Army Brig. Gen. Jin Pak, commander of the 19th Expeditionary Sustainment Command, shows some of the awards in his office in Daegu, South Korea, Oct. 18, 2024. (Luis Garcia/Stars and Stripes)

DAEGU, South Korea — Jin Pak was 6 years old when he left South Korea alone, flying halfway around the world to reunite with parents he barely knew. They had immigrated to the United States soon after his birth, leaving his grandparents to raise him until they were ready for him to join them.

“Whenever I saw a plane, I’d say that I’m going on that plane and go to America,” he said in a recent interview at Camp Walker in Daegu.

Forty-six years later, the Army brigadier general is back in South Korea, leading the 19th Expeditionary Sustainment Command in Daegu.

A naturalized U.S. citizen who was commissioned at West Point, Pak first returned to his native country as a soldier in 2012 to command the 25th Transportation Battalion for three years. In June, he took over the sustainment command, which handles the Army’s logistical operations on the peninsula. He is responsible for approximately 5,600 soldiers and Defense Department employees.

Pak’s journey from a child immigrant to a one-star general in the U.S. Army is both typical and unique.

“I’m very proud of it because it’s an example of how … America is also a place of opportunity,” he said. “I don’t know of many countries where an immigrant, not of that country’s ethnicity, could join their military and rise to the rank of general officer.”

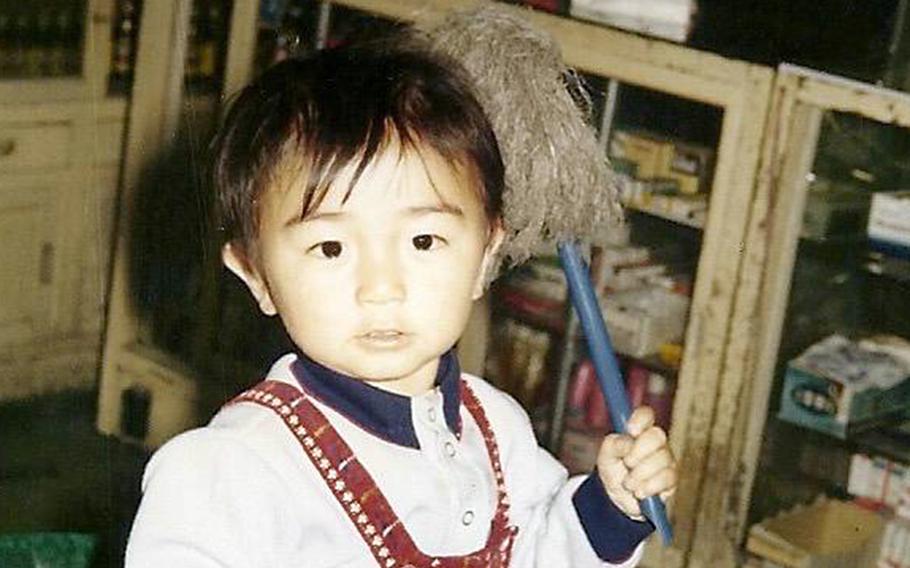

U.S. Army Brig. Gen. Jin Pak as a child living in South Korea. (Jin Pak)

Pak said his parents left South Korea for reasons that remain unclear to him.

“I’ve asked that question and they’re not very specific about it,” he said. “But I get the sense that they wanted to try something new. I know they were both very ambitious.”

Korean immigrants to the U.S. often left their children behind temporarily, particularly in the decades following the 1950-53 Korean War, said Dae Young Kim, a sociology professor at George Mason University in Virginia.

Many immigrants had limited funds and worked multiple jobs to make a living, Kim said in a video interview last month. Faced with child care costs and work demands, parents found alternative ways to raise their children.

“One option is to be able to bring your own parents to the U.S., and that’s something that some immigrants, including Korean immigrants, have done,” Kim said. “The other option is to send the child [away] so that the children can be taken care of until they reach a certain age and can be somewhat independent.”

Pak arrived in the U.S. in 1978 and moved into a one-bedroom apartment in Elmhurst, Queens, with his parents and younger brother, who was born that same year. He recalled feeling “very out of place” and being bullied for not knowing English.

“My third-grade teacher reported me to my parents because she said I was causing a lot of fights,” he said. “But I was in fights; I wasn’t causing the fights. It was that kind of childhood for a while.”

Pak became a U.S. citizen in 1981. His naturalization certificate is the only official document with his birth date due to inadequate record-keeping in South Korea at the time, he said.

“I don’t have a birth certificate,” he said. “I only know I was born in 1972 because of my citizenship paperwork.”

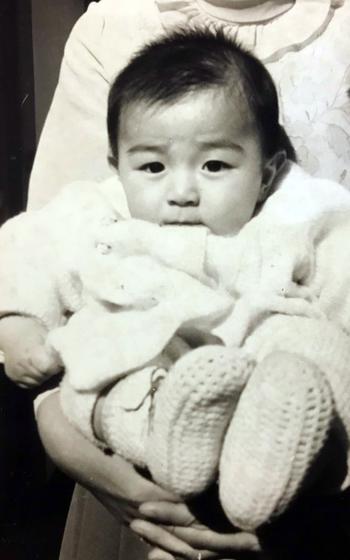

U.S. Army Brig. Gen. Jin Pak as an infant living in South Korea. (Jin Pak)

Pak graduated from West Point in 1994. His father, a stoic man who “doesn’t show a lot of emotion,” was proud of his son attending the military academy, he said.

“He actually sent me hand-written letters asking me how I was doing, stuff that I would never have imagined in a million years he would do,” Pak said.

One of Pak’s fondest memories is of his father mailing him candy bars hidden inside a flashlight, a trick soon discovered by the school.

“I’ll never forget that,” he said, smiling.

Pak’s father attended his graduation, but that summer, he suffered a heart attack and fell into a coma. He died less than two years later.

“He saw me graduate, but he never saw anything else, like marriage and grandkids,” said Pak, now a father of two adult children. “I know he would be very proud and happy about it. I do regret that he hasn’t seen my career unfold because I knew he appreciated military service.”