirus vaccine. A nearby Zip code has the lowest vaccination rate in the state. (Marvin Joseph/The Washington Post )

PRINCESS ANNE, Md. — Lewis N. Watson, a mortician and pastor on Maryland's Eastern Shore, has seen his share of covid-19 losses here over the past year and a half.

At the height of the pandemic, about 7 out of every 10 deaths handled by the Lewis N. Watson Funeral Home in Wicomico County were from the virus.

Then, the numbers began to drop. By late winter, he said, he barely saw any covid-related deaths at his funeral home.

That began to change around June, he said, when cases started again to creep up.

"It's back," he said in a somber, gravelly voice, a lingering effect from his own covid-19 diagnosis in December. "It's back."

Maryland boasts one of the highest vaccination rates in the country, with nearly 79% of the adult population having gotten at least one dose.

But not in Zip code 21853.

The Zip code, which includes the sleepy small town of Princess Anne in rural Somerset County, the most impoverished region of Maryland, has the lowest percentage of vaccinated residents in a community of its size in the state.

Fewer than 3 out of 10 people in this majority-Black community have gotten at least one vaccine dose, leaving the area extremely vulnerable to the highly infectious delta variant, which has been pushing cases up to levels not seen in the state since early May.

While the community transmission rate of the virus here is now the highest it's been since February, the number of cases is relatively low - making vaccination an especially hard sell among residents.

"A lot of people say, 'I don't go anywhere, I'm not going to get it,' " said Sharon Lynch, a spokeswoman for the Somerset County Health Department.

Some Black residents mention the Tuskegee syphilis experiment, in which Black men unknowingly were denied treatment for the disease, and Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman whose cancer cells were sampled by a Johns Hopkins doctor without her knowledge and have been used for decades by pharmaceutical companies for medical research.

"They have a fear that it's an experiment," Watson said. "Some say the government is trying to put something in you to track you."

Some also question the speed at which the vaccines were developed and wonder whether the shot will do more harm than good.

Neil J. Sehgal, an assistant professor of health policy and management at the University of Maryland School of Public Health, said the low vaccination rate coupled with the rise in the delta variant means there is reason for alarm in places like Princess Anne and Somerset County.

"All it would take is a couple of events that would reasonably infect a large portion of the population," he said.

Sehgal said the challenge is ensuring that people understand the risk they face.

"We know there is a way to keep people out of the hospital," he said. "The problem we haven't solved is to . . . foster the trust in the communities that are most likely to benefit" from that knowledge.

- - -

Before he begins his regular weekday morning prayer conference call, the Rev. Carroll L. Mills makes a plea to those on the line.

The Rev. Carroll L. Mills of Mount Carmel Baptist Church in Princess Anne, Md., says he's frustrated at the vaccine hesitancy in his community. (Marvin Joseph/The Washington Post)

"We still know that covid is alive and well," Mills told the members of Mount Carmel Baptist Church and others who dialed in for a recent 6:30 a.m. call.

He implores them to get vaccinated. For anyone who is already inoculated, he urges them to pray for those who aren't and to encourage them to get the shot.

"It's so crucial and so important," he said.

Mills is frustrated, unable to understand how people who have friends or relatives who have died of covid-19 could "play Russian roulette with their lives."

He held one pop-up vaccination clinic at his Princess Anne church this spring where about 200 people were vaccinated - but he can't hold another one because he can't get 50 people, the minimum number required, to sign up.

During a three-day span in early August, as cases began to surge in Maryland, Mills learned that the grandmother of one of his young members had died of covid-19 and the unvaccinated daughter of another member had contracted the virus.

"It's a matter of life and death," he said. "The Bible says, 'Our people perish for a lack of knowledge.' And yet once you give the people the knowledge, they don't want to take the responsibility of the knowledge that they've learned."

One of the challenges health officials face is convincing residents who have not experienced a devastating toll from covid-19, as other parts of the country have, that it is still important to get vaccinated.

There have been 796 coronavirus cases among the 11,126 people who live in the 21853 Zip code, which is about 7% of the population. By comparison, some of the state's areas hardest hit by the pandemic, including parts of Prince George's County and Baltimore City, have had about 9% of their populations contract the virus.

