Employees make signs using the “Fort Barfoot” name to replace existing “Fort Pickett” signs on March 6, 2023, at Fort Pickett, Va. (Mike Vrabel/U.S. National Buard)

BLACKSTONE, Va. — Pickett.

For as long as anyone here can remember, that is how the sprawling military base neighboring this tidy little town in southern Virginia has been known.

Named for Confederate General George Pickett, it was first established as Camp Pickett when the Army built it as a combat training ground soon after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. Then, in 1974, the then nearly 45,000-acre facility was renamed Fort Pickett.

But the Pickett era ends Friday when the name will come down as part of a sweeping congressional order to the Defense Department to remove Confederate names from its installations and assets. Pickett, which has been operated by the Virginia National Guard since 1997, will be renamed Fort Barfoot after Col. Van T. Barfoot, a World War II Medal of Honor recipient who lived in nearby Amelia.

While this part of Virginia is steeped in Confederate history and a statue of a Confederate soldier stands in front of the county courthouse a few miles away, the decision to rename the base wasn’t met with a flurry of protests or upset residents demanding the old name be kept. If anything, the decision has been greeted by many locals with little more than a shrug.

Some here say they’ll keep calling it Pickett. Others are fine with moving on. Many say they simply haven’t given it much thought at all.

“Truly I don’t care what they call it as long as they keep it open,” said Gus Mitchell, 63, who owns Mitchell’s restaurant, a popular stop for locals in the diverse town of about 3,500 residents that is in the midst of a small growth spurt. “Do what you want to do. Keep training out there, and everything will be lovely.”

In addition to its combat training mission, the fort is also home to Virginia National Guard’s 183rd Regiment, the Virginia Department of Military Affairs and the U.S. State Departments Foreign Affairs Security Training Center. All told, the base employs about 1,000 civilian and military personnel.

Mitchell, who has lived here since he was 6, said the fort “has always been the backbone of the town” and has kept its economy afloat. He said he’ll continue to call it Pickett because that’s what he’s used to.

Why the fort was first named for Pickett, a U.S. Military Academy graduate from Richmond who fought for the Confederacy and helped lead an infamous, ill-fated charge at the Battle of Gettysburg on July 3, 1863, is still something of a mystery in these parts.

Billy Coleburn, owner of the local newspaper and former mayor of Blackstone, walks down Main Street in September 2021. (Julia Rendleman, for The Washington Post)

“We country bumpkins down here didn’t come up with the name,” Billy Coleburn, the owner of the local newspaper, the Courier Record, and a former mayor of the town, said in an interview at his office here last week. “The War Department picked the land and the name and the day of the dedication.”

The Army dedicated Camp Pickett on July 3, 1942, 79 years to the day after Pickett’s costly loss at Gettysburg. A number of his descendants planned to be there for the ceremony, according to coverage in the local paper.

In the first half of the 20th century, naming military installations in the South for Confederate leaders was part of the Lost Cause effort, said Ty Seidule, a U.S. Military Academy historian and retired U.S. Army brigadier general, referencing efforts by leading Southerners to cast the Confederacy as noble and principled rather than a rebellion from the North in an attempt to hold on to slavery. In addition to Fort Pickett, two other Virginia military bases named for Confederates, Fort Lee and Fort A.P. Hill, were ordered by the military to change their names this year.

Seidule, a Virginia native who served as vice chair on the federal Naming Commission tasked with identifying Confederate names in military locations and recommending new ones, said Pickett was thoroughly undeserving of the honor of having a base named for him.

“Pickett was a war criminal who summarily executed 23 U.S. Army soldiers in 1864 and then skedaddled to Canada because he was fearful of being hanged,” Seidule said.

At Pickett, it isn’t just the name of the fort that’s changing. Four buildings, 19 roads and five bridges on the base — which continues to serve as a combat training facility — were also identified by the commission to be redesignated. Those include roads named for Confederate soldiers and officers including generals J. E. B Stuart and Stonewall Jackson.

Established by Congress in 2021 and prompted in part by the calls for racial justice following George Floyd’s murder, the Naming Commission was tasked with removing vestiges of the Confederacy from the military and recommending names that reflect the nation’s broad diversity.

In addition to Pickett, the naming commission identified eight other bases for name changes including Fort Bragg in North Carolina, Fort Benning in Georgia and Fort Hood in Texas. It also identified Navy ships, buildings, street names and memorials at military locations across the country to be changed.

In January the Defense Department ordered that all of the approximately 1,100 changes be implemented by the end of this year. The commission estimated last year that the cost for implementing the changes will be more than $62 million.

Seidule said renaming the Fort Pickett for Barfoot would make anyone who served there proud.

