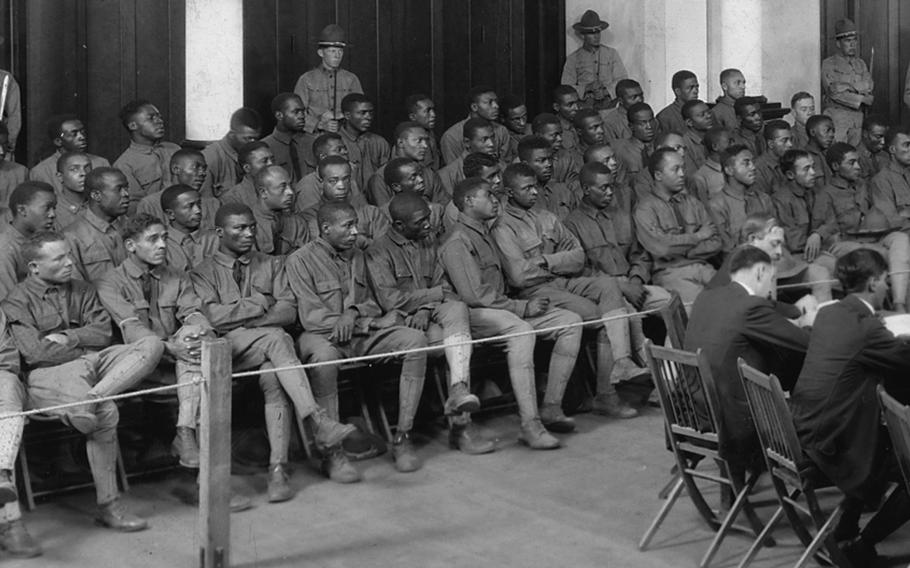

Defendants on trial during the first court-martial at Fort Sam Houston, Texas, in November 1917. Following the Houston Riots of 1917, 63 soldiers were tried during one court-martial, the largest in U.S. military history. Two more trials followed and 19 men were hanged for mutiny. (National Archives and Records Administration)

SAN ANTONIO, Texas — Jason Holt’s family has preserved a letter that his uncle, Army Pfc. Thomas Hawkins, wrote nearly 105 years ago.

The letter and the events it describes led Holt on a decades long journey to clear the legacy of his uncle, who was one of 19 Black soldiers executed in 1917 and 1918 after courts-martial found them guilty of charges stemming from a race riot in Houston that left 19 people dead.

Hawkins professed his innocence in his letter. On Tuesday, Holt said he felt one step closer to clearing his uncle’s name. The Department of Veterans Affairs unveiled a sign at Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery in San Antonio to acknowledge the race riots that led to Hawkins’ court-martial and death sentence and the changes that trial sparked in the military justice system.

That acknowledgment isn’t justice, but it’s a step forward, Holt said.

“Initially, it was a very well-concealed fact what took place in 1917. It was not talked about, but many family members, including ones that are here today, we’ve been advocating,” he said. “The approach today is to work collaboratively with the administration, and hopefully, we’ll get some level of clemency that will come about through their good graces.”

Hawkins wrote the letter to his mother and father on Dec. 11, 1917, the day that he was hanged.

“When this letter reaches you, I will be beyond the veil of sorrow. I will be in heaven with the angels,” Hawkins wrote. “I'm sentenced to be hanged for the trouble that happened in Houston, Texas, although I am not guilty of the crime that I'm accused of. But mother it is God's will that I go now and in this way.”

Holt, an attorney in New Jersey, read from the letter during Tuesday’s ceremony about a sign meant to educate cemetery visitors on the events known as the Houston Riots and the Camp Logan Mutiny of 1917.

