Marines train on the Ares Company’s Multi-Purpose Anti-Armor Anti-Personnel Weapons System range. (Sarah L. Voisin/The Washington Post)

POHAKULOA TRAINING RANGE, Hawaii — The Marine gunner knelt on the rocky red soil of a 6,000-foot-high volcanic plain. He positioned the rocket launcher on his shoulder, focused the sites on his target, a rusted armored vehicle 400 yards away, and fired.

Two seconds later a BANG.

“Perfect hit,” said his platoon commander.

The gunner, 23-year-old Lance Cpl. Caden Ehrhardt, is a member of the 3rd Marine Littoral Regiment, a new formation that reflects the military’s latest concept for fighting adversaries like China from remote, strategic islands in the western Pacific. These units are designed to be smaller, lighter, more mobile — and, their leaders argue, more lethal. Coming out of 20 years of land combat in the Middle East, the Marines are striving to adapt to a maritime fight that could play out across thousands of miles of islands and coastline in Asia.

Instead of launching traditional amphibious assaults, these nimbler groups are intended as an enabler for a larger joint force. Their role is to gather intelligence and target data and share it quickly — as well as occasionally sink ships with medium-range missiles — to help the Pacific Fleet and Air Force repel aggression against the United States and allies and partners like Taiwan, Japan and the Philippines.

These new regiments are envisioned as one piece of a broader strategy to synchronize the operations of U.S. soldiers, sailors, Marines and airmen, and in turn with the militaries of allies and partners in the Pacific. Their focus is a crucial stretch of territory sweeping from Japan to Indonesia and known as the First Island Chain. China sees this region, which encompasses an area about half the size of the contiguous United States, as within its sphere of influence.

The overall strategy holds promise, analysts say. But it faces significant hurdles, especially if war were to break out: logistical challenges in a vast maritime region, timely delivery of equipment and new technologies complicated by budget battles in Congress, an overstressed defense industry, and uncertainty over whether regional partners like Japan would allow U.S. forces to fight from their islands. That last piece is key. Beijing sees the U.S. strategy of deepening security alliances in the Pacific as escalatory — which unnerves some officials in partner nations, who fear that they could get drawn into a conflict between the two powers.

The stakes have never been higher.

Marines from the 3d Littoral Combat Team train on tube-launched, optically tracked, wire-guided missiles or TOW missile system in Hawaii in January. (Sarah L. Voisin/The Washington Post)

Beijing’s aggressive military modernization and investment over the past two decades have challenged U.S. ability to control the seas and skies in any conflict in the western Pacific. China has vastly expanded its reach in the Pacific, building artificial islands for military outposts in the South China Sea and seeking to expand bases in the Indian and Pacific Oceans — including a naval facility in Cambodia that U.S. intelligence says is for exclusive use by the People’s Liberation Army.

China not only has the region’s largest army, navy and air force, but also home-field advantage. It has about 1 million troops, more than 3,000 aircraft, and upward of 300 vessels in proximity to any potential battle. Meanwhile, U.S. ships and planes must travel thousands of miles, or rely on the goodwill of allies to station troops and weapons. The PLA also has orders of magnitude more ground-based, long-range missiles than the U.S. military.

Taiwan, a close U.S. partner, is most directly in the crosshairs. President Xi Jinping has promised to reunite, by force if necessary, the self-governing island with mainland China. A successful invasion would not only result in widespread death and destruction in Taiwan, but also have catastrophic economic consequences due to disruption of the world’s most advanced semiconductor industry and of maritime traffic in some of the world’s busiest sea lanes — the Taiwan Strait and the South China Sea. That would create enormous uncertainty for businesses and consumers around the world.

“We’ve spent most of the last 20 years looking at a terrorist adversary that wasn’t exquisitely armed, that didn’t have access to the full breadth of national power,” said Col. John Lehane, the 3rd Marine Littoral Regiment’s commander. “And now we’ve got to reorient our formations onto someone that might have that capability.”

