The 61-foot crab boat Genesis is grounded on a sandbar off Leadbetter Point at the entrance to Willapa Bay, Wash, Jan. 25, 2013. The Coast Guard rescued all four crewmembers and a dog. (U.S. Coast Guard)

BAY CENTER, Wash., (Tribune News Service) — To reach the ocean crabbing grounds from this Southwest Washington community, Mike Green must navigate his boat through the seas that churn across the mouth of Willapa Bay. There are no jetties to sweep out the piling sediments, or buoys to mark a channel through the breakers.

“You look for gaps,” Green said. “There’s about a half-mile of water you got to dodge through.”

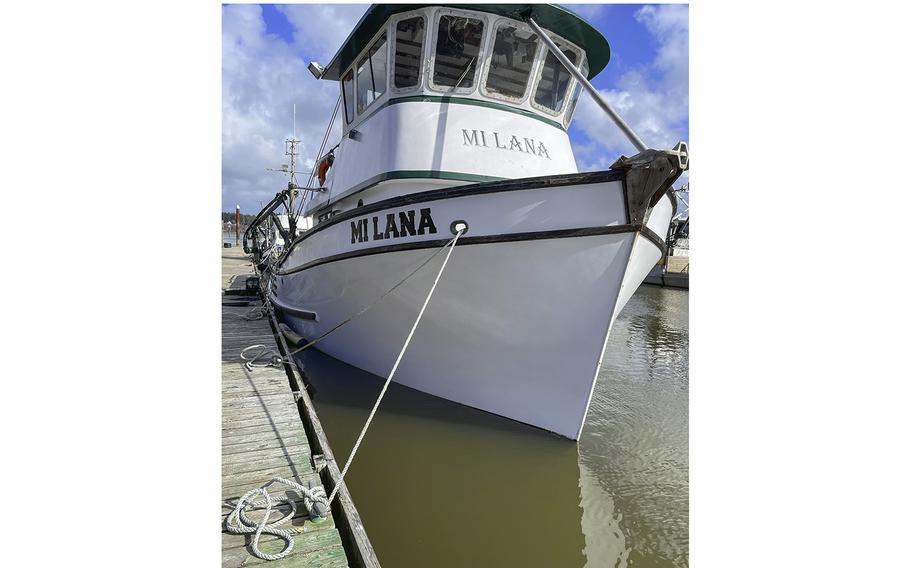

Through the years, the 69-year-old Green has had some close calls. Waves once shattered the wheelhouse windows of his boat, the 52-foot Mi Lana. This winter, he suffered a far more grievous loss.

His grandson, Bryson Fitch, 24, went missing Feb. 5 after the vessel he was working on — the Ethel May — capsized in an attempt to cross the mouth of the bay.

Fitch’s fate was a brutal reminder of the perils of the Willapa Bay bar, and of the risks of the Pacific Northwest Dungeness crab fishery, which since 2000 has claimed 49 lives and ranks as one of the deadliest fisheries in the country.

Fitch’s loss was a sledgehammer blow to his family and a community of some 250 people with an economy long tied to shellfish.

Mike Green, seen here digging out a mole hole on his family property in Bay Center, has spent most of his life traversing the Willapa Bay bar to find crab in the ocean. Up until last year, he employed his grandson Bryson Fitch as a crew member aboard his 52-boat, the Mi Lana. This year, Fitch went out on a different boat that capsized Feb. 5, 2023, and he was lost at sea. (Hal Bernton/The Seattle Times/TNS)

Green had a big role in raising his grandson, whose own father was largely absent from his childhood. And Green taught him about the sea.

“Wherever my dad was, that’s where he (Fitch) wanted to be,” said Becky Hancock, Green’s daughter. “My dad was his role model. His mentor growing up.”

Green took Fitch, while still in grade school, across the bar to get a sense of the winter Dungeness harvest. Later, he hired Fitch as crew aboard the Mi Lana. Prior to the start of this season, Fitch decided to continue crabbing and join his cousin Doug Will, aboard the Ethel May.

The vast majority of commercial crabbers who work off Washington’s coast want nothing to do with Willapa Bay. They are based in Ilwaco, Chinook, Westport or other ports with easier access to the sea.

Will’s 46-foot vessel was a 76-year-old boat that he had just acquired last year, according to Green and other family members. The Ethel May got knocked over by waves as the crew attempted to return to Bay Center to pick up a load of pots before the opening of the Dungeness harvest on March 6.