From left, Jason Holt, nephew of a soldier executed in 1917, Matthew Quinn, undersecretary for memorial affairs with the Department of Veterans Affairs, Donald Remy, deputy secretary of VA, and Gabe Camarillo, undersecretary of the Army, stand Tuesday at a newly unveiled sign to commemorate the history of 17 soldiers buried at Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery in San Antonio after they were executed for their role in a race riot in Houston in 1917. The sign acknowledges the trials of the soldiers were “flawed by serious irregularities.” (Rose L. Thayer/Stars and Stripes)

“To many, the Houston Riots is simply a footnote in history,” Holt said. “But for us, the family members, it’s a little different. For us, it's a time when we know that we lost someone dear to our family.”

Hawkins was a soldier from North Carolina assigned to the 3rd Battalion of the 24th Infantry Regiment. It was a unit of the Buffalo Soldiers, the nickname given to Army regiments of Black troops who served beginning in 1866.

In the summer of 1917, the battalion was sent to Houston to guard Camp Logan, one of many training sites that the Army established during World War I. Racial tension began immediately between the Black soldiers and white Houston police officers, through ongoing slights and open hostility that built into a volatile situation.

On Aug. 23, 1917, racial tensions boiled over, culminating in a two-hour riot through the city. Four soldiers and 15 white civilians and police officers died.

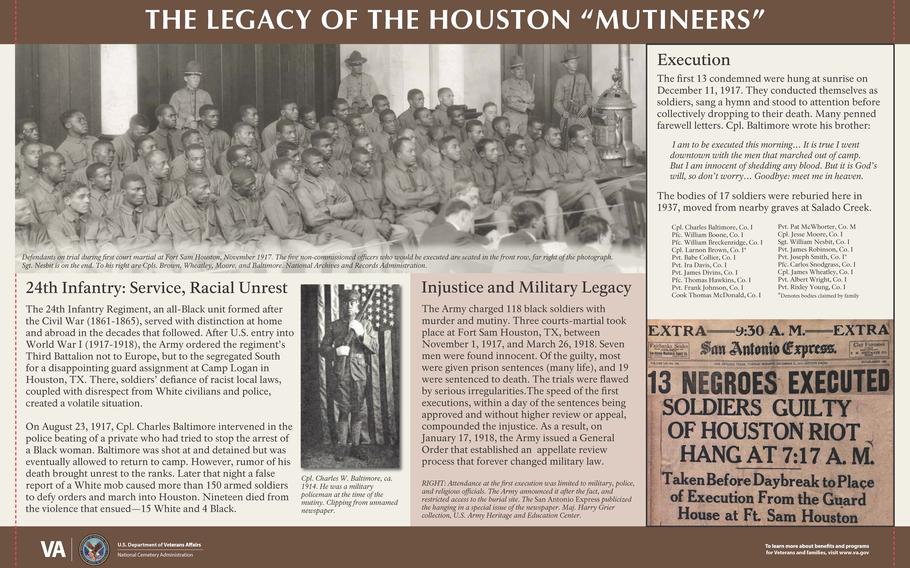

By December, the Army orchestrated the first of three courts-martial at Fort Sam Houston for 118 Black soldiers charged with mutiny and murder, among other lesser charges. They were all represented by one Army officer who had some legal experience but was not a practicing attorney. After the three trials, 19 soldiers were hanged, including Hawkins.

Seventeen of those 19 men were eventually buried at Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery under gravestones that only bear their names and death dates, which was customary at the time for executed soldiers. The gravestones stand in contrast to those around them because they lack rank and service branch, birth dates and any wars in which the troops served.

Of the 19 soldiers found guilty of mutiny and hanged following the Houston Riots of 1917, 17 are buried at Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery in San Antonio, Texas. The Department of Veterans Affairs unveiled a new sign Tuesday that tells the story of these men. (Rose L. Thayer/Stars and Stripes)

The sign installed Tuesday at the cemetery states the trials were “flawed by serious irregularities.”

