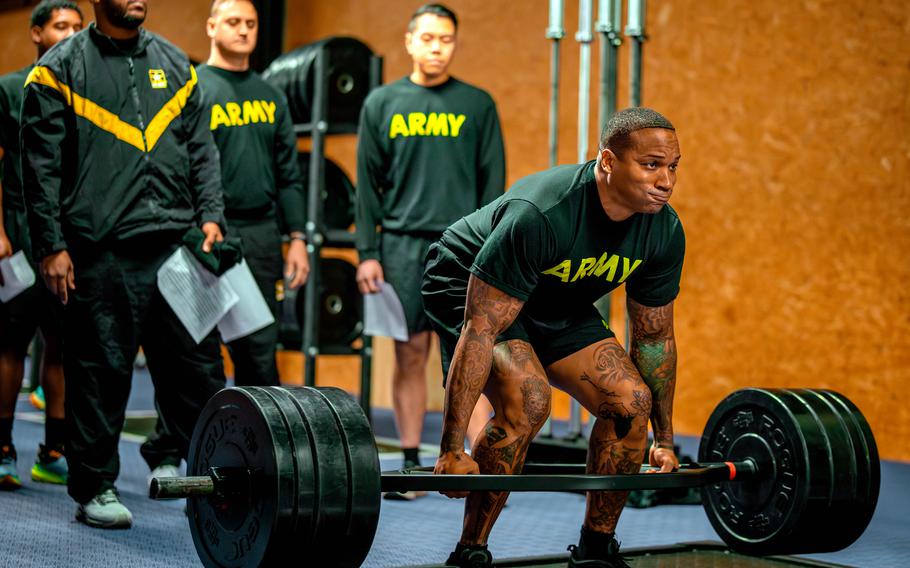

Soldiers do deadlifts during an Army Combat Fitness Test on Dec. 12, 2024, in Sembach, Germany. The Army can safely raise minimum fitness standards for close combat jobs, but setting the bar too high would test the service's acceptance of lower pass rates, according to a new study. (Yesenia Cadavid/U.S. Army)

The Army can raise the bar on minimum fitness standards for close-combat jobs and also must establish clear consequences for soldiers who fall short, according to the recommendations from a new study on the implications of demanding more from front-line troops.

The Rand Corp. study, released Friday, found that higher standards for select military specialties, such as infantry and combat engineers, can be implemented as a means to ensure better fitness for those in more physically demanding positions.

But the Army’s ability to achieve desired fitness test pass rates for those jobs hinges on how high it sets a new minimum standard, the service-commissioned report said.

Between May and August, the Army tested higher potential standards among a sample of more than 44,000 soldiers in close-combat jobs. Rand’s analysis of the results showcased potential trade-offs associated with alternative approaches.

For example, raising the overall Army Combat Fitness Test minimum from its current 360-point total up to 450 points and a minimum deadlift requirement of 150 pounds — levels the Army wanted for the trial — may be too high if the aim is to achieve a 95% overall pass rate and a 90% pass rate for select subgroups, Rand said.

Under that standard, active-duty soldiers in the regular Army scored a 91.4% pass rate, while several subgroups had rates below 90%.

Pass rates for soldiers in the National Guard and reserves were “significantly lower” under this standard, coming in at under 75%, Rand said.

Soldiers participate in the Army Combat Fitness Test at the 7th Army Training Command's Grafenwoehr Training Area, Germany, Oct. 8, 2024. The Army can safely raise minimum fitness standards for close combat jobs, but there are consequences in setting the bar too high, according to a Rand Corp. study released Dec. 20. (Christian Carrillo/U.S. Army)

The study was prompted by a bill Congress passed last year requiring the Army to elevate fitness standards for infantry, combat engineering, armor and cavalry, artillery forward observers, engineer and artillery officers and all Special Forces soldiers.

The congressional mandate was aimed at addressing concerns related to the fitness test’s shift from being age- and gender-neutral, as it was originally proposed several years ago, to one that now has tailored standards.

To address those concerns, Congress called for higher minimum fitness standards for soldiers in front-line jobs. However, the legislation didn’t specify how far beyond the current minimum test score of 360 points the new standard should go.

Rand noted that younger, female soldiers had lower pass rates when the test’s deadlift standard was increased from a minimum of 120 pounds to 150 pounds.

The Army Combat Fitness Test is made up of six events: deadlift, standing power throw, hand release pushup, sprint-drag-carry, planks and the 2-mile run.

An overall minimum standard of 420 points would be enough to ensure the general fitness of soldiers for combat jobs, while setting the level at 450 points would require enhanced fitness, the report said.

As the Army sorts out how to implement higher standards for combat jobs and how high it should go, it should set up “glide paths” that allow soldiers sufficient time to train and improve, Rand said.

It also must make sure that sufficient training resources are delivered down to lower unit levels, such as squads and companies.

Meanwhile, the Army will need to establish “a clear and consistent message” that “includes transparent policies for failure to meet close combat ACFT standards,” Rand said.