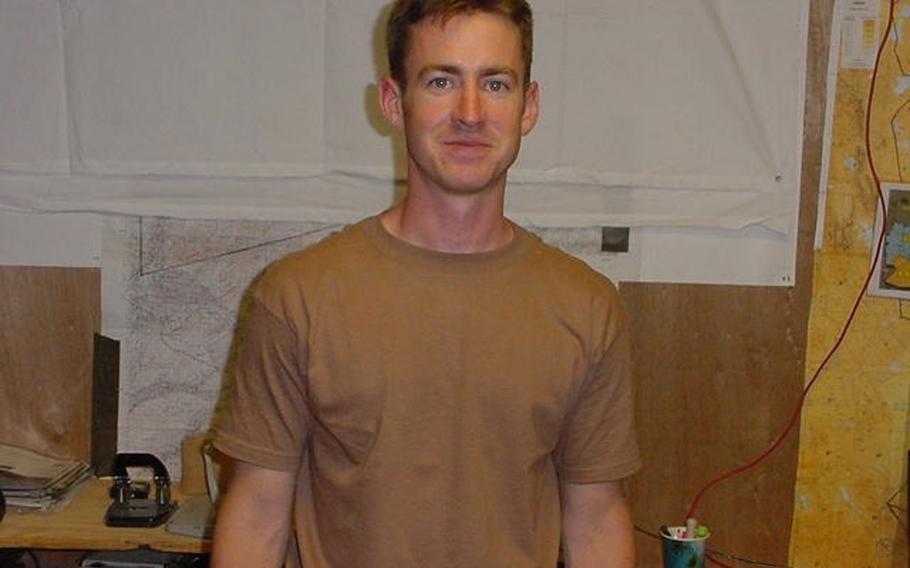

Then-Air Force 1st Lt. Brian Liebenow at Kandahar Air Base in Afghanistan in 2002, where he was serving with the 23rd Special Tactics Squadron. A year earlier, Liebenow was at Karshi-Khanabad Air Base in Uzbekistan. (Brian Liebenow)

NOTE: Photo gallery contains a graphic image.

In the 19 years since he served at Karshi-Khanabad Air Base in Uzbekistan, former Air Force Maj. Brian Liebenow has had at least two types of cancer, lost half his jaw to radiation damage, had one of his arms amputated and eats through a tube in his stomach.

He is one of hundreds of veterans who have come down with cancer and other illnesses after serving at the former Soviet base, which the U.S. used between 2001 and 2005 to support the war effort in Afghanistan.

Defense Department documents declassified last year show the Pentagon knew troops were exposed to multiple toxins at the base, known as K2, and that exposure to those toxins caused hundreds of cancer cases and killed dozens of veterans.

But the Department of Veterans Affairs has denied many of the sick veterans care and disability benefits, often arguing that data don’t conclusively show a connection between their illnesses and their service.

“I ask the VA to please listen to veterans and get this done for all of us,” Liebenow told Stars and Stripes in a phone interview. “Listen and learn before it’s too late. A lot of these people are dying right now.”

In recent months, lawmakers and advocacy groups have been pressuring the VA to provide benefits for K2 and other veterans sickened by exposure to toxins.

Seven pieces of legislation have been introduced in Congress and President Donald Trump signed an executive order about toxic exposure at K2 during his final hours in office. The 2021 National Defense Authorization Act also requires the VA to conduct a study of illnesses and deaths among veterans stationed at the base, with findings due by June 30.

But veterans advocates say the VA isn’t following through. VA officials did not respond to a Stars and Stripes request for comment on the study.

In the 3 ½ months since the NDAA was passed, the VA hasn’t contacted Liebenow or anyone else at the Stronghold Freedom Foundation, a group that seeks to increase awareness of the effects on veterans of toxic exposure at the Uzbek base, about the study.

“It’s like they don’t want to know or they’re choosing not to find the information about toxic exposure,” Liebenow said.

Many of the bills have gone nowhere, said Mark Jackson, a former Army investigator who served in K2, Afghanistan and Iraq and was diagnosed this month with severe osteoporosis. The 43-year-old has had a nonfunctioning thyroid and gastrointestinal issues for years.

“Most of the bills came out of committee, went into conference and got stripped down to, in the K2 bill’s case, a six-month study,” he said, referring to the K2 Veterans Toxic Exposure Accountability Act, introduced in February 2020 by Rep. Mark Green, R-Tenn., a veteran of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

“A lot of these bills give the VA time to look at the evidence,” said Jackson, who is now a federal investigator and chair of the Stronghold Freedom Foundation. “But we don’t have time.

“Half of us who were at K2 are sick and the oldest are in their 50s. I get it – the older we get, the more funerals we go to but none of the ones I go to are for old people.”

On Tuesday, Jackson will be one of several veterans at the launch on Capitol Hill of yet another toxic exposure bill.

But the War Fighters Act, introduced last month by Sens. Kirsten Gillibrand, D-N.Y., and Marco Rubio, R-Fla., doesn’t call for another study. Instead, it wants to establish a service connection for illnesses caused by exposure to toxins.

The bill is written in the same way as the Agent Orange Act of 1991. Rather than requiring veterans to prove exposure to toxins, the War Fighters Act lists diseases known to result from toxic exposure, including several cancers and respiratory illnesses, and requires the VA to presume they were service-connected.

Veterans are optimistic that something positive will come out of the legislation, possibly this year. Comedian Jon Stewart, who helped push through legislation and compensation packages for 9/11 first responders in 2019, is backing the War Fighters Act, and President Joe Biden has said he believes toxic exposure in Iraq killed his son, Beau.

If the bill succeeds, it will mark a bitter victory for some veterans, like retired Tech. Sgt. Douglas Wilson, another K2 veteran.

Wilson has been fighting for years to have the VA recognize that the brain cancer that forced the Air Force to medically retire him in 2013 was a service-connected illness. He can no longer work or drive, and rides an electric wheelchair along the side of the road to his physical therapy appointments. His family is surviving on his wife’s salary as a teacher.

His oncologist has said Wilson’s cancer is “unequivocally” tied to his service at K2, but the VA refuses to recognize the connection.

“They treat (us) like they did the Vietnam veterans,” Wilson said. ”They are trying to deny us until we die.”