The U.S. Marine Corps has a blueprint to fight back: a vision called Force Design that stresses the forward deployment of Marines — placing units on the front line — while making them as invisible as possible to radar and other electronic detection. The idea is to use these “stand-in” forces, up to thousands in theater at any one time, to enable the larger joint force to deploy its collective might against a major foe.

The aspiration is for the new formation to be first on the ground in a conflict, where it can gather information to send coordinates to an Air Force B-1 bomber so it can fire a missile at a Chinese frigate hundreds of miles away or send target data to a Philippine counterpart that can aim a cruise missile at a destroyer in the contested South China Sea.

The reality of the mission is daunting, experts say.

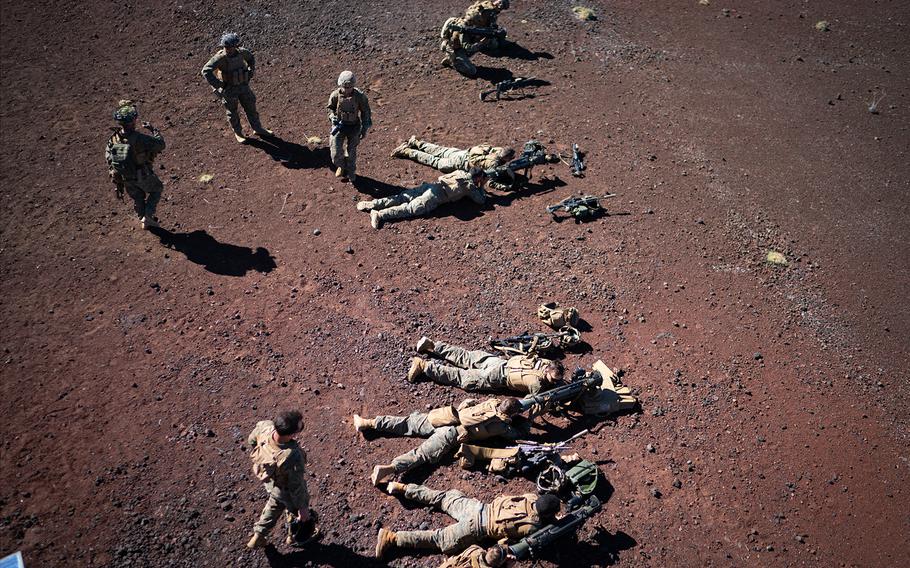

Marines participate in training exercises at the Pohakuloa Training Range. (Sarah L. Voisin/The Washington Post)

Even if you get Marines into these remote locations, “resupplying them over time is something that needs to be rehearsed and practiced repeatedly in simulated combat conditions,” said Colin Smith, a RAND researcher formerly with I Marine Expeditionary Force, whose area of responsibility includes the Pacific. “Just because you can move it in peacetime doesn’t mean you’ll be able to in warfare, especially over long periods of time.”

Though the Marines are no longer weighed down by tanks, the new unit’s Littoral Combat Team, an infantry battalion, will be operating advanced weapons that can fire missiles at enemy ships up to 100 nautical miles away to help deny an enemy access to key maritime chokepoints, such as the Taiwan and Luzon straits. By October, each Marine Littoral Regiment will have 18 Rogue NMESIS unmanned truck-based launchers capable of firing two naval strike missiles at a time.

But a single naval strike missile weighs 2,200 pounds, and resupplying these weapons in austere islands without runways requires watercraft, which move slowly, or helicopters, which can carry only a limited quantity at a time.

“You’re not very lethal with just two missiles, so you’ve got to have a whole bunch at the ready and that’s a lot more stuff to hide, which means your ability to move unpredictably goes down,’’ said Ivan Kanapathy, a Marine veteran with three deployments in the western Pacific. “There’s a trade-off between lethality and mobility — mobility being a huge part of survivability in this environment.”

