Marine Corps Maj. Gen. Joseph F. Shrader, center, the commanding general of Marine Corps Logistics Command, and Capt. Benjamin Leichty, right, join David R. Clifton, the executive deputy of the command, in front of the newly unveiled Route 66 Eagle, Globe and Anchor monument at Marine Corps Logistics Base Barstow, Calif., on Oct. 22, 2021. The monument was dedicated Nov. 9. (Jack J. Adamyk/U.S. Marine Corps)

There’s a Marine Corps logistics base in California’s high desert outside Barstow where the service’s Eagle, Globe and Anchor looks unlike those in any other clime or place.

The symbol, made up of a highway shield superimposed over the service’s emblem, is found on signs lining the shoulder of Joseph L. Boll Avenue, an original part of U.S. Highway 66 at Marine Corps Logistics Base Barstow.

The modified emblem recognizes the road’s ties to the logistics hub, which “has the privilege of being the only military base that has Route 66 running straight through it,” said Jason Thompson, the installation’s environmental director, who oversees its historical preservation program, in an email this week.

The road section has been off-limits to the public since 1964, after Interstate 40 was built. But officials who get their kicks from preserving history came up with the emblem redesign in 2019 to bring more attention to it as a cultural resource.

It’s also painted in large stencils on the pavement of that 1.7-mile stretch of road, which passes the commissary and Leatherneck Lanes bowling alley.

Marine Corps Maj. Gen. Joseph F. Shrader, the commanding general of Marine Corps Logistics Command, and David R. Clifton, the command’s executive deputy, stand at the Route 66 Eagle, Globe and Anchor pavement marking at Marine Corps Logistics Base Barstow, Calif., on Oct. 22, 2021. Officials dedicated a new monument near the marker Nov. 9. (Jack J. Adamyk/U.S. Marine Corps)

It was used to decorate the base’s Marine Corps birthday cake, and it was memorialized in a towering sculpture of gleaming brass and steel.

The symbol was “approved enthusiastically” and trademarked by Headquarters Marine Corps after first being unanimously approved by the California Historic Route 66 Association, Thompson said. Base documents say the logo can only be used there.

The Route 66 segment is eligible for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places and is just one of the base’s 227 archaeological resources, official documents say.

“If there’s one thing Marines prize, it’s our history,” Col. Craig C. Clemans, the post’s previous commanding officer, said in an April statement recognizing Thompson and others for their management of cultural resources, including the historic roadway and several Native American rock carvings.

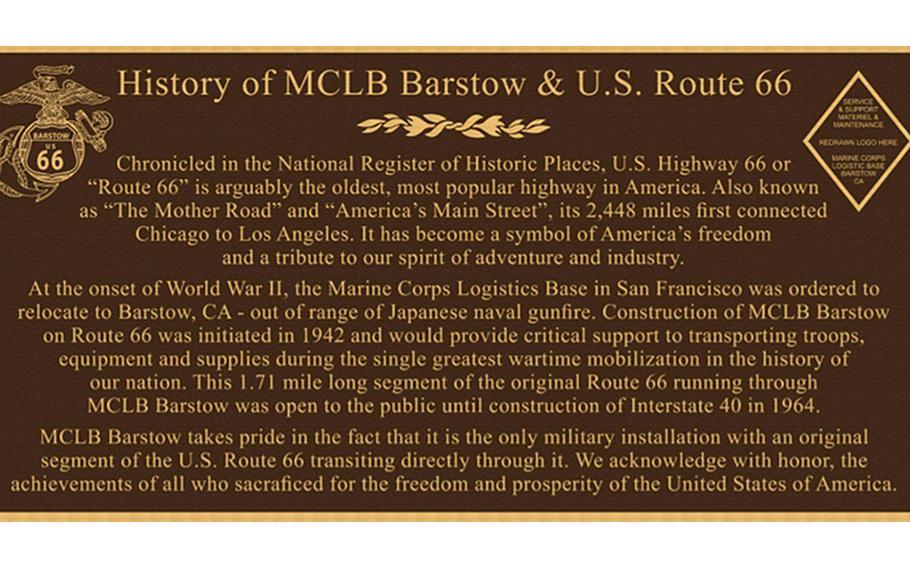

An illustration of a 4-foot-long bronze plaque that is displayed outside the front gate of Marine Corps Logistics Base Barstow, Calif. It recognizes the ties between the base and the historic U.S. Highway 66. The route was an artery for the U.S. military mobilization during World War II. (Marine Corps Logistics Base Barstow)

Also called the “Mother Road,” Route 66 was the first all-weather highway from Chicago to Los Angeles, wending its way for some 2,400 miles.

While it may evoke thoughts of scenic road trips and kitschy roadside attractions from America’s postwar economic boom, it also played a major part in U.S. efforts during World War II.

During the unprecedented U.S. mobilization for the war, it served as an artery for the movement of troops, gear and supplies between bases. It also carried job-seekers west for work in defense plants, the National Park Service has said.

To put its supply depot for the Pacific theater out of range of Japanese naval gunfire, the Marines moved it from San Francisco to a spot the Navy gave it along the desert highway northeast of LA in December 1942.

Bursting at the seams after the war, the base was expanded with the purchase of 2,000 acres from the Army in 1946. The 5,500-acre installation is now home to the military’s largest rail facility, supporting troop rotations at the nearby National Training Center at Fort Irwin and other West Coast bases.

An undated photo of a new marquee outside the front gate of Marine Corps Logistics Base Barstow that recognizes the ties between the base in California’s Inland Empire and the historic U.S. Highway 66. The Barstow base is the only military installation with a segment of Route 66 running directly through it, base officials said. (Marine Corps Logistics Base Barstow)

The strip of asphalt there isn’t the only thing connecting the Corps and the historic highway, though. Both are also linked through the popular song “(Get Your Kicks on) Route 66,” which musician Bobby Troup wrote shortly after he left the Marines as a captain in 1946 while moving his family to Hollywood.

These days, drivers heading west need permission to pass through the base’s front or back gates on the “highway that is the best.”

But Thompson said new kiosks at special marquees outside both entrances provide historical information to any visitor who wants to stop.

And just before Veterans Day last month, officials held a ceremony to dedicate the shimmering 6-foot-tall metal sculpture of the modified Eagle, Globe and Anchor on a pedestal in the middle of the base.

“The biggest drawback is that the only way you can see the statue is if you have permission to access the base,” Thompson said. “You won’t see it anywhere else.”