Sailors prepare for flight operations on the deck of the Nimitz-class aircraft carrier USS Carl Vinson on Jan. 12, 2025, in the South China Sea. The Vinson is underway conducting routine operations in the U.S. 7th Fleet area of operations. (Petty Officer 3rd Class Nathan Jordan/U.S. Navy photo )

ARLINGTON, Va. — Projections by Navy leaders that the U.S. could be at war with the Chinese by 2027 is driving the sea service to revamp how it repairs and upgrades ships and train crews so more of the fleet is ready for a potential fight.

“We can’t continue to do things the way we have been,” Vice Adm. Brendan McLane, commander of Naval Surface Force Pacific Fleet, said last week during the Navy Surface Warfare’s 37th National Symposium.

In recent years, the Navy has been plagued with monthslong construction delays on new shipbuilding programs, as well as maintenance woes on aging ships that threaten deployment schedules. The longstanding issues have caused a backlog of ships going in and out of shipyards. The Navy was on track for a 67% on-time maintenance completion rate across the fleet in 2024. That comes after a 36% completion rate in 2022 and a 41% completion rate in 2023.

Meanwhile, deployable ships are spending additional time at sea, and in the case of West Coast ships, have been pulled from one area of operations to another.

The backlogs coupled with an increased operational tempo have led to concerns about how many U.S. ships are ready to fight and a possible conflict with a growing Chinese navy. The U.S. Navy is structured to have 1/3 of the fleet in maintenance, 1/3 in training and 1/3 on or ready for deployment. But persistent delays across all phases of a ship’s lifecycle could mean ships are not ready for a fight.

To address this, Adm. Lisa Franchetti, chief of naval operations, put forth in the fall an initiative in her 2024 Navigation Plan for the Navy to have 80% of the fleet ready for a possible fight with China by 2027 — what she described as “a stretch goal.”

“We need a bigger fleet, every study we’ve done since 2016 shows that, but it will take years and significant resourcing to expand our traditional industrial base to produce the platforms, the munitions, and the capabilities at the scale we need. And our entire Navy team is committed to working with all of our stakeholders, industry, Congress, and [the Office of the Secretary of Defense] to pull every lever to put more players on the field,” Franchetti said during the symposium.

Navy leaders gathered at the symposium to offer calls to action that they said could help propel Franchetti’s plan.

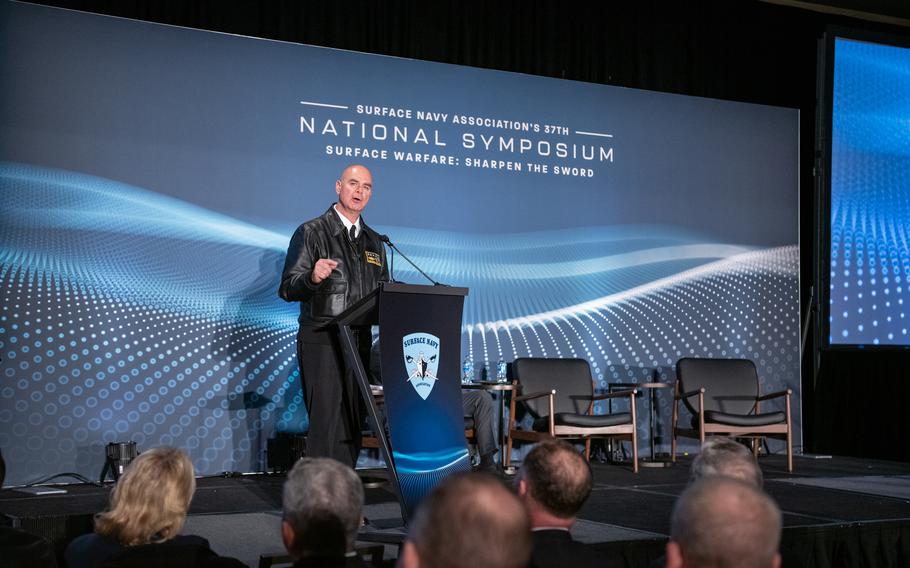

Vice Adm. Brendan McLane, commander of Naval Surface Forces, delivers an update on the status of the force on Jan. 14, 2025, at the Surface Navy Association’s 37th National Symposium in Arlington, Va. The symposium brings together experts and decision-makers in the military, industry, and Congress to discuss how the surface force is a critical element of national defense and security. (Claire M. Alfaro/U.S. Navy)