Though NMESIS vehicles radiate heat, and radar emits signals that can be detected, the Marines try to lower their profile by spacing out the vehicles, camouflaging them and moving them frequently, as well as communicating only intermittently. Similar tactics are being tested by Ukrainian troops on the battlefield, where despite the number of Russian sensors and drones, “if you disperse and conceal yourself, it’s possible to survive,” said Stacie Pettyjohn, director of the defense program at the Center for a New American Security.

But on smaller islands, there are fewer areas to hide, fewer road networks to move around on, “so it’s easier for China to search and eventually find what they’re looking for,” she said.

Lehane, the unit’s commander, says that the unit’s most valuable role isn’t conducting lethal strikes; it is the ability to “see things in the battlespace, get targeting data, make sense out of what is going on when maybe other people can’t.” That’s because the Pentagon expects, in a potential war with China, that U.S. satellites will be jammed or destroyed and ships’ computer networks disrupted.

China now has many more sensors — radar, sonar, satellites, electronic signals collection — in the South China Sea than the United States. That gives Beijing a formidable targeting advantage, said Gregory Poling, an expert on Southeast Asia security at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “The United States would have to expend an unacceptable amount of ordnance to degrade those capabilities to blind China,” he said.

Marines train on the Ares Company’s Multi-Purpose Anti-Armor Anti-Personnel Weapons System (MAAWS) range. (Sarah L. Voisin/The Washington Post)

The unit has been practicing techniques to communicate quietly. In a bare room of a cinder block building at its home base in Kaneohe, Hawaii, Marines in the regiment’s command operations center tapped on laptops on portable tables, plastic sheets taped over the windows. In the field, the gear could be set up in a tent, packed up and moved at a moment’s notice. Intelligence analysts, some of whom speak Mandarin, were feeding information to commanders on the range at Pohakuloa, practicing connections between the command on Oahu and the infantry battalion on the Big Island.

But exercises are not real life. Indo-Pacific Command is striving to build a Joint Fires Network that will reliably connect sensors, shooters and decision-makers in the Army, Navy, Marines and Air Force. But chronic budget shortfalls, and long-standing friction between the combatant commands and the services — each of which decides independently of the commands what hardware and software to buy — have slowed development.

Even when it is fully fielded, Pettyjohn said, “the question is, is this network going to be survivable in a contested electromagnetic space? You’re going to have a lot of jamming going on.”

Last April, the Marines and the rest of the Joint Force tested the new warfighting concept with their Philippine partner in a sprawling, weeks-long exercise — Balikatan — which in Tagalog means “shoulder-to-shoulder.”

With a command post on the northwestern Philippine island of Luzon, the regiment’s infantry battalion and Philippine Marine Corps’ Coastal Defense Regiment rehearsed air assaults and airfield seizures to gain island footholds, which would then be used as bases from which to gather intelligence and call in strikes.

During one live-fire exercise, the 3rd MLR helped the larger U.S. 3rd Marine Division glean location data on a target vessel — a decommissioned World War II-era Philippine ship — which U.S. and Philippine joint forces promptly sunk. Soon, the Philippine Coastal Defense Regiment expects to be able to fire its own missiles, said Col. Gieram Aragones, the regiment’s commander, in an interview from his headquarters in Manila.

“Our U.S. Marine brothers have been very helpful to us,” Aragones said. “They’ve guided us during our crawl phase. We’re trying to walk now.”

The training goes both ways. The Philippine Marines taught their American counterparts survival skills, like finding and purifying water from bamboo, and cooking pigs and goats in the jungle.

Marines train at a firing range in January. (Sarah L. Voisin/The Washington Post)

China in recent years has intensified its harassment of Philippine fishing and Coast Guard vessels. As recently as Saturday, Chinese Coast Guard ships fired water cannons at a Philippine boat conducting a lawful resupply mission to a Philippine military outpost at a contested shoal in the South China Sea. Amid such provocations, Manila has stepped up its defense partnership with the United States. A year ago, Manila announced it was granting its longtime ally access to four new military bases.

