Seaman Recruit David “Dee” Spearman, assigned to the destroyer USS Arleigh Burke, died after going overboard Aug. 1, 2022, while the ship was operating in the Baltic Sea. (U.S. Navy)

A Navy sailor who died after falling off a destroyer in the Baltic Sea was cleared for full duty despite a history of dangerous fainting episodes, including one while at the helm of the ship.

Seaman Recruit David Spearman lost consciousness at least four times in the weeks before his death in the summer of 2022 and repeatedly sought help from medical staff aboard the USS Arleigh Burke, according to a Naval Criminal Investigative Service report, a copy of which Stars and Stripes obtained through an information request.

About two weeks after collapsing while steering the ship in early July 2022, Spearman was returned to duty without restrictions even though he again had lost consciousness, badly cutting his face, NCIS investigators found.

At about noon on Aug. 1, 2022, Spearman skipped lunch and was working alone when he went overboard.

After fighting for at least 10 minutes to stay afloat in the cold water, he sank below the surface of the dark sea, moments before a search and rescue swimmer arrived, according to the report.

The 346-page document reveals that the ship’s senior officers must have been aware of Spearman’s well-documented collapses yet did little to keep the 19-year-old safe, a Stars and Stripes investigation found.

“I do believe his death could have been 100% prevented, and I feel he needs justice for his death and for his family,” one of the ship’s sailors said in an Aug. 13, 2022, statement to investigators. NCIS redacted the names of the people interviewed.

The findings lay bare additional failures in communication and decision-making, experts said.

Stars and Stripes’ investigation into Spearman’s death also revealed lapses in how the Navy reports and studies man-overboard events.

Since Nov. 17, Stars and Stripes has repeatedly sought comment from the Navy about the report and answers to questions about the circumstances surrounding Spearman’s death.

The Navy acknowledged those questions and said it’s working to gather the information. After nearly two months, the service has not provided answers.

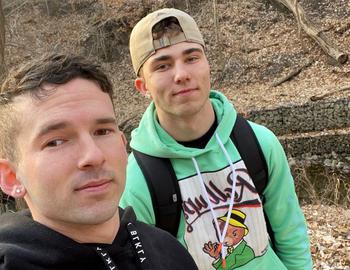

Seaman Recruit David "Dee" Spearman, right, is shown in this undated photo with Petty Officer 3rd Class Austin Donohoe. Spearman and Donohoe met during boot camp and maintained their friendship when both were assigned to Naval Station Rota in Spain. Donohoe described Spearman as a fun-loving person who liked to make other people laugh. (Austin Donohoe)

Known to family and friends as Dee, Spearman was well-liked by his fellow sailors, the report shows. They recalled that he was always smiling and liked to joke and have fun, but also had a strong work ethic.

“Spearman was a hard worker and knew the work day wasn’t over until the work was completed,” one sailor told investigators.

His family’s grief is compounded by open questions about what caused their son’s death, whether it was preventable and whether any actions were taken in response.

The Navy did not fully explain to his parents what happened, but they did receive a copy of the NCIS report in August, on the one-year anniversary of his death, said his mother, Nikki Spearman.

While the report offered more details about their son’s drowning, it also provoked serious questions about the actions of ship officials, said Lee Spearman, Dee’s father.

“My son should have never been up on the deck working after he’s passing out while steering the ship,” Lee Spearman said. “We’re pro-military, but I am not pro-negligence. After reading the report ... I’m not sure if there wasn’t some negligence on the part of the military.”

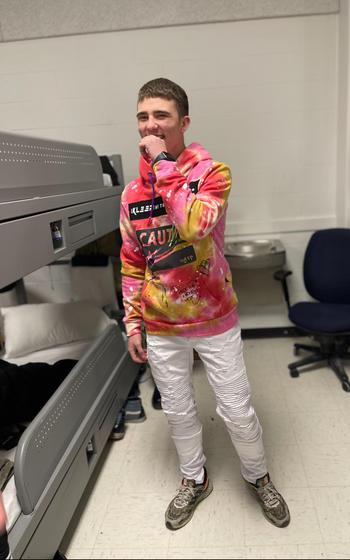

Seaman Recruit David "Dee" Spearman, 19, had been in the Navy for less than a year when he fell overboard the destroyer USS Arleigh Burke while transiting the Baltic Sea. (Austin Donohoe)

Overboard data lapses

Spearman was one of two people who died in 2022 after going overboard Navy ships, according to Naval Safety Command data.

The command, which is responsible for studying mishaps involving Navy ships and personnel, only tracks man overboard incidents involving accidental entry into the water.

Over the past 13 years, the command recorded 82 such incidents, five of which were fatal, according to the data. But a quick review of Stars and Stripes stories over the same time period showed at least seven other man-overboard deaths that aren’t part of the data.