“If you read his Medal of Honor citation it will buckle your knees,” Seidule said.

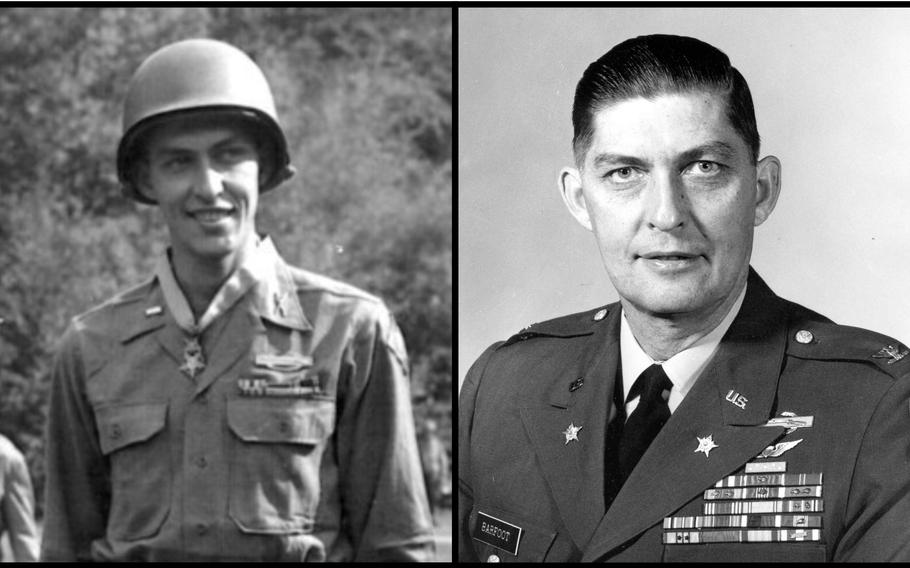

Van T. Barfoot, after receiving his Medal of Honor during World War II (left) and as a colonel (right). The Virginia National Guard’s Fort Pickett will officially be redesignated Fort Barfoot in honor of Barfoot, who has extensive Virginia ties. The ceremony is scheduled for March 24, 2023, in the Fort Pickett area near Blackstone, Va. (Cotton Puryear/Virginia National Guard)

Barfoot was awarded the medal for his actions in May of 1944 with the 45th Infantry Division in Italy confronting German soldiers and tanks. In a single battle he neutralized two machine gun nests, captured 17 enemy soldiers, disabled a tank with a bazooka and led his fellow soldiers who were wounded to safety.

He remained in the military for 34 years and served tours in Korea and Vietnam, according to a Virginia National Guard press release. Barfoot, whose grandmother was a member of the Choctaw Nation, will also have his Native American heritage honored at Friday’s renaming ceremony with members of the Choctaw Nation and Virginia-based tribes participating in ceremonial songs and dance.

For Maj. Gen. Timothy P. Williams, the Adjutant General of Virginia whose command includes Fort Pickett, the choice of the new name made it an easy one for the military to accept.

“I’m super excited about it,” said Williams, a World War II history buff who met Barfoot once in 2000. “We had 10 names considered by the commission and they were all phenomenal choices. But the opportunity to name the installation after [Barfoot] resonates with soldiers. And because he was in the community it’s hard not to embrace that.”

Sheila Matthew, the manager of Blackstone Antiques and Crafts Mall on Main Street for the past 17 years, said she didn’t really understand why the name of the base had to change and she’s a little sad that it is happening. But, she said, she’s pleased it is being renamed for someone with Native American heritage.

“I’ve always said we took the country away from the Indians so it’s good thing to do a thing like this,” said Matthew, who is white. “We’re glad about that.”

William and Gina Stith, an African American couple who live in nearby Crewe, Va., said they supported changing the name of the fort. William Stith, a Marine Corps veteran, said it “sent the right message because it shouldn’t be named for a Confederate.”

“It’s a good move for the community,” he said.

Coleburn, the newspaper owner and former mayor, thinks the name change at the base has gone smoothly because the Army and the Virginia National Guard did a thorough job of informing the town and county about the process and engaging residents in every step, including soliciting suggestions for new names for the fort. Settling on Barfoot also helped, he said.

“Barfoot is a true warrior and there’s no question of his credentials, so that has minimized some of the potential blowback,” he said.

That the changeover has gone so smoothly is a testament to the process and the American people, Seidule said.

“It just shows that Americans can work on a bipartisan or even nonpartisan basis to do the right thing,” he said. “And I think that’s exactly what happened here.”

The entrance to Fort Pickett in Blackstone, Va. The fort will be renamed Fort Barfoot on March 24, 2023. (Joe Heim/The Washington Post)