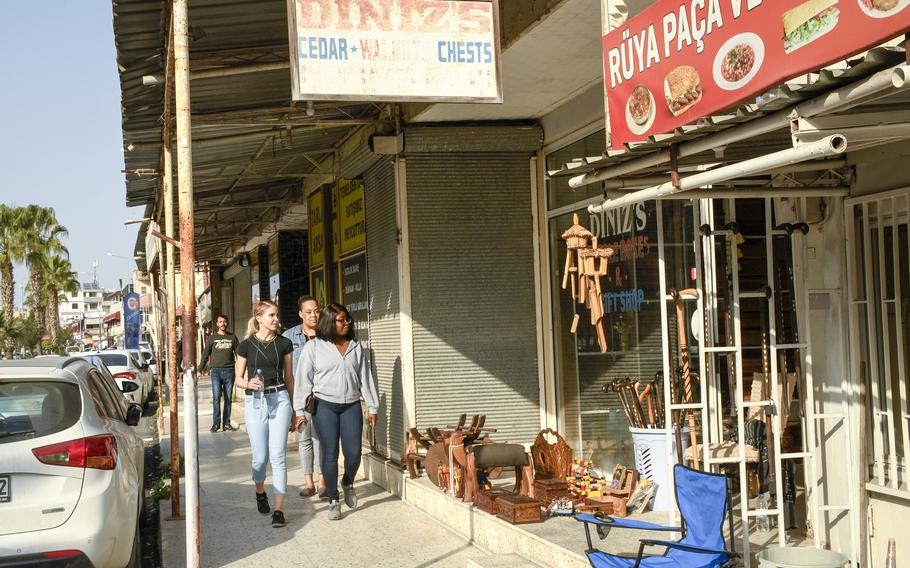

Master Sgt. Jessyca Boyd, front right, examines wares for sale along an area known as American Alley outside the gate of Incirlik Air Base in southern Turkey on Feb. 27, 2023. (J.P. Lawrence/Stars and Stripes)

INCIRLIK AIR BASE, Turkey — Persistent offers of apple tea and business cards greet U.S. troops leaving this small base in southern Turkey, as shopkeepers from newly reopened storefronts politely but aggressively court American dollars.

The air wing at Incirlik Air Base, which has been at the forefront of earthquake relief in the region, ended years of isolation in late January when it began to let airmen visit the nearby community outside the gates.

U.S. troops were forbidden from leaving the base in 2016, when deteriorating security in the area led to the Pentagon ordering nearly 700 military family members to leave Incirlik and two smaller military installations in Turkey.

Recent efforts at the base mark a transition away from a deployment experience like those normally found at more remote bases.

The commander of the 39th Air Base Wing said Thursday that he hopes interacting with people off-base can improve relations between the U.S. and Turkey, and make an assignment to Incirlik more appealing.

Diniz Murat tells Tech. Sgt. Jasmine Helm-Lucas to stand on one of his wooden puzzle boxes to demonstrate the durability of his wares on Feb. 27, 2023, in a shop near Incirlik Air Base in southern Turkey. (J.P. Lawrence/Stars and Stripes)

“It was important for me to reinvigorate that interaction and positive influence on the community,” Col. Calvin Powell said.

The earthquakes that struck the region beginning Feb. 6 and killed more than 50,000 people in Turkey and Syria put a pause on the base’s efforts to open up, as troops grappled with handling a surge of humanitarian aid from around the world.

The airmen can’t yet go to most parts of Adana, a city with a metro population of about 1.8 million that lies 8 miles to the west. This is due to safety concerns and out of respect to citizens recovering from the earthquakes, Powell said.

Last year, travel restrictions for airmen began easing, with some trips to nearby sites and cities authorized. Starting January 20, airmen were allowed to go to “American Alley,” a 10-block area southeast of the base. It’s similar to districts near other overseas U.S. bases, with trinket and furniture shops, hookah bars, a fried chicken stand and restaurants serving beer.

Some U.S. troops seen on a recent walk through American Alley said they welcomed the chance to explore.

“I did not want to come here before I knew you could go off the base,” said Tech. Sgt. Jasmine Helm-Lucas, as she examined wares from a gift shop.

Vedat Tan twirls an Afghan rug, colored blue with indigo dye, at his shop in an area known as "American Alley" outside the gate of Incirlik Air Base in southern Turkey on Feb. 27, 2023. Tan said recent earthquakes forced him to live in his car for almost two weeks, and that neighbors died in the disaster. (J.P. Lawrence/Stars and Stripes)

Airmen here serve one-year tours, unaccompanied by their families. But the prospect of travel “softens the blow,” said Master Sgt. Jessyca Boyd.

Some of the area’s merchants have stocked what they assume Americans want, including John Wayne and Bob Marley art, as well as leather jackets with pistol holders.

Among the more ostentatious gimmicks to gain foot traffic includes one shopkeeper’s invitation for the customers to jump on top of his wooden jewelry boxes to demonstrate their durability. One carpet seller launches his rugs into the air, where they spin before landing and rotating on the shop’s floor.