Will and a second crewman made it into a life raft and were rescued by a Coast Guard helicopter team.

Hundreds of volunteers searched the expansive beaches in hopes of finding Fitch’s body. His family launched a “Bring Bryson Home” Facebook page where people could post about what they had found, and they set up a GoFundMe page to raise money for his wife, McKenzie Salas, and their three young children.

While pieces of the boat, which broke up in the surf, have been found along the beaches, Fitch remains lost at sea.

“He loved his kids. He loved to ride motorcycles. He loved crab fishing,” said Bryan Damon, a 32-year-old Bay Center crabber. “It’s part of the family legacy. Most of us out here, it’s kind of all of our legacy.”

Shifting shoals

Mike Green learned about crossing the bar of Willapa Bay from his father, Merrill Green, an Idaho farmer who moved in the early 1950s to Bay Center, where the family’s first house was built out of old wooden boxes from the oyster industry.

Merrill Green ran a trucking business and acquired a 28-foot plywood boat, which he extended by 6 feet, and used to venture to the ocean to troll for salmon and catch crab. Mike and his older brother Marvin sometimes served as the crew.

Back then, the Army Corps of Engineers dredged the bay entrance, enabling more maritime traffic to cross the bar, including deep-draft vessels that hauled away logs cut from coastal forests.

Constantly shifting shoals made the passage increasingly difficult, and the last deep-draft vessel crossed in 1976. Two years later, the Army Corps stopped dredging.

A 2021 Coast Guard report about the bar noted the “sea can break into dangerous surf at any time in this area,” and cautioned that mariners should only attempt the crossing “if you are intimately familiar with the entrance.”

There had once been as many as five navigation buoys marking the way through. The 2021 report recommended that the last be pulled. They frequently broke loose and Coast Guard officials concluded that a buoy tender could no longer safely navigate the bar to service them.

“The primary reason is the shifting and shoaling there. So, we can’t get the vessel in and out (of) Willapa,” said Cmdr. Brendan Harris, waterways branch chief for Coast Guard District 13, who approved the recommendation to remove the last two buoys.

‘Fish-or-go-hungry’ mentality

As the bar crossing became more treacherous, the size of the oceangoing crab fleet working out of Willapa Bay ports dwindled.

Most of the crabbers who have remained in Bay Center, which spreads out along a narrow peninsula, have smaller boats and opt to largely crab within Willapa Bay, where catches are typically smaller but there is no need to make a bar crossing.

The community of Bay Center spreads along a narrow peninsula that juts into Willapa Bay. From this beach, you can peer out toward the bay mouth, where a notorious bar can make it a difficult passage to the sea. (Hal Bernton/The Seattle Times/TNS)

At the start of this season, only Green and his nephew, Will, skippered Bay Center boats that crossed the bar to crab in the ocean.

Green carefully monitors conditions, and strives to only make the crossing when the ocean swells are less than 12 feet. And if he needs to come to port but the bar looks like too great a risk, he jogs north to cross Grays Harbor bar, a dredged and well-marked passage, to moor at Westport.

“Most guys think we’re crazy going in and out of here,” Green said.

With salmon harvests far lower than in decades past, the Dungeness crab that they pursue has emerged as Washington state’s most important commercial harvest.

Last season, 199 commercial crabbers received a record average price of $5.78 per pound for their Dungeness in a harvest of 15.2 million crab, worth $88.23 million, according to the state Department of Fish and Wildlife. That worked out to an average gross of $433,367 per boat before expenses, and additional crab were caught by tribal fishermen who under a 1994 court decision are entitled to half the harvest from their usual and accustomed areas.

This is a high-pressure fishery.

During the first crucial weeks of the winter harvest, much of Washington’s fleet is concentrated in a 38-mile stretch of water north of the Columbia River.

Once the season opens, catch rates quickly plummet, so fishers strive to keep working even as the ocean turns rough.

“It’s fish-or-go-hungry insanity. That area is so compressed that the crab are sucked up pretty fast,” said Dale Beasley, a retired crabber and president of the Columbia River Crab Fishermen’s Association.

Ebb at the bar

The start date of the ocean Dungeness harvest varies from year to year and is closely tied to the amount of meat inside the crab shells. Last season, monitoring by state biologists found the crab filled out early, enabling a Dec. 1 start for the harvest.

This winter, the crab developed more slowly, and the opening of the ocean harvest zone off Bay Center was pushed back to Feb. 6.

