Rep. Sanford Bishop, D-Ga., right, and Army Lt. Gen. Ted Martin, the commander of the Army’s Combined Arms Center reveal a historical marker in remembrance of Pvt. Felix Hall at Fort Benning, Ga. on Tuesday, Aug. 3, 2021. In 1941, the 19-year-old Hall, a member of the Army’s Black-only 24th Infantry Regiment, was lynched on the Army post. He is the only known victim of a lynching on a U.S. military installation. (Corey Dickstein/Stars and Stripes)

FORT BENNING, Ga. — It was more than 80 years ago that Pvt. Felix Hall, an outgoing teenage soldier training to serve his country in war, disappeared as he made the short walk from his workplace on Fort Benning toward the Blacks-only section of the segregated Georgia Army post.

Hall’s body, bound at the hands and feet and already beginning to decompose, would not be located for six weeks, hanged from a small tree in a shallow ravine in a wooded section of Fort Benning’s training grounds less than a mile from where he was last seen. The 19-year-old had been the victim of a lynching — the only one known to have ever occurred on U.S. military grounds, and likely at the hands of his fellow soldiers.

For the first time, the Army is telling Hall’s story by erecting a historical marker Tuesday at the location where on Feb. 12, 1941, he was last seen alive. The spot today sits just off the jump training grounds of the Army’s airborne school at the busy intersection of Merchant Avenue and Edwards Street, and within a short walk of the post’s massive headquarters building, home of its Maneuver Center of Excellence. Army officials said they plan to add the marker’s location and the nearby site where Hall’s remains were discovered to Fort Benning’s official historical tours.

“I wish today felt like we were righting a wrong,” said Army Lt. Gen. Ted Martin, the commander of the service’s Combined Arms Center at Fort Leavenworth, Kan. He traveled to Fort Benning, where he had served previously, to attend Tuesday’s event. “But I know that what we are really doing is just acknowledging one.”

For Rep. Sanford Bishop, D-Ga., the long-serving congressman and Army veteran whose district includes Fort Benning, the acknowledgement is a strong start at properly memorializing Hall. He hopes by sharing Hall’s story that Americans can learn the dangers of racism and hate.

“I think the Department of Defense is setting a very, very positive example [by] recognizing the indignities suffered by Pvt. Hall, even at this point 80 years later,” Bishop, who helped organize Tuesday’s event, said recently. “It was a horrendous situation. And it's a reminder, really of the lessons that we have to learn in the context of how far we have come, but how much yet we have to do in order to get to a point of equity and justice, and to really realize the kind of country that we all would like to have, as has been said, so often — of a more perfect union.”

The ceremony honoring Hall and the Army’s official recognition of the lynching comes as the United States has faced a renewed racial reckoning in the 14 months since George Floyd’s murder at the hands of a then-Minneapolis police officer.

As new movements seeking racial justice — among the largest since the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s — swept across all 50 states in the summer of 2020, the Pentagon renewed its own efforts to ensure racial equality within its ranks. Then-Defense Secretary Mark Esper ordered studies aimed at ensuring Black and other minority service members had the same opportunities to advance in rank as their white peers, after past studies showed few Blacks, especially officers, reached the highest ranks of the military.

Since President Joe Biden’s inauguration, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin has added new efforts aimed at rooting out white supremacy and other extremist activities in the ranks. Austin, a retired Army four-star general and the first Black defense secretary, also has endorsed efforts to rename Army installations across the southeast named for Confederate Civil War generals — including Fort Benning, which was named in 1918 for little-known Confederate Brig. Gen. Henry Benning, who was best known as an ardent defender of slavery and secession.

Fort Benning, and the nine other Army bases named for Confederates, will be renamed within the next three years, Congress ordered in legislation passed last year.