Earlier this month, the Army began a review process of the trials, which could result in clemency for some or all the soldiers. The request to review the case came not just from family members of those who died, but also retired general officers, said Gabe Camarillo, undersecretary of the Army, who attended Tuesday’s event alongside Donald Remy, the deputy VA secretary, and three descendants of soldiers who were hanged.

“Thanks to the very rich and deep historical record, there's ample documentation that they can currently undertake to review it to provide that broader context,” Camarillo said. “At the conclusion of that process, the Board of Correction of Military Records will make recommendations to the secretary of the Army for any relief that would be appropriate.”

Remy said if any outcome of the Army’s review calls for an update to the sign, the VA will do so.

A two-foot-by-three-foot sign installed Tuesday at Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery, Texas, describes a 1917 race riot in Houston that involved Black soldiers of the 3rd Battalion of the 24th Infantry Regiment. The Army charged 118 soldiers for their roles in the riot and 19 were executed. Of those who were hanged, 17 are buried at the cemetery. (Graphic provided by the Department of Veterans Affairs)

Entering a ‘powder keg’

When the battalion arrived in Houston, they entered what civil rights activist Malcolm X would have referred to as a “racial powder keg,” said James Jones III, an associate professor of history at Prairie View A&M University, located northwest of Houston.

Military service was one of the few professions available to Black men during that time that would allow them to build a career. But uniformed Black men were also a target of white aggression, he said.

“The Camp Logan incident is so representative and emblematic of America at this time. You have to remember that the 24th [Infantry Regiment] had actually served internationally. They had been in Cuba [and] they participated in a Spanish American War,” Jones said.

Many of them said they experienced less racism during those deployments than they did at home, which builds the context surrounding the Houston Riots, Jones said. So, the soldiers were not prepared for the level of hatred awaiting them in Houston.

“It was truly a different situation, more intense than they had ever experienced,” Jones said.

On the day in August when the riots broke out, it began with the arrest of a Black woman by white police officers, Jones said. A private from the battalion intervened and offered to help in her, but the police officers beat him and arrested him. Cpl. Charles Baltimore goes to inquire about the private, only to be beaten and arrested himself.

Jason Holt speaks Tuesday during a ceremony at Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery in San Antonio, Texas, about his uncle, Pfc. Thomas Hawkins. The soldier was one of 19 hanged for mutiny after the Houston Riots of 1917 and wrote to his family that he was innocent before his death. The Army this month announced it would review the trials. (Rose L. Thayer/Stars and Stripes)

Rumors circulate at Camp Logan that Baltimore had been murdered, which caused members of the battalion to react, Jones said. At about the same time, soldiers believed a group of armed white people were heading toward the base. The situation devolved, soldiers took arms, and what was meant to be a march to police headquarters became a riot.

Afterward, the Army sent the unit to Fort Sam Houston, where the mass courts-martial began. In one, 63 soldiers were tried at once, making it the largest court-martial in U.S. military history, said Richard Hulver, historian for the VA’s National Cemetery Administration.

The first trial lasted 25 days with about 200 witnesses, he said. It had to be held in the post chapel because the courtrooms weren’t large enough to hold that many people. Some soldiers were coerced to testify against other soldiers, and, in the end, it was never clear who had fired shots that killed.

The court-martial resulted in 13 men found guilty and hanged one day after the verdict was approved. All were hanged at once before sunrise and buried next to the gallows in numbered graves. Each was buried with a glass bottle with their name inside.

Two more courts-martial followed, and six more soldiers were hanged. Two men’s bodies were returned to their families.

Of all 118 men on trial, seven were acquitted, while others found guilty received various prison sentences.

Angela Holder and Charles Anderson, far left, recite the pledge of allegiance during a ceremony Tuesday to unveil a sign about the Houston Riots of 1917. The two are descendants of two of the 19 soldiers hanged for mutiny following the riots. (Rose L. Thayer/Stars and Stripes)

The public reacts

“The legacy of the first court-martial was, there was such a public outcry about that, the Army changed its appellate process,” Hulver said. “Their burial site becomes a site of public interest immediately. People start coming, and the Army actually has to put guards up to keep people out.”

