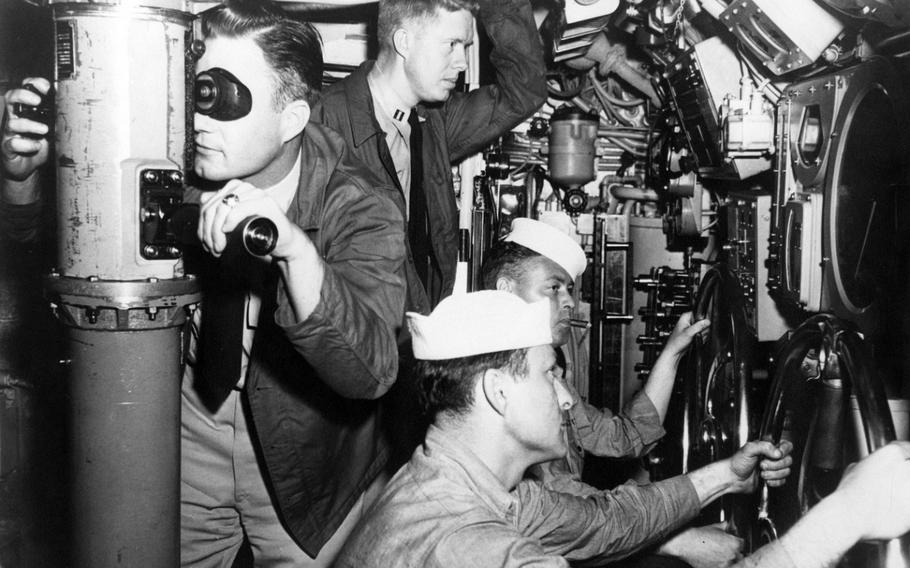

Lt. Jimmy Carter, center top, in the main control room of submarine USS K-1 in 1952. (U.S. Navy)

The world was in the grip of the Cold War in 1952 when a nuclear reactor began melting down.

That reactor, located at Chalk River Laboratories in Ontario, had suffered an explosion on Dec. 12. Radioactive material had escaped into the atmosphere, and millions of gallons of radioactive water flooded into the reactor's basement. Thankfully, no one was injured, but the Canadians needed help to disassemble the reactor's damaged core.

The United States sent 28-year-old Jimmy Carter.

Carter, who entered home hospice care this weekend at 98, is best known for being the nation's 39th commander in chief and oldest living president. But his service to the country began when he was a teenage plebe at the U.S. Naval Academy and continued for four decades after his presidency.

In the years after graduating from Annapolis in 1946, Carter was promoted to lieutenant and took a dangerous assignment aboard a submarine. He was away from his young bride, Rosalynn, and their growing family quite a bit.

It was in these years that President Harry S. Truman desegregated the military. Robert A. Strong, a politics professor at Washington and Lee University, recounts an incident from this period. While his submarine was docked in Bermuda, British military officers invited White members of the American crew to a party. At Carter's urging, the entire crew refused to attend because it was segregated.

In 1952, Carter was selected to join an elite team to help develop the Navy's first nuclear submarines. Once he had trained his crew and the submarine was constructed, Carter was to be the commanding officer of the USS Seawolf, according to Carter in his 1976 book "Why Not the Best?: The First 50 Years."

Then the partial meltdown happened, and Lt. Carter was one of the few people on the planet authorized to go inside a nuclear reactor.

Carter and his two dozen men were sent to Canada to help, along with other Canadian and American service members. Because of the intensity of radiation, a human could spend only 90 seconds in the damaged core, even while wearing protective gear.

First, they constructed an exact duplicate of the reactor nearby. Then they practiced and practiced, dashing into the duplicate "to be sure we had the correct tools and knew exactly how to use them," Carter wrote.

Each time one of his men managed to unscrew a bolt, the same bolt would be removed from the duplicate, and the next man would prep for the next step.

Eventually, it was Carter's turn. He was in a team of three.

"Outfitted with white protective clothes, we descended into the reactor and worked frantically for our allotted time," he wrote.

In 1 minute, 29 seconds, Carter had absorbed the maximum amount of radiation a human can withstand in a year.

The mission was successful. The damaged core was removed. Within two years, it had been rebuilt and was back up and running.

For several months afterward, Carter and his crew submitted fecal and urine samples to test for radioactivity, but "there were no apparent aftereffects from this exposure," Carter wrote, "just a lot of doubtful jokes among ourselves about death versus sterility."

But in an interview with historian Arthur Milnes in 2008, Carter wasn't as cavalier. He said for six months his urine tested positive for radioactivity.

"They let us get probably a thousand times more radiation than they would now," he said. "It was in the early stages, and they didn't know."

Carter returned to preparing to command a nuclear submarine, but soon, fate intervened. In July 1953, Carter's father Earl died of pancreatic cancer at 58. (In fact, pancreatic cancer would eventually kill his mother and all three of his siblings.)

As the eldest child, Carter sought an immediate release from the Navy to take over the family business. After seven years of service, he was honorably discharged on Oct. 9, 1953.

The incident had a lifelong impact on Carter's views on nuclear power, Carter biographer Peter Bourne told Milnes. As a young naval officer, he had approached it in a "very scientific and dispassionate way," Bourne said, but Chalk River showed him its power to destroy.

"I believe this emotional recognition of the true nature of the power mankind had unleashed informed his decisions as president," Bourne said, "not just in terms of having his finger on the nuclear button, but in his decision not to pursue the development of the neutron bomb as a weapon."