Army Brig. Gen. Lance Okamura, deputy commander for Joint Task Force-Red Hill, poses at his headquarters on Ford Island, Hawaii, Jan. 4, 2023. (Wyatt Olson/Stars and Stripes)

FORD ISLAND, Hawaii — Brig. Gen. Lance Okamura’s Army career spans 30 years, from enlisted soldier to officer, the Pacific Ocean to Afghanistan, military policing to counterterrorism.

For all that, though, the Hawaii native is adamant that his last job — overseeing Guantanamo prison — best qualifies him for his new role. As deputy commander for Joint Task Force-Red Hill at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, Hawaii, Okamura is responsible for community outreach and, in part, repairing the lines of communication between the Navy and the surrounding community.

Joint Task Force-Red Hill is charged with safely emptying the roughly 104 million gallons of fuel from the World War II-era Red Hill underground storage facility, which is operated by the U.S. Navy. The tanks near Pearl Harbor leaked fuel into the surrounding area, causing widespread groundwater contamination discovered in November 2021 that affected nearby military housing areas.

Shortly before arriving in Hawaii in late November, Okamura spent about two years as deputy commander and then as commander of Joint Task Force-Guantanamo in Cuba overseeing the military prison that holds detainees amassed as part of America’s Global War on Terror launched in the wake of the 9/11 attacks.

“I did three important things that I focused my energies on,” Okamura, 52, said during an interview Wednesday at the headquarters of Joint Task Force-Red Hill on Ford Island, Hawaii.

“I had to solve complex problems,” he said. “I had to shape the future. And then, No. 3, engage with communities of interest.”

In Guantanamo that meant dealing with the complex and seemingly insurmountable goal of emptying and closing the prison while at the same time being restricted from transferring any prisoners to the United States.

A Navy contractor conducts a three-dimensional scan to confirm structural integrity of fuel pipes at the Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility in Halawa, Hawaii, Dec. 20, 2022, as part of the two-year project to empty the tanks. (Luke Cohen/U.S. Marine Corps)

Public backlash

In March, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin ordered the Red Hill facility in Hawaii permanently closed after a jet fuel leak contaminated one of three wells used by the Navy for delivering water to Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam and myriad homes in nearby military communities.

Thousands of residents were temporarily relocated to Waikiki Beach hotels in early 2022 as the Navy isolated the contaminated well and flushed water mains and pipes in homes.

More than 100 individuals have sued the Navy for compensation for conditions and illnesses they say arise from exposure to fuel-tainted water.

The task force is overseeing extensive repairs of the facility’s piping and safety systems to meet its target of complete defueling by summer 2024.

Okamura’s job focuses on the second part of the task force’s mission statement, which is “to rebuild trust with the State of Hawaii and the local community of Oahu.”

“The burden of making sure that I am able to rebuild that faith and confidence in the military with the community is my responsibility to bear,” he said. “And so, when I take a look at it, my instinct is, in simple terms, to make sure that all community stakeholders from the local-state level all the way up to the federal and congressional level, have faith and confidence in JTF-Red Hill. That’s No. 1, that we're doing the right thing for the right reason.

“No. 2, that we're going to be transparent, open and communicative, especially in providing information and receiving that information back from them,” he said.

“And No. 3, which is really important, is making sure that we're consistent in our messaging.”

Moderating the public backlash arising from the Red Hill contamination — discovered in drinking water in November 2021 — will not be easy after events of the past year.

Navy officials were initially skeptical of complaints by residents of malodorous water.

Capt. Erik Spitzer, then the commander of Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, told residents that the water was safe and that he and his staff were drinking it.

Many residents complained that even after initial testing found indications of fuel contamination, the Navy was piecemeal in notifying those potentially affected.

Even after the Navy took responsibility for the contamination and for its remediation, it balked at the Hawaii Department of Health’s emergency order directing the facility be permanently closed.

Local groups, such as Sierra Club of Hawaii and Oahu Water Protectors, are critical of the Navy’s handling of the contamination and the plans for emptying and closing the facility.