Last month, Somerset County was hosting pop-up clinics every day. When vaccines first became available this year, the clinics would see 100 people. Sometimes now, said Lynch, the health department spokeswoman, they may reach just one or two people at a time - and they celebrate each one.

"Two unvaccinated people here is a huge difference in percentage points than two people in Baltimore City," she said.

Yen Dang, an associate professor of pharmacy and the director of global health at the University of Maryland Eastern Shore, said the reasons vary as to why the community has taken a "wait and see" attitude and in some instances refused to budge on getting a shot - even after the deaths of loved ones, incentive programs and outreach campaigns.

She said the community has limited access to health care and many residents haven't seen a doctor in years, sometimes decades, leading to mistrust of medical and science authorities.

And despite having low-paying, essential-worker jobs that have put them at higher risk of exposure to the virus over the past year, they remain skeptical of government officials and what they have said about the vaccine.

"There is a mind-set that covid is over, we're getting back to normal," Dang said.

Watson, who now has a growth on his vocal cords that doctors say is a side effect of his covid cough, knows people who have breathing problems, kidney dysfunction and memory loss - all from having covid-19.

He is hoping that if he, Mills and other pastors talk about the virus and the vaccines, "explaining the importance of the vaccination and what science is saying, not what your opinion is about, not what government is saying, but about the scientific proof that people are dying because they are not vaccinated," the numbers will shift.

"When you get in your car you put on your seat belt. It's for your safety," he said. "If you get in a car accident . . . with your seat belt on, it reduces the risk of you losing your life. Same with the vaccination, it reduces your risk of you losing your life."

- - -

At age 71, longtime Princess Anne Town Commissioner Garland Hayward was eligible to get a vaccine in March. He didn't get it until June.

Princess Anne Town Commissioner Garland Hayward was originally skeptical of getting the vaccine, but eventually he relented. (Marvin Joseph/The Washington Post )

"Everybody was asking, 'Are you going to take the shot?' and I would say no," Hayward said.

It wasn't that he thought the pandemic was a hoax - quite the contrary, he said. He said the vaccine was produced too quickly for him and he was afraid of potential side effects.

He thought the virus could be avoided through other ways, like social distancing.

"I personally think we opened up too soon," Hayward said. "People have let their guards down." He said those who haven't gotten the virus after more than a year and a half of the pandemic think at this point that they don't need a vaccine.

He changed his mind because he wanted to continue to see his young grandchildren without fear of getting the virus from them.

Now, he is in talks with his colleagues on the town commission about using some federal pandemic relief money to offer an incentive to unvaccinated residents - even though he said an incentive would not have swayed him when he was refusing to get the shot.

Andrea Byrd, 56, who works with Hayward at a local recreation center, said she eventually decided to get a vaccine after nagging from her 78-year-old, vaccinated mother and urging from her doctor, who treats Byrd for seasonal asthma.

Looking back, Bryd said she was firm in her decision, which she realizes now, she said, was based on "lack of knowledge or information. I heard so many tales about the vaccination: what it could do to people, how effective it was and that was going off of hearsay."

She said she constantly heard from family, friends and social media posts that the vaccines were risky, causing blood clots and resulting in hospitalizations.

"I was like, 'Wow, I'm not doing this,' " said Byrd, who had remained apprehensive about the vaccines even after losing cousins to covid-19.

She's glad she got a vaccine in June, realizing that it doesn't exempt her from contracting covid-19 but "protects us from having the harsh part of it."

Now, like her mother did with her, she is trying to persuade her 33-year-old son to get vaccinated.

"He refuses," she said. "I tell him Mom-Mom did it, I did it, your sister did it, your aunts did it."

He tells her it isn't effective; that he's doing everything he is supposed to do to stay healthy and that he feels fine.

Mills said he is continuing to pray that something will move more of the city's residents to get vaccinated.

"Vaccinations have been a part of everybody's life since birth," he said. "The same vaccination that they took for measles and other stuff was lifesaving. This vaccination is lifesaving. To me, you shouldn't have to give someone an incentive to save their life. . . . I don't know what's going to make them move."