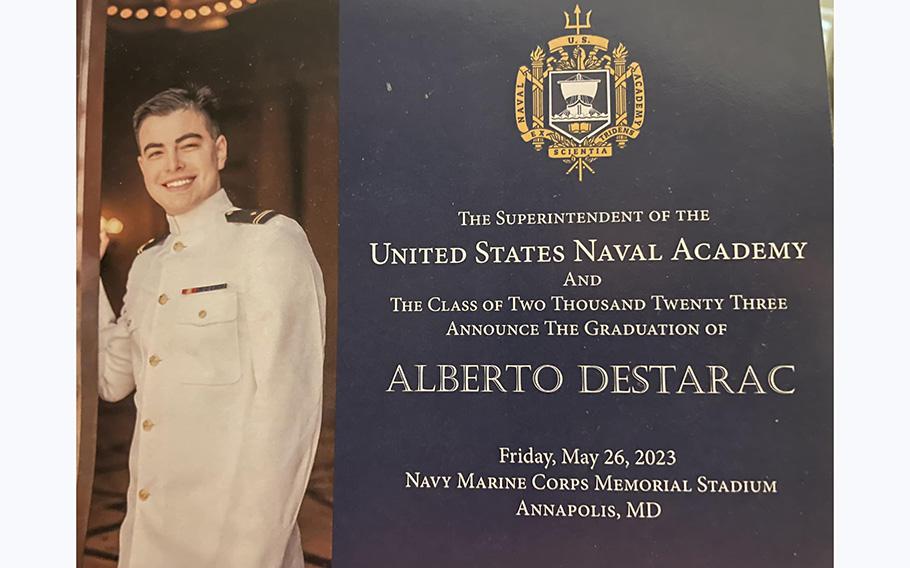

Midshipman Alberto Destarac was to graduate from the U.S. Naval Academy Friday, May 26, 2023, even though he is going legally blind from a health condition. (Facebook)

(Tribune News Service) — Like any responsible college student coping with a chronic health condition, Alberto Destarac emailed his professors last August to let them know he may need extra accommodations.

But for Destarac's professors at the U.S. Naval Academy, a school that ties graduate rates to the survival of the fittest, the emails were a shock.

"So, I'm going to be going blind this semester,'" Destarac recalled writing as he relaxed with his parents at City Dock during Commissioning Week and reflected on a yearlong roller coaster of diagnostic testing, tough decisions and unprecedented perseverance. Although Destarac, 23, is not being commissioned to serve in the U.S. military, given long-standing policies disallowing blind Americans, he will receive his degree and become, as far as he knows, the academy's first blind graduate.

"The academy works on this whole principle that no one who enters has any medical problems," Destarac said. "They couldn't really kick me out, but I had to prove that I could stay."

Over the past nine months, Destarac not only proved he could stay, he distinguished himself academically, socially and physically. On Monday, he received the first John Johnson Award for Mental Toughness, an honor bestowed in memory of a Naval Academy senior who died in a 2020 drowning accident.

"John Johnson consistently achieved excellence in every aspect of the USNA mission," Commandant of Midshipmen J.P. McCollough wrote in a February memo establishing the award. Lt. Ryan Tran, an engineering instructor and Cdr. Andrew Ledford, a professor in the Department of Leadership, Ethics, and Law at the academy, both thought of Destarac when they saw the memo. Johnson's family established the award, which comes with an engraved sword and Luminox Navy SEAL watch.

For Dr. Luis and Aida Destarac, devoted Catholics who immigrated from Guatemala to Texas 30 years ago, the award ceremony was bittersweet, filling them with pride, but also forcing them to confront the reality that due to a rare degenerative optic nerve condition, their son has no need for a fancy Swiss watch.

"We are very emotional," Dr. Destarac said. "He has demonstrated a lot of determination. He is like a superman. A superhero."

"I wish I could donate my eyes to you," Aida said, her own brown eyes welling up with tears as she reached across the table to a son who can no longer see her.

The midshipman first noticed his left-eye vision was blurry in March 2022. He sought testing at Walter Reed Medical Center, and was initially misdiagnosed with optic neuritis. Steroid shots brought no improvement. But over the summer, while he was deployed on a training mission, his right eye also began failing. The realization of how serious the problem was came a bit later, at a particularly poignant moment; Destarac was flying to London for a family wedding, and kept waving to his girlfriend, fellow midshipman Maura Dawson, after she dropped him off at the airport. When Dawson called later, they were both in tears.

"I had walked away, and you kept waving," she said.

