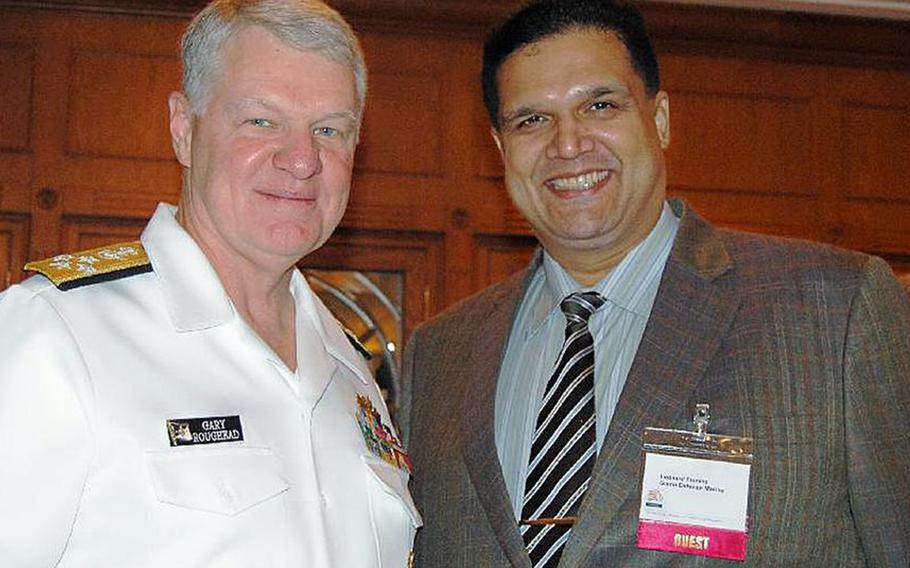

In this undated photo, former Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Gary Roughead poses with Leonard Glenn Francis, also known as "Fat Leonard," who admitted to bribing Navy officials with cash, luxury travel and prostitutes for classified or inside information that benefited his firm. Roughead was not implicated in the case. (Navy League of the United States)

SAN DIEGO (Tribune News Service) — For the past several years, Leonard Glenn Francis — the figure at the center of the Navy’s worst corruption scandal in modern history — has been under house arrest in San Diego, eschewing interview requests and biding his time until his role as government cooperator is over.

Now, for reasons that aren’t entirely clear, Francis has opened the floodgates.

He secretly recorded a podcast with a Singapore-based journalist, offering for the first time publicly his own account of the bribery scandal that has rocked the Navy, led to the prosecution of dozens of military officials and put hundreds more under scrutiny.

The nine-part podcast, which began releasing episodes Oct. 4, came as a shock to many people involved in the ongoing case. It has also put attorneys on edge with the blockbuster criminal trial of six naval officers in San Diego — and Francis’ anticipated debut on the stand as a star witness for the prosecution — just a few months away. (An attorney indicated last week in court that a seventh officer will be pleading guilty before trial.)

On Thursday, the San Diego federal judge overseeing the case authorized the defense team to subpoena New York-based podcast production company Audiation for all recordings from the project. Audiation, which partnered on the podcast with Project Brazen and PRX, did not respond to the Union-Tribune’s request for comment.

With the last episode expected to air this week and trial looming, defense attorneys for the naval officers declined to comment on the podcast or any of the statements made by Francis, who pleaded guilty in 2015 and has yet to be sentenced. The U.S. attorney’s office also declined to comment.

It is unclear how this latest development might reshape the case.

The podcast, titled “Fat Leonard,” is a nod to Francis’ imposing physique and longtime nickname in military circles in ports across Southeast Asia.

It partly repackages what has become a familiar set of facts, detailing how Francis bribed Navy officials with lavish gifts, five-star resort stays, gourmet dinners and the services of prostitutes in exchange for confidential military information to gain a competitive edge for his business, Glenn Defense Marine Asia. His ship-husbanding company supplied Navy ships with security, water, trash removal and other supplies — services for which he frequently overbilled. He’s admitted to cheating the Navy out of at least $35 million.

For those who have been closely following the ongoing legal saga, the podcast offers some new revelations, including that Francis kept sex videotapes of Navy officers with prostitutes, that he lives with his three Malaysian children while under house arrest and that Chinese spies may have hacked into his trove of secrets just before his arrest.

In the recorded interviews with former Wall Street Journal reporter Tom Wright, Francis at times exudes the charisma and command that gained him access to the Navy’s top brass, as well as the street cred that earned him the respect of the lower ranks. At other times during the podcast, Francis’ voice is raspy and a bit labored, hinting at the battle with cancer he’s been waging.

He nonchalantly justifies those sex tapes, which he claims to still have boxed up in storage: “I’m not making porn. It’s always great to see people when they’re drunk, what they’re capable of doing. … I kept it more for entertainment.”

He brags about the command he held as a civilian over the Navy’s 7th Fleet: “Everybody was in my pocket. I had them in my hand, rolling them around.”

And he complains about being singled out as the story’s villain: “I’ve done a lot for the last 30 years, supporting hundreds if not thousands of ships, hundreds of thousands of sailors and Marines, in all kinds of places. I never brought any harm to the United States. This was just financial matter. It was not me hurting anybody.”

One thing Francis hasn’t offered in the podcast: remorse.

Since Francis’ arrest in a San Diego hotel room in 2013, numerous media outlets have asked for — and been denied — interviews, including the Union-Tribune.

But Francis last year apparently began shopping around for someone to tell his life story.