Those fatalities include a 20-year-old sailor who fell off the USS Theodore Roosevelt in December 2020 and a 29-year-old petty officer second class lost from USS Nimitz in September the same year.

The safety command didn’t specifically address why those deaths and five others appeared not to be part of the data.

Determining whether a man-overboard event is accidental or intentional is based on circumstances or in some cases on the outcome of legal or safety investigations, Sarah Langdon, a spokeswoman for Naval Safety Command, said in a Dec. 6 email.

Those factors underscore the fluid and changing nature of the data, she said.

If an event initially reported as a mishap is determined to be intentional, it no longer meets the criteria for a safety mishap and therefore doesn’t fall under the command’s reporting, Langdon said.

While those fatalities could have been suicides, the Navy couldn’t immediately say how it tracked them or what department was responsible. It also didn’t answer questions about how those events in their totality are studied.

But a 2023 study on the National Library of Medicine website may give some indication of the overall impact of man-overboard deaths on the service.

The study reviewed all mishaps on active Navy ships recorded by the safety command from 1970 to 2020 and found that man-overboard events were among those with the highest mortality rates.

Over the 50 years reviewed, the study found that there were 352 man-overboard casualties, with a 71.9% mortality rate. Although death rates declined significantly in more recent years, noncombat man-overboard incidents still were the second-highest cause of injuries or death on ships and submarines, according to the report.

Fires, burns or smoke inhalation comprised the top cause of casualties, with a 13% mortality rate, the study found.

Family, friends and fellow sailors described Seaman Recruit David "Dee" Spearman as a fun-loving person who always was smiling and liked to make people laugh. Spearman, 19, went overboard the destroyer USS Arleigh Burke on Aug. 1, 2022. His body was never found. (Austin Donohoe)

Error chain

It’s unknown what caused Spearman to plunge off the starboard, or right, side of USS Arleigh Burke.

No one saw it happen and there isn’t any video, according to investigators. The NCIS report does not include a conclusion but seems to suggest that Spearman may have fainted or slipped while sanding the ship’s forward bulkhead.

Several documented losses of consciousness, some witnessed by crew members, along with Spearman’s own worries point to fainting as a probable reason he fell overboard, said Aaron Davenport, a retired Coast Guard captain who commanded two cutters and had roles as a senior safety officer and the service’s chief of cutter forces.

“My professional opinion is that (Spearman) was not fit for full duty,” Davenport said. “He probably should not have been alone based upon the number of fainting episodes.”

Statements from the ship’s executive officer, medical corpsman and other key individuals that might offer insight into awareness and decisions appear to be missing from the report, said Davenport, who was given a copy of the document by Stars and Stripes.

Those accounts may be among 162 pages redacted by NCIS for a variety of reasons, which could include protecting Spearman’s medical information or the identities of witnesses. More than 20 of the redacted pages are statements.

There are no statements in the redacted file from anyone aboard the ship above the pay grade of E-5, or petty officer second class. In two otherwise readable statements, one rank was redacted, and the other, that of a 19-year-old sailor, was left blank.

NCIS can’t say who was or wasn’t included in the investigation interviews, agency spokesman Jeff Houston said in response to questions about the redactions.

Still, the report reveals a potential chain of errors, said Davenport, now an associate director of the Rand Corp. infrastructure, immigration and security operations program.

For example, photos of two locations where Spearman is thought to have fallen overboard show that standard rope was being used in place of stronger, more durable lifelines that form a barrier around the deck to help keep sailors from going overboard.

In one case, just one of the four barrier lines was the typical black, coated synthetic lifeline used on Navy ships.

A statement from the boatswain’s mate of the watch also doesn’t appear in the redacted report. That sailor typically would be responsible for noting the condition of the ship and potential safety problems.

And it’s unknown whether Spearman’s supervisor was aware that he was working alone and whether the supervisor had checked to see if safety equipment, such as a personal flotation device, was being used if required, Davenport said.

After the episode at the helm, Spearman was relieved of watch duty by leadership and required to have someone with him when he was on the ship’s deck. He still was assigned work detail, the report shows.

“In that time, he passed out one more time,” said one sailor, who did not appear to witness the episodes but accompanied Spearman to medical care after one instance. “After two weeks, he returned to watch and we relaxed the two-person rule.”

The witness added that Spearman hated the restrictions. He tried to keep the fainting spells secret but couldn’t after blacking out at the helm.

A medical corpsman who treated Spearman said he was dehydrated as a result of sea sickness, the report shows.

Medical staff on the ship later suggested that it might be an electrolyte imbalance and that Spearman would need additional tests when Arleigh Burke returned to its homeport in Rota, Spain, according to the report.