"That was a big realization: I couldn't see that well," Destarac recalled. "That was tough."

The official diagnosis was confirmed by genetic testing in August: Destarec had Leber hereditary optic neuropathy, otherwise known as Leber's syndrome. One of his mother's cousin's sons has the same condition, which afflicts about one in every 50,000 people, according to the Cleveland Clinic. The disease affects central vision as if there's a blank space when patients look straight ahead. Although some Leber's patients retain peripheral vision, 95% are legally blind by age 50.

Military medical specialists told Destarac his vision was deteriorating quickly. Some even advised him to leave the academy, "see the sights" while he still could, and rethink how to finish college once he had adapted to vision loss. Another option was to immediately transfer, and given that he was leaving for medical reasons, he'd be exempt from repaying his Naval Academy tuition.

Other schools, Destarac knew, "were going to have a lot more accommodations" for disabled students.

"The third option was to try and ride it out," Destarac said, but if his grades started slipping, and he was kicked out of the academy for failing academically, he would have to pay back his tuition.

Destarac chose to ride it out. He sent his fall professors that I'm-going-blind email and agreed to check in with his battalion officer six weeks into the semester.

"Six weeks in, my grades were really good," Destarac said. "I got the best grades ever this semester and last."

Tran and Ledworth don't take credit for Destarac's success, but they do believe "it took a team effort to lift him across the finish line," Tran said.

When Destarac joined Tran's Naval Architecture and Ocean Engineering class last fall, the instructor immediately went to his department chair for help supporting Destarac. Any special technology devices had to be approved by the provost, as did extensions. Dr. Destarac, a pulmonologist, worked all of his connections back home at the University of Texas at Tyler and found two options to help his son: a pair of magnifying goggles that made Destarac look like he was playing 3D video games in class (he wasn't) and a CCTV magnifying camera that enlarged documents. He was also given double time to complete his exams, and even the provost took a turn serving as an exam proctor.

"It was a collective effort," Tran said.

If there was an award for good attendance at office hours, known as "Extra Instruction" at the Naval Academy, Destarac would win hands down. Often, Tran and his colleagues would use the time to make giant large-print photocopies of important charts and graphs to help him memorize everything from diagrams of ships to principles of thermodynamics.

What Tran said he'll remember most about Alberto isn't his worsening blindness, but his never changing good attitude. "He was so positive in class," the lieutenant said. "He didn't just want to pass, he wanted to do well, and that's what he did. I didn't just teach him; I'm still processing what he taught me."

Despite Destarac's outstanding grades, the U.S. Navy held to a long-standing policy of not accepting a blind service member because he would not be "globally deployable." Destarac said heknew flying helicopters was out, but his Plan B is to become a lawyer, and he would love to have joined the Navy's Judge Advocate General Corps.

"I could definitely do a lot there," Destarac said.

His immigrant parents are especially disappointed that their son won't be commissioned. "It's so strange," Dr. Destarac said. "Why not, when he has a real interest in serving the country?"

Wars these days are not fought "soldier to soldier," Dr. Destarac said, "They are fought computer to computer."

The doctor isn't alone in feeling that his blind son still has much to offer the U.S. Armed Forces. Since 1991, the Baltimore-based National Federation of the Blind has been lobbying to have the armed forces recruit blind service members. Christopher J. Danielsen, a blind lawyer and self-described "Army brat" who serves as director of public affairs for the federation, said Destarac is a poster student for changing the policy.

"It is something that we have long advocated needs to be changed," Danielsen said. "Because there are a lot of talented people who could be serving."

A resolution passed by the federation in 1991 states that failing to "exploit fully the resource of qualified blind persons ... would constitute discriminatory treatment and a denial of their opportunity fully to exercise their rights and responsibilities as first-class citizens."

February's Ship Selection night, when seniors receive their first military assignments, was particularly crushing for Destarac. But he has since rebounded and was excited to celebrate with friends and family at a graduation party on Thursday. His immediate plan is to "take a gap a year" and learn how to be a blind person, from experimenting with technology to considering getting a service dog.

"I don't know how to live on my own," he said. Walking around downtown Annapolis. Destarac cuts an imposing man-in-uniform figure; a 6-foot, 6-inch former swimmer who needs his father's help navigating sidewalks.

"I need to master these things," Destarac said. So, he'll relearn how to walk, take the LSAT, or Law School Admission Test, and go to law school.

"I think it's something I can do pretty well in," he said. "I'm super excited for the next challenge."

(c)2023 The Capital (Annapolis, Md.)

Visit The Capital

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.