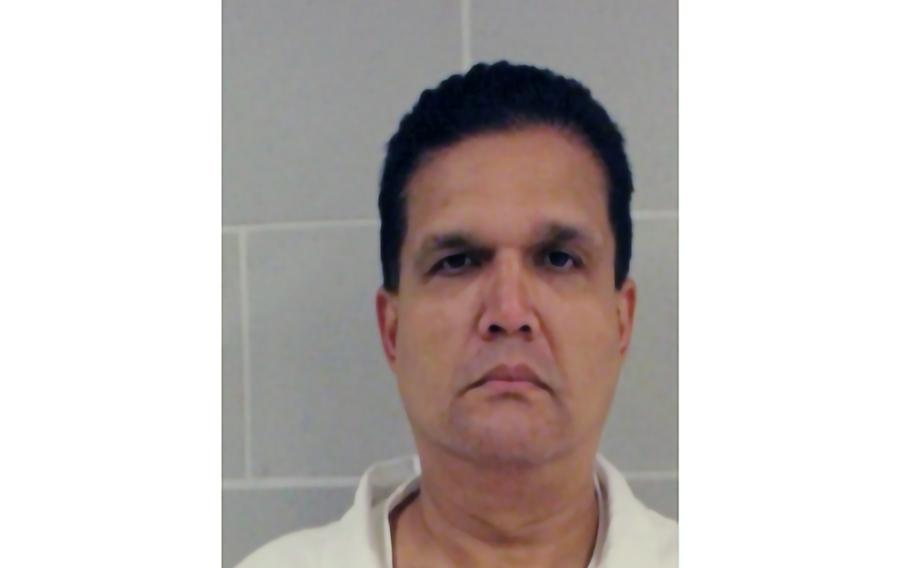

This undated photo provided by the U.S. Marshals Service shows Leonard Francis, also known as “Fat Leonard.” (U.S. Marshals Service)

Few Navy officers entangled themselves in the Fat Leonard corruption scandal more than Steve Shedd. In court documents and testimony, the former warship captain confessed to leaking military secrets on 10 occasions for prostitutes, vacations, luxury watches and other bribes worth $105,000.

On the witness stand in a related case in 2022, Shedd also admitted that he had lied repeatedly to federal agents and betrayed his oath to defend the Constitution.

“You’re a traitor to the United States, aren’t you?” attorney Joseph Mancano asked the Naval Academy graduate.

“Yes, sir,” Shedd replied, acknowledging that he was “a disgrace” who “deserves prison.”

Yet because of mistakes by the Justice Department, Shedd might avoid punishment for his crimes.

Two years ago, Shedd pleaded guilty to bribery and conspiracy charges for taking payoffs from Leonard Glenn Francis, a 350-pound Malaysian defense contractor known as Fat Leonard. Under terms of his plea deal, Shedd agreed to pay the government $105,000 in restitution and faced a maximum of 20 years in prison.

On Tuesday, Justice Department officials are scheduled to ask U.S. District Judge Janis Sammartino in San Diego to dismiss the entire case against Shedd. The reason: a pattern of prosecutorial misconduct in the Fat Leonard investigation that has caused several cases to unravel so far and is threatening to undermine more.

Shedd’s attorneys declined to comment but have filed legal briefs supporting the dismissal.

In addition to Shedd’s case, federal prosecutors in the Southern District of California are proposing throwing out the felony guilty pleas of three other retired Navy officers and one retired Marine colonel who admitted pocketing bribes from Francis. If the judge approves, they’ll be allowed to plead guilty to misdemeanors instead, with no prison time.

The cases collapsed after defense attorneys alleged that prosecutors from the U.S. attorney’s office in San Diego relied on flawed evidence and withheld information favorable to the defense during the 2022 bribery trial of five other officers who had served in the Navy’s 7th Fleet in Asia. Each was accused of accepting extravagant meals and gifts from Francis, whose maritime-services company once held $200 million in federal contracts to resupply Navy ships in ports throughout the Western Pacific.

Though a jury found four of those defendants guilty, Sammartino vacated their felony convictions in September and lambasted prosecutors for “flagrant and outrageous” misconduct.

The striking reversals have given the Justice Department a black eye and undermined the quest for accountability in the most extensive corruption case in U.S. military history. After Francis’s arrest in 2013, nearly 1,000 individuals came under scrutiny, including 91 admirals. Federal prosecutors brought criminal charges against 34 defendants. Twenty-nine of them, including Shedd, pleaded guilty.

In a court filing in April, a new set of prosecutors from the U.S. attorney’s office in San Diego acknowledged “serious issues” with its handling of the 2022 trial and said they are reviewing more closed cases to determine whether other defendants “merit relief.”

The prosecutors did not specify how many cases might be reopened. Besides the five cases being heard in court this week, as many as two dozen additional defendants could be affected.

Most have already completed their prison terms, but the Justice Department could ask the judge to erase their felony records or allow them to plead guilty to lesser charges.

“It potentially could taint almost everything,” said Rachel VanLandingham, a law professor at Southwestern Law School in Los Angeles who has followed the case. “It is going to be really interesting to see if the wheels come off for the entire train.”

