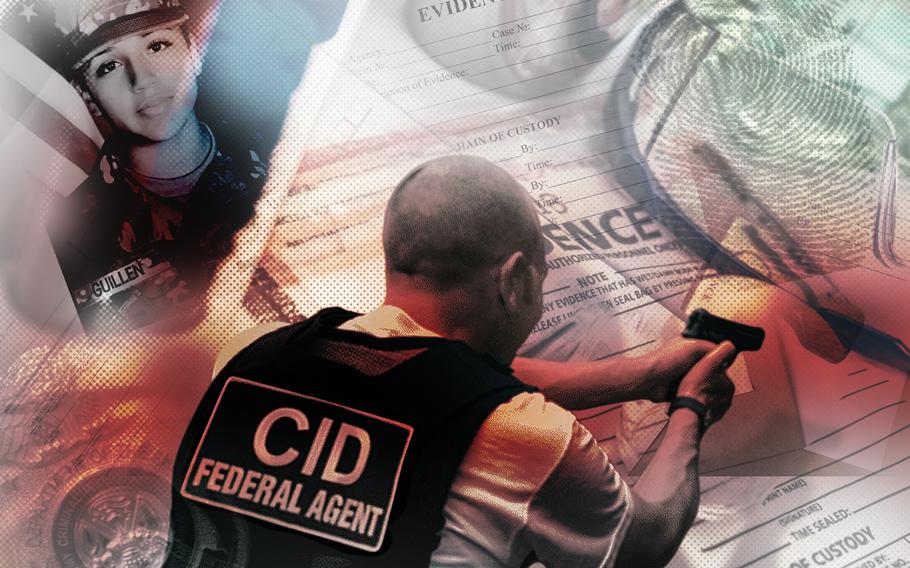

The Army Criminal Investigation Division has hired more than 355 civilian agents in the three years since an independent report called for the agency to improve professionalism, trust and its authority to investigate Army-centric crime that occurs outside the gates of a military installation. (Illustration by Noga Ami-rav/Stars and Stripes)

The Army Criminal Investigation Division has hired more than 355 civilian agents in the three years since an independent report called for the agency to improve professionalism, trust and its authority to investigate Army-centric crime that occurs outside the gates of a military installation.

Gregory Ford, who became CID’s first civilian director in September 2021, said the agency is still pushing to hire another roughly 500 civilian investigators in the next few years with a goal of its investigative arm being 60% civilian. It is now comprised of 60% active-duty soldiers, he said.

“It’s a challenging hiring environment,” he said during a March interview at CID’s headquarters in Quantico, Va. Law enforcement agencies across the country have struggled to fill vacancies and many are experiencing personnel shortages in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, according to the Justice Department. However, Ford said there continues to be a steady stream of soldiers who want to transition to be civilian agents — making up about half of those 355 already hired.

The Naval Criminal Investigative Service and Air Force Office of Special Investigations — CID’s officemates at the Russell-Knox Building in Quantico — already operate with staffs that are made up mostly of civilian agents.

The push for the transition came from a 2020 report following the death of Spc. Vanessa Guillen at Fort Cavazos, the central Texas base formerly known as Fort Hood.

The soldier was killed on base by another soldier and then moved off the post, where she was found buried more than two months later.

As agents searched for the soldier, her family pleaded for more to be done and alleged Guillen faced sexual assault and harassment at the base, the latter of which was later confirmed by the Army. Guillen’s sisters protested outside of the base multiple times with supporters and gained national attention.

Then Army Secretary Ryan McCarthy put together an independent review commission, which made dozens of recommendations to improve the Army’s sexual misconduct prevention and reporting program, its public affairs offices, its approach to building trust between enlisted soldiers and leaders and its CID office structure and operations.

The report described the workforce in the base’s CID office as “unstable, under-experienced, over-assigned and under-resourced.” Those issues led to “inefficiencies that had an adverse impact on investigations, especially complex cases involving sex crimes and soldier deaths.”