Although the two countries are treaty allies, bound to come to each other’s defense in an armed attack in the Pacific, how far Manila will go to support U.S. operations in a Taiwan conflict is an open question, said CSIS’s Poling. “Part of the reason for all the military training, the tabletop exercises, and all these new dialogues taking place is feeling out the answer,” he said.

Aragones said it’s important for the United States and the Philippines to jointly strengthen deterrence. “This is not only an issue for the Philippines,” he said. “It’s an issue for all countries whose vessels pass through this body of water [the Chinese are] trying to claim.”

Some 800 miles to the north, the Marines’ newest unit, the 12th Marine Littoral Regiment, was created in November. It was formed by repurposing the 12th Marine Regiment based in Okinawa, already home to a large concentration of U.S. military personnel in Japan — a source of tension with local communities dating back decades.

This unit is intended to operate out of the islands southwest of Okinawa, the closest of which are less than 100 miles from Taiwan. Over the years, Tokyo has shifted its military focus away from northern Japan, where the Cold War threat was a Soviet land invasion, to its southwest islands.

Recent events have vindicated that shift in Tokyo’s eyes. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and China’s bellicose response to then-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan in August 2022 — in which the PLA fired five ballistic missiles into waters near Okinawa — rattled Japan. The number of days that Chinese Coast Guard vessels sailed near the Senkaku Islands, which are administered by Japan but claimed by China, reached a record high last year.

As a result, in the last year and a half, Tokyo has announced a dramatic hike in defense spending and deepened its security partnership with the United States, Philippines and Australia. Washington hailed Japan’s endorsement of the new U.S. Marine unit’s positioning in the Southwest Islands last year as a significant advance in allied force posture.

But resentment toward U.S. troops lingers in Okinawa, rooted primarily in the disproportionate burden of hosting a major U.S. military presence. The prefecture is home to half of U.S. military personnel in Japan, while making up less than 1% of Japan’s land mass.

“We are concerned about rising tensions with China and the concentration of U.S. military” on Okinawa and the Japanese military buildup in the area, said Kazuyuki Nakazato, director of the Okinawa Prefecture Office in Washington. “Many Okinawan people fear that if a conflict happens, Okinawa will easily become a target.”

He argued the best way to defuse the tension is for Tokyo to deepen diplomacy and dialogue with China, not military deterrence alone.

Other local officials are more receptive to a U.S. presence, arguing that Japan alone cannot deter China. “We have no choice but to strengthen our alliance with the U.S. military,” said Itokazu Kenichi, mayor of Yonaguni town on the island of the same name, the westernmost inhabited Japanese island — just 68 miles from Taiwan.

Japan’s Self-Defense Forces has begun to establish a presence on the islands, including a surveillance station on Yonaguni, where they conducted joint exercises with other U.S. Marines last month, an interaction that has begun to accustom residents to the Marines, Kenichi said.

Ultimately, how much latitude to allow the Marines will be a political decision by the prime minister and the Diet, Japan’s parliament.

On the range at Pohakuloa, Hawaii, the littoral combat team trained for a month. They flew Skydio surveillance drones over a distant hill. They practiced machine gun and sniper skills.

As the wind howled on a lava rock bluff one morning, Lt. Col. Mark Lenzi surveyed his gunners firing wire-guided missiles at targets 1,200 yards away. Lenzi, who served in Iraq and Afghanistan, said what’s different in the Pacific is that Marines won’t be fighting insurgents directly, but will be assigned to enable others to beat back the enemy.

“It takes the whole joint force” to deter in the Pacific, he said. “We train joint. We fight joint.”

These new forces will be at the heart of the “kill web,” he said, referring to the mix of air, sea, land, space and cyber capabilities whose efficient syncing is crucial if it comes to a battle over Taiwan.

“This one unit alone is not going to save the world,” said Col. Carrie Batson, chief of strategic communications for the Pacific Marines. “But it’s going to be vital in this fight, if it ever comes.”

Regine Cabato in Manila and Julia Mio Inuma in Tokyo contributed to this report.