She said the Justice Department has a duty to hold itself accountable for its errors and to treat defendants fairly, even if that lets offenders off the hook for what she called the “most extensive, tawdry and ethically problematic scandal” in the 248-year history of the Navy

“We can’t afford a criminal justice system that cuts corners,” she said. “It does mean that [sometimes] individuals go free even when they’re guilty as hell.”

Kelly Thornton, a spokesperson for the U.S. attorney’s office in San Diego, declined to comment.

Legal analysts said it is possible that even Francis might catch a break, though he has already pleaded guilty to bribing “scores” of military officers and defrauding the Navy of tens of millions of dollars. He is being held in a San Diego jail while he awaits sentencing. His attorney, William Sprague, did not respond to emails seeking comment.

“I can guarantee you that every defense lawyer is talking to their client, trying to figure out how to move forward,” said Sara Kropf, a trial lawyer in D.C. who is not involved in the case but has monitored the proceedings. “I’d call the prosecution and say, ‘Can we work something out?’ ”

During the 2022 trial, subsequent court filings show, the prosecution team led by Assistant U.S. Attorney Mark Pletcher withheld a witness statement that contradicted some of the government’s allegations and did not divulge that one of its lead investigators had made inaccurate statements in another case.

Defense attorneys also accused prosecutors of concealing how Francis received cushy privileges — including gourmet meals and manicures and pedicures — while he was a prisoner during secret debriefings at the U.S. attorney’s office. The debriefings occurred as part of a cooperation agreement that Francis reached with the Justice Department to provide evidence against hundreds of Navy officers.

Pletcher and other members of his prosecution team have since been reassigned from the case. One of the defense attorneys involved in the trial filed a complaint against Pletcher with the Justice Department’s Office of Professional Responsibility in August 2022, alleging that he willfully concealed evidence favorable to the defense.

In March 2023, a Justice Department official responded in writing, saying the office had “carefully reviewed” the complaint but closed the inquiry after determining that “further investigation was unlikely to result in a finding” that Pletcher intentionally violated any rules or acted “with reckless disregard.”

Pletcher did not respond to a request for comment.

Shedd and the four other defendants seeking leniency pleaded guilty before the start of the 2022 trial that became marred by misconduct. But in court filings, prosecutors said it would be unfair to punish them more harshly than the Navy officers whose felony convictions were thrown out.

“These defendants accepted responsibility for their crimes and cooperated, some extensively,” First Assistant U.S. Attorney Peter Ko wrote in a brief last month. Yet, he added, “they inequitably face much harsher outcomes than their immediate co-conspirators who did not accept responsibility, did not cooperate, and opted for trial.”

Shedd was the only one who testified as a prosecution witness at the 2022 trial, which is why prosecutors say he deserved to have all charges against him dismissed. In a legal brief, his attorneys called him a “critical” government witness, noting that “he was required to, for the very public record, lay bare personal failings.”

Besides Shedd, the four others seeking to withdraw their felony guilty pleas are retired Navy Capt. Donald Hornbeck, Cmdr. Jose Luis Sanchez, Chief Warrant Officer Robert Gorsuch and Marine Col. Enrico DeGuzman.

Under terms of their new arrangement with the Justice Department, each would plead instead to a single misdemeanor charge of improperly disclosing government information. All formerly served on the staff of the Navy’s 7th Fleet, which oversees U.S. maritime operations in the Western Pacific and Indian Ocean.

Sanchez, a logistics officer, had originally pleaded guilty in January 2015 to bribery and conspiracy to commit bribery. In doing so, he admitted leaking classified information to Francis on seven occasions between 2009 and 2011.

In return for serving as the Malaysian businessman’s paid informant, Sanchez acknowledged receiving prostitutes, swanky meals, free travel and other bribes worth between $30,000 and $120,000. Emails and text messages show that he addressed Francis as “Boss.” His attorney, Vincent Ward, declined to comment.

Gorsuch served as the flag administration officer to the three-star admiral in charge of the 7th Fleet from 2005 to 2008. In August 2021, he pleaded guilty to pocketing $45,000 worth of meals, hotel rooms and other gifts from Francis. He also admitted that he leaked military secrets.

Francis told federal agents that Gorsuch once escorted him onto the U.S. Navy base in Yokosuka, Japan, and handed him two disks containing classified ship schedules. “No worries about helping you out - any time my friend,” Gorsuch emailed Francis afterward, according to a copy of the message. “It was my pleasure.”

Gorsuch’s attorney, Frederick Carroll, did not respond to emails seeking comment.

Hornbeck served as the 7th Fleet’s assistant chief of staff for operations from 2005 to 2007. He pleaded guilty to a bribery charge in February 2022 and admitted accepting prostitutes, meals and other gifts worth at least $67,000. Francis told federal agents that he nicknamed Hornbeck “Bubbles” because he drank so much champagne, documents show. Hornbeck’s attorney, Benjamin Cheeks, did not respond to emails seeking comment.

DeGuzman, a Marine, served as a senior officer on the 7th Fleet staff from 2004 to 2007. He pleaded guilty to a bribery charge in September 2021, admitting that he had taken meals, hotel rooms and other gifts worth at least $67,000. His attorney, Hamilton Arendsen, did not respond to emails seeking comment.