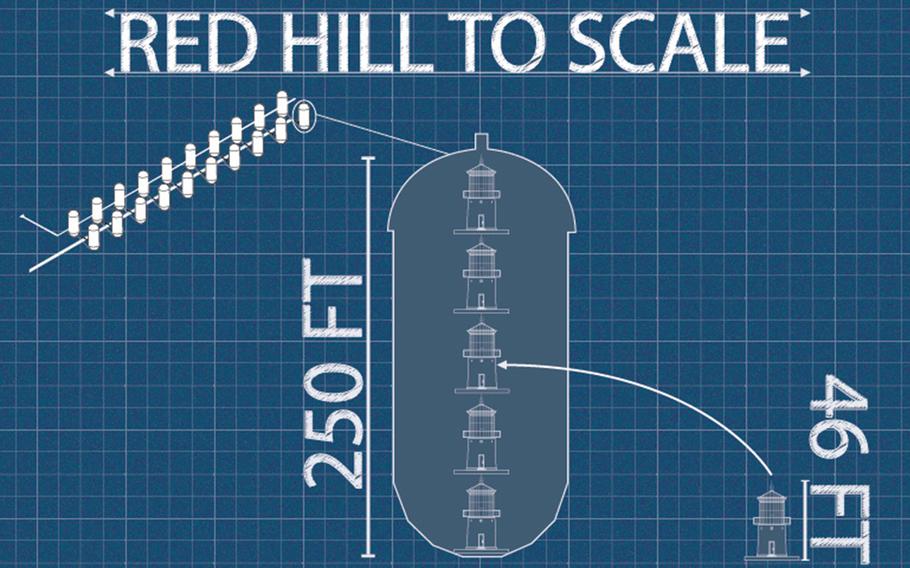

A graphic created by Joint Task Force Red-Hill depicts the size and scale of the massive underground tanks at the Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility in Hawaii by comparing a single tank to the Makapu’u Point Lighthouse, a popular tourist site on Oahu. (Luke Cohen/U.S. Marine Corps)

Oahu born

In late November, Joint Task Force-Red Hill officials temporarily delayed emptying the tanks as workers cleaned up a spill of roughly 1,100 gallons toxic firefighting foam at the facility.

Several Facebook groups, particularly JBPHH Water Contamination Support, contain a litany of posts by residents and former residents of the affected communities cataloging illnesses, anguish and financial hardships they say arise from the tainted water. Some posters complain that their tap water at times still exhibits an unpleasant sheen.

Some complaints and criticism are beyond the purview of Joint Task Force-Red Hill, but ultimately Okamura must deal with all public perception when it comes to Red Hill.

Born and raised on Oahu in a military family — his father was in the Air Force — Okamura said his deep understanding of Hawaiian culture is an advantage in community outreach.

Because his mother was of Hawaiian descent, Okamura was eligible to attend Kamehameha Schools, which was established and endowed in the late 1800s from a bequest by Hawaiian Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop.

Attending the schools provided him “the cultural understanding of what Native Hawaiians really care about,” Okamura said, which he summarized in three tenets.

“Land is home,” he said. “Land is not a thing to the Hawaiian people. We receive a lot of blessings through land.

“Water is life. It provides a sustenance of all living things here in the state of Hawaii.”

And third is the people. “Hawaiians are very focused on people, the spirit of aloha, the spirit of love, the spirit of community,” he said.

“So, I think my background understanding of land, water and people helps provide greater understanding to the folks I work with in Department of Defense on the topic of mutual stewardship,” he said.

“Stewardship is not just owning a thing or being responsible for a thing,” Okamura said. It means accountability and working together to benefit land, water and people.

“Because, in Hawaiian history, the Hawaiian people just didn't take from the land, they cultivated the land, they cultivated the environment, knowing full well that every object has a living spirit in it because it provides benefits to people.”

Okamura acknowledged “there’s a lot of folks who don’t want to see the military’s presence here,” while others remain robust advocates.

It is a “very complex” mixture of people with whom he needs to figure out how best to engage, he said.

“I have to shape the future,” he said.