McLane showcased updates to “Surface Warfare: The Competitive Edge,” a strategic document released in 2022 that outlined the steps the Navy should take to improve the combat capabilities of its ships. The document was updated to bring it in line with the Navy’s 2024 Navigation Plan goal of having 80% of its ship’s ready for combat by 2027.

The update put the Navy on notice to shorten its basic phase, tier one training certification from 15 weeks to an average of 10 weeks by June 2026. Being certified in tier one means the ship has completed the initial level of readiness and is considered combat ready. The phase is meant to take 10 weeks but has stretched to an average of 15 weeks because the Navy hasn’t stocked ships with spare parts necessary for at-sea, sailor-led maintenance. In stocking ships was “just in case” spare parts, McLane said, the ships will spend less time waiting for parts to arrive and more time on task.

Additionally, the Navy wants 71% of major repairs and overhauls completed on time, and to keep delays to less than 1,714 days. Those maintenance periods are meant to be finished between 180 days and about 1,100 days, depending on the complexity of the work.

In line with this effort, Naval Sea Systems Command released a five-part plan this week that includes getting new ships in the water on time while also creating more maintenance opportunities for existing ships. The command is responsible for designing, building and maintaining Navy ships and combat systems.

“What we are not doing is deferring maintenance,” Vice Adm. James Downey, commander of Naval Sea Systems Command, told reporters last week.

Rather, the command is working to shave months off a ship’s time in dry dock — scaling it back from one year to about five months. Downey said the new strategy is the result of an enterprise-wide, self-assessment process that will make the organization better over time.

“Nothing was off the table when we started this process last May, and since then, we’ve realigned departments, merged similar functions, and streamlined command operations to enable greater focus on these lines of effort,” he said.

The Navy should focus on designing its future ships with an eye on simplicity, according to Dan Grazier, a senior fellow for the National Security Reform Program at the Stimson Center, a Washington think tank.

“Simplicity and ease of maintenance should be top design requirements,” he said. “Back in the 1940s, the Navy was able to turn heavily combat-damaged ships around in a matter of weeks — get them back into the fight. That is an impossibility today.”

But the maintenance backlog is not a problem that will likely be solved by 2027, Grazier said. It is an opinion that was shared during the Navy symposium by Adm. Daryl Caudle, U.S. Fleet Forces commander.

“We know our force structure will certainly not change between now and 2027 and will not significantly change over the next decade,” he said. “Bottom line: We must be constantly making ready ships not in depot or currently deployed.”

At any given time, the Navy has about 100 ships deployed around the globe, 100 in lengthy maintenance depots and 100 that are between deployment and maintenance depot. Caudle said the Navy is targeting the 100 that are not deployed or in depots and working to train them to be certified for a combat surge.

This would mean the ships receive a formal designation that the platform and crew are ready and able to fight at a moment’s notice. But those ships might have to surge into combat with less capabilities.

“I need more ordnance, I need more parts, and I need more ships. But I have to fight with the Navy I’ve got,” Caudle told reporters.

The strategy that Caudle highlights is “theoretically achievable,” but its success will depend on the risk that Navy leaders are willing to take in certifying ships are combat ready despite missing a capability or two, according to Mark Cancian, a senior adviser at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, another Washington think tank.

“If you want to have more ships ready to deploy in 2027, then you would logically have to give up some longer-term capabilities in order to make that happen. It is all about tradeoffs,” he said.

Grazier echoed Cancian, but noted while the plan is viable, it is a slippery slope that could result in ships needing an unanticipated capability during combat.

“But I think it’s the only option the Navy has right now,” he said. “I think they are kind of out of options to meet the 2027 goal. It is really breathing down our necks.”