Approximately a third of Guam, pictured here on Dec. 10, 2022, is covered by unique limestone forests. (Alex Wilson/Stars and Stripes)

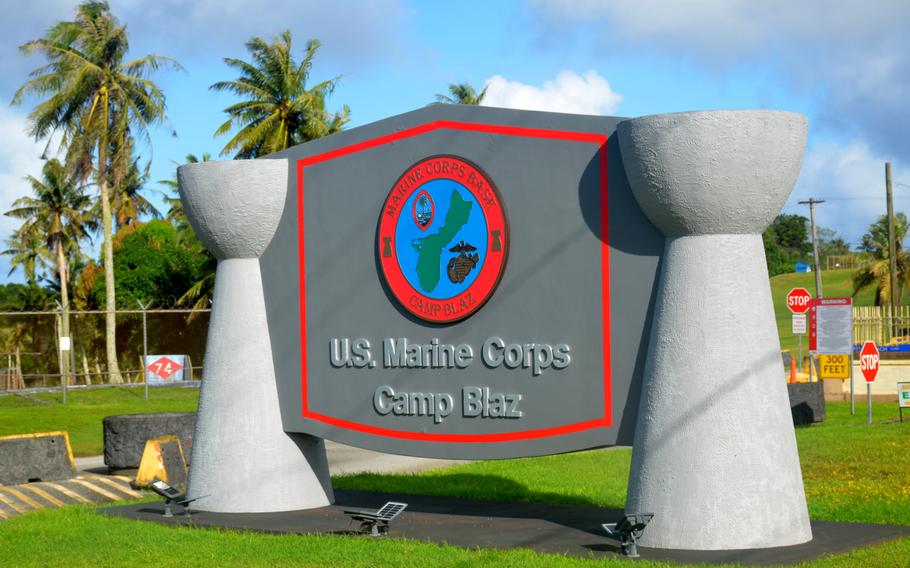

Already unhappy that construction of the Marine Corps’ Camp Blaz disturbed cultural and ecological sites on Guam, some local leaders are wary of a proposed missile-defense system that could damage more island heritage.

In the global power competition with China, the United States views Guam as a power platform and military logistics center that provides a waypoint for aircraft and ships moving between the two hemispheres.

But many Chamorros – indigenous natives of Guam – are worried about further erosion of their homeland as the military beefs up its presence, including the planned influx of 5,000 Marines to Blaz.

“Of course, you can visually see the changing of the landscape,” Robert Underwood, a former Guam delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives and chairman of the Pacific Center for Island Security, told Stars and Stripes by phone May 5. “On top of that is, of course, the digging up of the cultural resources and ancient tribal lands.”

Blaz, a 4,000-acre installation west of Andersen Air Force Base, has already destroyed 1,000 acres of the island’s distinctive limestone forest.

The forests, home to several unique species, are tropical woodlands rooted in thin soils on limestone formed from ancient coral reefs. About 33% of Guam is covered by these forests, according to the online Guampedia.

The base’s construction also revealed numerous Chamorro burial sites and other archaeological remains.

Approximately a third of Guam, pictured here on Dec. 10, 2022, is covered by unique limestone forests. (Alex Wilson/Stars and Stripes)

Next up: Missile defense

Blaz officially opened in January. By March, the Defense Department proposed building the Enhanced Integrated Air and Missile Defense System, for which environmental surveys and public hearings are underway.

A draft of the project’s environmental impact statement is expected in spring 2024, according to a factsheet released by the Missile Defense Agency.

The system, designed to detect and destroy incoming missiles from any direction, may pose similar problems for Guam, Underwood said.

The project includes at least 20 proposed construction sites where mobile defense batteries would rotate across the 210-square-mile island. Most are on government property, but the project may require privately owned real estate, too.

Noting the public’s disapproval of how Blaz was handled, Underwood said he was skeptical of how receptive it will be to the new project, especially without knowing its details.

“All of those issues are on the table,” he said. “It seems to me that if you’re really going to do an environmental impact statement or start the process of reviewing it, you really have to explain what it is you’re actually doing.”

Melvin Won Pat-Borja, executive director of Guam's Commission on Decolonization, pictured here on Dec. 7, 2022, is critical of military expansion on the island. (Alex Wilson/Stars and Stripes)

During construction, Blaz officials made efforts to preserve the island’s resources, but they seemed to be just formalities, said Underwood and Melvin Won Pat-Borja, executive director for Guam’s Commission on Decolonization.

“The manner in which all of that has been carried out has been not as open as it can be,” Underwood said. “I think they’ve just gone through the required steps.”

Portions of Blaz are also situated on what was likely an ancient village, with discoveries of burial sites, tools and structures, Won Pat-Borja told Stars and Stripes in December.

“That was one of the major contentions from the local community, was that as they started to make more discoveries, it was pretty clear they were dealing with a settlement,” he said.

Many Chamorros are worried about further erosion of their homeland as the military beefs up its presence, including the planned influx of 5,000 Marines to Camp Blaz. (Alex Wilson/Stars and Stripes)

‘Highly influential’

Managers on the Blaz project disagreed with the critics.

Construction did level acres of limestone forest, one of the island’s “most threatened habitats,” but the base is also restoring an equal amount of woodlands elsewhere, Adrienne Loerzel, Blaz’ forest enhancement program manager, told Stars and Stripes by phone April 25.

Chamorro burial mounds found on the construction site were left in place after the community “overwhelmingly” requested it. Some sites are planned to be designated as cultural markers, open to the public and to educate visitors about Chamorro history, said Albert Borja, Blaz’ environmental director.

He objected to the view that the base’s efforts were just a formality. He pointed public input on decisions like the location of the Blaz firing ranges.

Ronnie Rogers, lead archeaologist for Marine Corps Camp Blaz, Guam, discusses a Chamorro burial mound discovered during the base's construction, Dec. 9, 2022. (Alex Wilson/Stars and Stripes)

“I would disagree with folks that say that the people of Guam or its elected leaders are powerless in these processes; they are highly influential,” Borja said.

Blaz’ lead archaeologist, Ronnie Rogers, agreed. Every construction project requires public notice and “every action that we take” takes consultation and public comments into consideration, he said.

“We respond to each of those, whether it comes from the public or the historic preservation officer,” he told Stars and Stripes by phone April 25. “Those that have comments that are productive, we try to implement those recommendations where we can.”