Hakan Bindal, who engraves commemorative plaques and award coins, said he’s been studying American football rivalries as a way of building rapport with his customers.

If someone wants a coin emblazoned with the logo of an NFL team, he’ll jokingly give them a coin from a team they hate, usually the Dallas Cowboys.

It’s important to make friends with the Americans, said Bindal, as he left his shop for a smoke. He and other shopkeepers on American Alley have invested huge sums on storefronts next to the base. Bindal’s shop is directly across from the Incirlik exit gate, a prime location costing three times that of another shop four blocks away, he said.

It took nearly $150,000 for the Moonlight Restoran nearby to reopen after closing in 2016, owner Cengiz Durmaz said.

Many of the merchants at American Alley have been there for decades. The U.S. Air Force has been at Incirlik since 1954, and for most of that time, it welcomed families.

Bindal and other shopkeepers recalled working and playing at stores near the base when they were kids. Apart from more gray hair, many of the shopkeepers are the same, said Bindal, 48.

In the 2010s, Incirlik Air Base became a hub for America’s war on the Islamic State group. Concerns of violence in the region led to the end of families moving to the base in 2015, followed by the removal of all family members a year later.

Cumali Palta, a tailor outside Incirlik Air Base in Turkey, shows off a leather jacket with a pistol holster that he hopes will appeal to the U.S. airmen deployed at the nearby base on Feb. 24, 2023. (J.P. Lawrence/Stars and Stripes)

In 2016, a Turkish commander on the base purportedly participated in a coup against President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, leading to the government cutting power to the base and grounding all American flights, The New York Times reported at the time.

U.S. troops began to serve one-year unaccompanied tours. They stayed on base, living in college-style dorms or suburban-style homes with grass and citrus trees in their backyards, sometimes renting scooters to drive to the bowling alley, archery range, golf course or commissary.

Outside the base walls, American Alley withered. Many shopkeepers closed their stores or like Bindal, the engraver, sold goods online. Some took jobs on U.S. bases in Iraq and Afghanistan.

“We would pray,” Bindal said, before raising his hands out wide and upward.

"Open the gate!" he boomed theatrically, before breaking out in laughter.

But after dropping their cheeriness, many of the merchants said they felt deeply uncertain.

Most of the shopkeepers and their families had been affected by the recent earthquakes and were worried another would strike soon.

Aftershocks continue to hit the region. A magnitude 6.3 aftershock hit southern Turkey last week just as many people were ready to return to their homes. Another quake this week killed one and injured more than 100 people, The Associated Press reported.

Vedat Tan, who co-owns a rug shop on American Alley, said he had to live in his car for almost two weeks after the quakes. He and his family lived in apartments in nearby Adana.

Tan recalled rushing out of his apartment and realizing that his neighbors had died when their buildings collapsed.

A recent drive through Adana revealed a city still wounded by the earthquake. Apartments are cracked and fractured, and open gravel pits mark where buildings had collapsed.

A cluster of humanitarian aid tents from Turkey’s national disaster management agency stood in the center of a park in downtown Adana. It is part of a response to the more than 1 million people in Turkey who lost their homes in the quakes, Turkish Vice President Fuat Oktay said recently.

Tan said he no longer feels safe in his home. Others said they cannot sleep without fear, or that they are addicted to watching news about the disaster. Many expressed anger at what they said was the corruption that allowed so much shoddy construction.

Tan hopes upcoming elections in June won’t threaten to close the base again. Opposition parties believe that will be their opportunity to unseat Erdogan, whom they accuse of a lack of earthquake preparedness and a slow pace in providing relief, Politico reported in mid-February.

Some airmen on base said that while they worked hard to facilitate humanitarian aid to Turkey, they weren’t close enough with Turkish co-workers to talk with them in-depth about the earthquakes.

Even those who spoke at length with their Turkish co-workers about the earthquakes acknowledged that they had been insulated from disaster. The base suffered no significant damage.

“I feel safe on base, but our TNs, they are scared for their homes and their families,” said Senior Airman Hailey Klchosky, an airman at the 728th Air Mobility Squadron, using an acronym for Turkish nationals.

The earthquakes struck before airmen on base could forge close ties with the community, said Mehmet Birbiri, the local adviser for the air wing’s public affairs office.

Birbiri, 72, has been working at Incirlik since 1975. He takes a long view on relations between the U.S. and the Turkish community. He doubts ties will be as strong as when the U.S. had families here.

But the airmen still can benefit from making friends outside the base, and from trips to sites like the Taskopru Roman bridge in Adana and the birthplace of St. Paul in nearby Tarsus.

“While they are here, they should learn a new culture,” Birbiri said.

A cluster of tents from Turkey’s national disaster management agency stand in the center of a park in downtown Adana, Turkey, on Feb. 25, 2023. More than 1 million people in Turkey are living in tents following the Feb. 6 earthquakes, Turkish Vice President Fuat Oktay told reporters recently. (J.P. Lawrence/Stars and Stripes)