The committee determined these inefficiencies stemmed from staffing protocols and other policies and procedures that impacted the division. It recommended — and the Army mandated — major reforms intended to improve these problems.

Improving partnerships

“It’s a daily effort for us,” said Ford, who previously worked at NCIS and the FBI. “We’re continuing every day working a very challenging mission, while in the midst of that, transforming the organization. It does not come without challenges by any means.”

Civilian agents are not subject to the same deployment and reassignment moves as soldiers, which means they can build more time and experience in one location.

Civilian agents also have more authority and jurisdiction off Army property, Ford said. Having more civilians allows for more joint investigations and helps the agency investigate more crimes that have an Army affiliation or an impact on the service beyond just the location where it occurred, which the Fort Hood report cited.

Investigations worked jointly with local or federal law enforcement agencies increased from 600 in fiscal 2021 to more than 1,500 in fiscal 2023, which ended in September, according to CID.

Agents now partner with the Justice Department’s Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, the Drug Enforcement Administration’s Strikeforce and a central Texas fentanyl task force. There are also CID agents embedded now with local police departments near Army bases.

In October, the fentanyl task force’s work led to the arrest of four people whose trafficking involvement led to the overdose death of an Army spouse at Fort Cavazos.

However, more civilian agents and more joint investigations have also set up a situation where some soldier agents feel threatened or undervalued because they have less authority. Ford said he’s combating this perception with the term “one CID.”

This is visually reinforced in CID’s Quantico headquarters with photos in the lobby and throughout the halls that depict soldiers and civilians working together to solve crimes. New signs adorn conference rooms and waiting areas featuring the agency’s new logo that reflects its name change and that it is civilian led. When helmed by a general officer, it was Criminal Investigation Command.

“We’re made up of 3,000 plus individuals all contributing something in the mission. At the end of the day, we are one CID with one mission. We have to work together,” Ford said.

Bolstering prevention

Another dozen positions were added to the Army’s Criminal Investigation Laboratory in Forest Park, Ga., which processes evidence for the entire Defense Department, according to CID. In the past two years, the lab worked on more than 4,000 cases.

So far, the new hires have bulked up the staff and helped improve turnaround time for sexual assault cases by 40% — moving from an average of 64 days in fiscal 2022 to 36 days the following year, according to CID.

In the restructure, CID’s director now reports through a civilian leadership structure to Army Undersecretary Gabe Camarillo, who described the ongoing progress in the agency as “commendable.”

“Coupled with the establishment of the operational Office of Special Trial Counsel, CID transformation continues to bolster the Army’s efforts to prevent and address sexual assault crimes,” he said, referencing the new legal process for some crimes that has similarly been established outside of the uniformed chain of command.

But sexual misconduct has remained a serious issue in the military despite concerted efforts and spending to combat the crisis.

The most recent Defense Department report on sexual assault among troops – released about one year ago – showed numbers increased slightly in 2022 in all service branches except the Army. That followed a massive 26% rise for the service in 2021.

During Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin’s first year on the job, he ordered an independent committee — similar to the one that investigated Fort Cavazos — review sexual assault and harassment. It came back with more than 80 recommendations, including creating the independent prosecution office.

Since December, special prosecutors are now responsible for deciding whether a soldier will face a court-martial for certain felony crimes, including murder, sexual assault and domestic violence. The decision had been made by commanders. While Congress had been pushing for this move for more than a decade, the events of 2020 forced the effort forward.

Under the advisement of the new Office of Special Trial Counsel, two sexual misconduct cases had charges dropped because of evidence problems — one at Fort Cavazos involving a colonel and another involving five soldiers at Fort Johnson, La.

Ford said, in each instance, the agency learns in real time how to make improvements for future investigations, though he did not elaborate on any specific lessons in these two cases.

“We’ve got a continuous improvement mentality,” he said.