The 52-foot Mi Lana is one of the few boats based inside of Willapa Bay that ventures across the bay-mouth bar – which lacks navigation aids, jetties and dredging – to crab in the ocean. The boat is skippered by Mike Green, who is 69. After the loss this year of his grandson Bryson Fitch and the capsizing of another vessel, Green is uncertain whether he will continue to crab next year. (Hal Bernton/The Seattle Times/TNS)

Before the harvest’s start, Green’s Mi Lana and Will’s Ethel May left Willapa Bay, and both crossed the bar to lay down their pots along the sea bottom.

They had 73 hours allotted by state regulators to complete this task. Then, they were required to return to a port to have their holds checked to make sure no early crabbing had occurred.

Green set two loads of pots, and on the morning of Feb. 5 — on a rising tide — was able to make it back across the bar to Bay Center.

Sunday evening, a storm system intensified, churning the Pacific.

In coastal waters some three miles beyond the Willapa Bay mouth, crabber Ben Downs, skipper of the Rising Sun, ran into trouble. He was trying to make his way back to Westport when, at about 7:30 p.m., he encountered 16-foot seas that hit at 8-second intervals.

“We took a couple of big ones. I had standing water in my wheelhouse,” Downs said. “It was bad.”

About the same time, Will attempted to return to Bay Center in the Ethel May. The water ebbed and waves built along the bar. Calls to 911 streamed into the Pacific County Sheriff’s Office from family and friends alerting emergency officials that the boat had capsized, according to a dispatcher’s call log. There also appeared to be multiple calls from a crew member aboard the boat, although the dispatcher noted, “I do not believe he can hear me, sounds very muffled and sounds like water.”

As the Ethel May was knocked over by the waves, an emergency radio beacon began broadcasting to the Coast Guard. The boat was equipped with a canopied life raft that floated free and inflated.

Will and another crewman made it into the raft and were airlifted to safety by a helicopter crew from the Coast Guard, which released a video of the rescue.

Green and other family members are uncertain what happened to Fitch. They think he got to the raft but somehow was unable to hold on, Green said.

Coast Guard officials, citing an open investigation, have declined to release any additional information about the incident gleaned from interviews with the two survivors or even their names.

Oysters and fishing are the two mainstays of the economy of Bay Center in southwest Washington. In this port area, crab boats that work the winter harvest unload their catch as they come back from harvest areas. (Hal Bernton/The Seattle Times/TNS)

Will, the surviving skipper, told a Seattle Times reporter: “I got nothing to say.”

Weighing the next season

After the loss of the Ethel May, Green spent 10 days shoreside during the peak of the Dungeness crabbing season.

He joined in some of the beach searches, but hoped he would not be the one to find his grandson. He spent much of the time at his homestead with other family members who gathered there.

Green had three daughters, one of whom had died in an automobile accident. The births of his grandson and his sister, Kelsea Broddy, had brought the sparkle back to his eyes, according to Hancock, Green’s daughter, who recently moved in with her father to help him through this tough time.

“He won’t talk about Bryson because it’s probably just too hard now,” Hancock said.

Yet at sea, there still was work to be done.

Green was now the last Bay Center crabber fishing in the ocean. Hundreds of his own pots — as well as those put down by his nephew — were baited, set and trapping Dungeness.

In mid-February, he headed back out across the bar to retrieve them.

This task was greatly complicated by another big storm that stirred up 30-foot waves and powerful currents that scattered the pots — each attached to a floating buoy — across a wide area.

In a corner of a Bay Center cemetery, a statue represents fishers lost at sea who had ties to this small southwest Washington community of some 250 people. There are 21 names dating back to 1905. (Hal Bernton/The Seattle Times/TNS)

Some were clear into the surf, such shallow water that Green could not retrieve them. The locations of others remained a mystery.

Markets for the crab pulled from those pots were another source of frustration.

Prices paid to crabbers this year started around $2 a pound, less than half of last year’s average price, before edging up to $2.75 a pound by early March. By then, catch rates for Green had plummeted.

“I’m just trading dollars. For the price of bait and fuel, you can’t make it,” Green said.

He is unsure about the future. He wrestles with the grief over the loss of his grandson and the ongoing demands of the harvest season.

If he can find someone to buy his boat and permit, Green said, this might be his last season.

Then again, maybe he will hang on another year, and yet again cross the Willapa Bay bar in search of Dungeness.

(c)2023 The Seattle Times

Visit The Seattle Times at www.seattletimes.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.