But Spearman told fellow sailors and his family he was drinking plenty of fluids. He was frustrated that medical staff didn’t seem to be taking his condition seriously, according to the report.

“Spearman thought he had (a) neurological issue because he only passed out when the boat was really rocking back and forth,” the report stated.

There are several factors that can cause fainting, according to the Harvard Medical School website. They range from heart problems or seizures to less worrisome causes, such as overstimulation of the body’s vagus nerve.

“To me, he should have been taken off the ship for a full medical workup,” Davenport said.

Potential safety violations and the specter of Spearman’s unresolved health problem signal several factors that likely contributed to his death, rather than a single cause, Davenport said.

A separate Naval Safety Command investigation may provide deeper insights and recommendations. Stars and Stripes asked for a copy of that investigation report on Oct. 31 but has not yet received it.

Still, the NCIS report leaves open serious questions about oversight of the junior sailor on the day he died, Davenport said.

“Did somebody in a position of leadership know what (Spearman) was doing? Were they aware?” asked Davenport, who has investigated dozens of ship and personnel mishaps.

A little too late

Soon after Spearman fell off the Arleigh Burke, a sailor on watch on the right side of the ship heard someone say “help” and saw Spearman floating in the sea, according to the report.

An alert was sounded, and a life ring and smoke float were thrown to help mark Spearman’s location.

Within eight to 10 minutes, the ship launched a rigid hull inflatable boat with a search-and-rescue swimmer aboard. The ship’s commanding officer, Cmdr. Peter Flynn, told Spearman to stay calm and “assured him they were going to get him,” one sailor remembered.

But the boat crew had difficulty spotting Spearman, who was wearing a gray jacket. Radio communications between the boat and ship personnel, who could see Spearman, also were hampered, according to the report.

“There was a lot of yelling and miscommunication that day, and the small boat did not always seem to be hearing what was being instructed to them,” one sailor told investigators.

At one point, “while the boat was making an approach they actually drove past (Spearman) and initially it appeared as the boat was able to retrieve (him), only to learn that it was not the case,” the report states in summarizing the statement of one witness.

Experts say spotting a person or something else in the sea is exceedingly hard from smaller boats, which sit low in the water. Arleigh Burke would have a much better vantage point, they said.

Rough seas also can inhibit a boat crew’s ability to find a person, especially if they’re wearing blue, said a retired naval officer, who agreed to speak with Stars and Stripes on condition of anonymity to better explain the procedures involved.

Even so, the boat crew seemed to spot Spearman, and the swimmer dived into the water but was unable to reach him in time, the report states.

A second small boat was launched and joined by a Swedish rescue team, German helicopters, a U.S. Air Force U-2 reconnaissance aircraft and MQ-9 Reaper drones, according to the report.

But no trace of Spearman except for his jacket was found. He was declared dead at 11 p.m. on Aug. 2, less than 10 months after enlisting in the Navy. It was his first deployment.

Spearman was excited to be assigned to Rota and eager to learn about and explore other countries, said Petty Officer 3rd Class Austin Donohoe, who went through boot camp with Spearman and also was stationed at the installation in Spain.

Spearman was a positive person who liked to have fun and be goofy, Donohoe said, adding that Spearman “enjoyed making people laugh.”

A Naval Criminal Investigative Service investigation into the death of Seaman Recruit David "Dee" Spearman revealed the 19-year-old lost consciousness four times in the weeks leading up to him falling overboard the destroyer USS Arleigh Burke on Aug. 1, 2022. (Austin Donohoe)

Nikki and Lee Spearman remember a young man who wanted to continue a family legacy of military service.

Nikki Spearman’s father, who died in 2021, was a retired master chief petty officer. Lee Spearman’s father served in the Air Force, and his stepfather also is a retired master chief petty officer.

Their son, who had been adopted as a toddler, was energetic, liked to keep busy and didn’t hesitate to help and care for other people, they said.

He often was the hands and legs for his father, who had lost his lower limbs and other parts of his body after contracting an infection in Africa during a service mission, they said.

“Dee left a huge hole,” said Nikki Spearman, her voice breaking as she held back tears.

The family, which includes seven siblings and several grandchildren, struggles to comprehend the loss. One grandchild still writes letters to Dee as if he were alive, his parents said.

Over frequent video calls, Spearman shared details about his life as a sailor with them, including his medical condition and his exasperation about not getting proper treatment.

While the family received scant details about the circumstances of their son’s death, shipmates filled in some of the gaps, they said.

Still, there are lingering questions about why their son wasn’t wearing a flotation device while working on the ship’s deck and why he was working alone, among others.

They also want to know that any factors that contributed to their son’s death have been corrected so that other sailors are safe.

“I have all these questions,” Nikki Spearman said. “I know nothing will bring him back, but ... why?”