Wright and another former Wall Street Journal colleague, Bradley Hope, had just authored the book “Billion Dollar Whale” about a massive fraud against the Malaysian government, and the reporting partners were looking for a project for their new journalism studio and production company, Project Brazen.

A source from the book who also knew Francis offered to put Wright in touch.

“I don’t believe Leonard talked to his lawyers at all about his decision to talk to me,” Wright said in a recent interview with the Union-Tribune from his home in Singapore.

The podcast asserts that Francis was prohibited from speaking as part of his plea agreement. However, nothing in the plea document filed publicly with the court prohibits him from speaking with the media or talking about the case in general.

Francis’ San Diego-based defense attorney Devin Burstein declined to answer several questions posed by the Union-Tribune, citing attorney-client privilege and the ongoing case. But he confirmed that Francis’ decision to participate in the podcast “has no effect whatsoever on his plea agreement.”

Even now, Wright said Francis’ motivation for talking remains somewhat of a mystery, given the pending trial and uncertainty of his own sentence. He faces up to 25 years in prison.

“Maybe it’s megalomania, or partly boredom,” Wright said. “I think he’s trying to drop a neutron bomb on the Navy.”

Pulling off the podcast would have been extremely unlikely if Francis had been in a federal lockup. Phone access is iffy, depending on the detention center, and the audio quality would have been poor for a podcast anyway. In-person visits would have been out of the question during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Francis had been initially detained upon arrest, after a judge found him to be a flight risk, but he was later released on medical furlough as his health declined.

He lives in an apartment in an undisclosed location and is monitored by a GPS bracelet. Burstein said Francis is living “under very stringent conditions approved by the court” but declined to provide specifics that have been spelled out in sealed court filings.

To equip Francis for the podcast, the production team sent a high-quality microphone to a person who delivers Francis supplies. With a makeshift studio in place, Wright and Francis spent hours talking long-distance over a podcasting app, from February to September.

Francis frequently shifts between braggadocious storytelling and an insistence that the Navy is ultimately to blame for unofficially sanctioning a corrupt system.

Through his interviews, Francis characterizes himself as a scapegoat betrayed by the Navy — an institution that has long depended on local contractors like him to be a buffer in foreign ports and get the job done, even if the means are less than savory.

Kickbacks and corruption are just part of the game, and everyone knows it, he argues.

“It’s a huge risk for me to do what I’m doing,” Francis tells Wright of his decision to do the podcast. “But I’m so upset that I’m portrayed as the bad guy when I’m not the bad guy. I’ve done everything they wanted me to do.”

The podcast, which is interwoven with interviews of Navy whistleblowers, addresses the Navy’s unwillingness early on to rein in Francis despite several red flags, as well as to correct a culture of misogyny among the ranks that continues to fester long after the Tailhook sexual misconduct scandal of the early 1990s.

The podcast also looks at the fallout of the current investigation and points to high-ranking officials who were not disciplined — and even promoted — despite Francis’ claims of bribing them. Many of those accused officials have adamantly denied any inappropriate interactions with Francis or his company.

A Pentagon spokesperson declined to comment on the podcast, citing the ongoing case.

While Francis insists he remained loyal to the United States, Wright suggests the national security threat of a foreign contractor compromising so many military personnel was greater than has been publicly acknowledged.

Francis admits to being courted by Chinese and Russian diplomats in Singapore. And later, as Francis became aware of the U.S. investigation closing in on him, he moved his files — records that potentially included U.S. military secrets — to a Chinese server. That server was hacked by the Chinese government, the podcast’s final episode will report, according to Wright.

Wright said he, like many who have interacted with Francis before him, was at first charmed by the big personality. But the journalist also struck a nerve as he continued to dig into Francis’ personal life and questioned his views on women.

The tenor between host and interviewee takes a sharp turn at Episode 6, as Wright accuses Francis of being a misogynist.

In the episode, Wright interviews one of Francis’ former mistresses — the mother of two of his children — who says Francis became jealous and abruptly dropped her from his life and kept her from her children. Francis’ mother took the children from Singapore to Kuala Lumpur in 2013 when they were very young, and the children’s mother hasn’t seen them since or known of their whereabouts, despite two orders from foreign courts designating her as custodian, she says.

At some point, the children, along with a child from another woman, came to live with Francis in San Diego while he remains under house arrest. “Everybody came legally,” Francis says in the podcast.

He says “Uncle Sam” knows what he’s doing, and suggests the U.S. government has allowed the children to live with him as a perk for his cooperation in the investigation. Burstein said that is “outright false.”

Francis says the children are thriving in San Diego, but he grows increasingly angry as Wright challenges him about their mother.

“I did not kidnap the kids. They were all just mistresses, and my children were legally born and they had my name and they are Malaysian citizens,” he tells Wright.

The State Department, the agency that issues visas, said it does not provide information on visa holders when the Union-Tribune asked about what kind of visas the children have and if they were issued before or after Francis’ arrest.

That conversation was the last between Wright and Francis.

Burstein would not disclose how his client feels about the final product, but the lawyer offered his personal opinion: “I think it lacks objectivity. I think it’s more hit piece than true journalism.”

The story Wright ultimately told was likely not the one Francis had imagined, as the journalist honed in on the women affected — from Tailhook’s victims to the sex workers to the Navy wives to the mother of Francis’ children.

“I see the whole podcast as a study of misogyny,” Wright said. “He’s been arrested for white collar crimes, but when it comes to the collateral damage caused by his actions — the women in this story — there has been no justice.”

©2021 The San Diego Union-Tribune.

Visit sandiegouniontribune.com.

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.