In 1937, visitors to the site became such a problem that Maj. Gen. James K. Parsons, the commander of Fort Sam Houston, had the soldiers’ bodies moved to the cemetery, which was then under the Army’s command. The commander marked each grave with the headstone allowed for executed soldiers under the policy for the time.

President Woodrow Wilson stepped in following the third trial, commuting the sentences of 10 soldiers from death to prison, Jones said. In his statement, Wilson also said the trials were properly handled and all investigations were thorough.

“On the one hand, he’s soothing the white conscience, that we got them. But at the same time, he's telling Black soldiers, ‘We appreciate your work.’ It's one of those classic examples of serving two masters. He does it well. It was very admirable,” Jones said.

The Army did not include a timeline for their review of the cases.

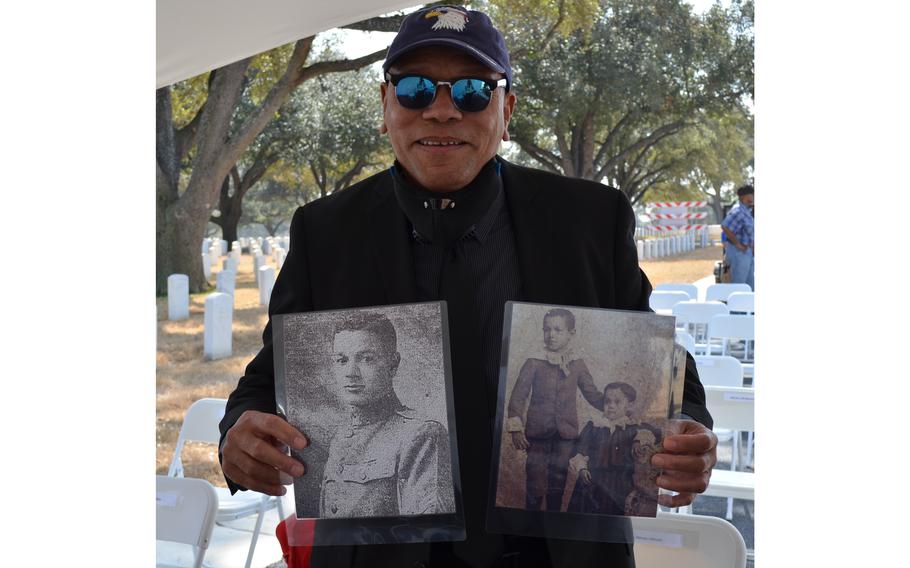

Charles Anderson, a Texas-based distant cousin of Sgt. William Nesbit, another soldier hanged for mutiny in 1917, attended Tuesday’s ceremony. Anderson brought with him a photo of Nesbit’s grave, where he’d written in marker the soldier’s full military service on the headstone. Like Holt, he would like to see his relative’s name cleared.

Charles Anderson holds photographs of his cousin, Sgt. William Nesbit, who was one of 19 men hanged for mutiny following the Houston Riots of 1917. Anderson and other descendants of the soldiers have been advocating for the Army to review the case. This month, the Army announced it would do so. (Rose L. Thayer/Stars and Stripes)

Anderson said he first learned of the Houston Riots and his relative’s involvement when researching Nesbit’s grandfather. On his path to learn about the history and educate others, he’s connected with the descendent of a white Houston police officer killed in the riot.

“Coming here to just be a part of something that's actually recognizing these guys is just amazing. It’s amazing to know that they're getting this attention right now,” Anderson said.

Remy, the VA’s deputy secretary, said the ceremony and addition of the sign is just a “small measure of the dignity” that these soldiers have long deserved because their service was marred by racial injustice.

“This day, in some small way, reflects the progress that we have made as a nation since these men were interred here,” he said.