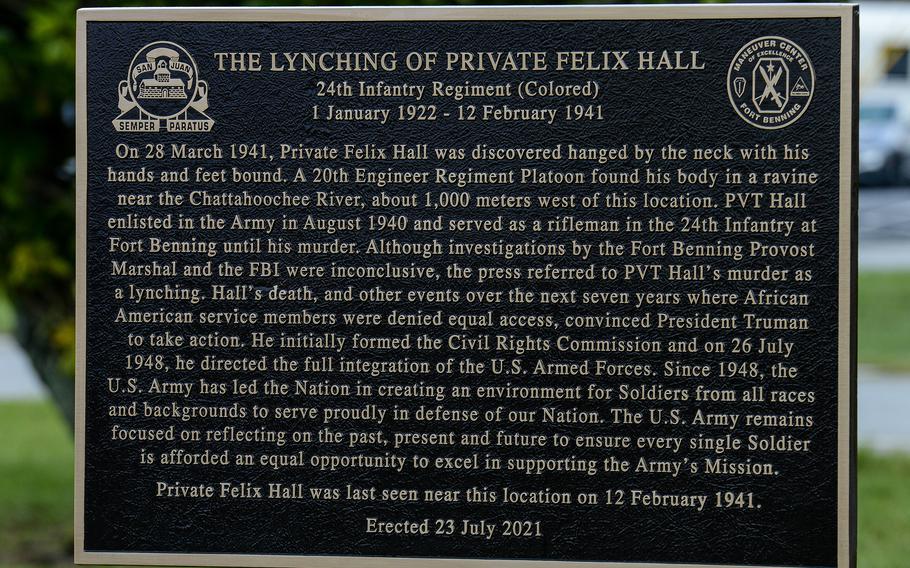

A historical marker in remembrance of Pvt. Felix Hall at Fort Benning, Ga. was revealed for the first time on Tuesday, Aug. 3, 2021. In 1941, the 19-year-old Hall, a member of the Army’s Black-only 24th Infantry Regiment, was lynched on the Army post. He is the only known victim of a lynching on a U.S. military installation. (Corey Dickstein/Stars and Stripes)

Who was Pvt. Hall?

Inspired by his cousins who had joined the Army a few years earlier, Felix Hall was 18 years old when he traveled the 11 miles from his native Millbrook, Ala., to a recruiting station in Montgomery, Bishop said Tuesday, citing federal records. There, he enlisted in the service and was shortly on his way to Fort Benning, some 100 miles east of his hometown, where the Army was training an all-Black unit, the 24th Infantry Regiment, which would eventually be sent to the Pacific Theatre to fight in World War II.

The Army was seen by many as one of the few ways out of small-town Alabama, where picking cotton and hard labor were the only job opportunities, Bishop said. After arriving at Fort Benning, Hall was assigned to work at the post’s sawmill when not training for combat.

He was known as outgoing, friendly and well-liked by his peers, investigations of his death by the FBI and War Department — as the Defense Department was known then — revealed. Some of his fellow soldiers labeled him flirtatious with women, including at least three back home in Alabama with whom he regularly communicated.

He appeared to be a good soldier, said Bishop, citing the heavily redacted 130-page FBI report into Hall’s death. His office has requested the full, unredacted report, but the FBI has denied its release arguing it would constitute an “unnecessary invasion of privacy.”

Hall’s life was cut short just some six months after arriving at Fort Benning. On Feb. 12, 1941, just 43 days after his 19th birthday, the soldier went missing as he walked from his job at the sawmill through a white neighborhood directly between his job site and the “colored section” of the post where he lived.

The Army considered him absent without leave for the six weeks that Hall was missing, until a unit training in a wooded area on post discovered his body. Despite the fact his hands and feet were found bound and there were signs Hall attempted to escape, service officials initially ruled his death a suicide. A medical examiner and the FBI later determined he was murdered, likely by multiple individuals, according to the investigations.

'Never again'

Hall’s killing remains unsolved. But his case might have made an impact decades ago on the military. According to the Army, it was one of a several cases that convinced President Harry Truman to desegregate the military in 1948.

In the decades that followed, his killing was largely unremembered until 2016 when The Washington Post published a story on Hall’s murder, citing the work of Northeastern University Law School’s Civil Rights and Restorative Justice project, which memorialized some 1,100 killings in the Jim Crow south motivated by race, including Hall’s.

Army officials acknowledged at the time that its top leaders did not know of Hall’s story. Even Bishop, who has represented Fort Benning’s district since 1993, was unaware of the killing or that any lynching had ever occurred at the base.

He was made aware of Hall’s story only when a constituent, a former soldier, reached out to ask what was being done to remember Hall in the years after reading The Washington Post story. The answer at that time was simple — nothing.

Now, Bishop hopes soldiers and others who spend time at Fort Benning will visit the marker noting Hall’s tragic death. Fort Benning has erected a temporary marker in the wooded area where Hall’s body was discovered and plans to place a permanent, granite marker at the location in the coming months.

“It's important, particularly with the challenges racially that our country is experiencing now, for us to really realistically and honestly look at our past, look at our history, look at the things that have happened, look at the warts on our country, and recognize them for what they are and what they were,” Bishop said. “That’s the only way we can be sure that we try to never repeat them.”

While Hall’s case — including the identities of the culprits and their motivation — remains a mystery, Bishop said Tuesday that he hoped that by highlighting his tragedy, federal investigators would take a fresh look at the case, even as the congressman recognizes there’s little, if any, chance any of the killers are alive.

“At some point, I believe that that investigation will be pursued, and I think that the truth will come to come to light,” Bishop said. “I think that it's important that the truth be known, and, yes, I think that the investigation should be pursued.”

Martin, the Army general, noted the progress that the Army has made on racial issues since Hall’s lynching, but he said the Army’s past failure to acknowledge Hall had done a disservice to soldiers.

“Since then, as a nation, we’ve made incredible progress, but we can’t be satisfied until we have a generation that fully represents all elements of our population serving this country in uniform,” Martin said. “Then they can look at this marker we [unveiled] today and say to themselves, ‘Never again in my country. Never again in my Army.’ ”