-(1).jpg/alternates/LANDSCAPE_910/Europe_District_supported_managed_construction_projects_around_U.S._air_base_3985995069%201.jpg)

This is a 2009 aerial photo of Ramstein Air Base, Germany, the largest hub for U.S. troops and military supplies in Europe. Germany is one of the biggest buyers of Russian energy on the Continent. (Justin Ward/U.S. Army Corps of Engineers)

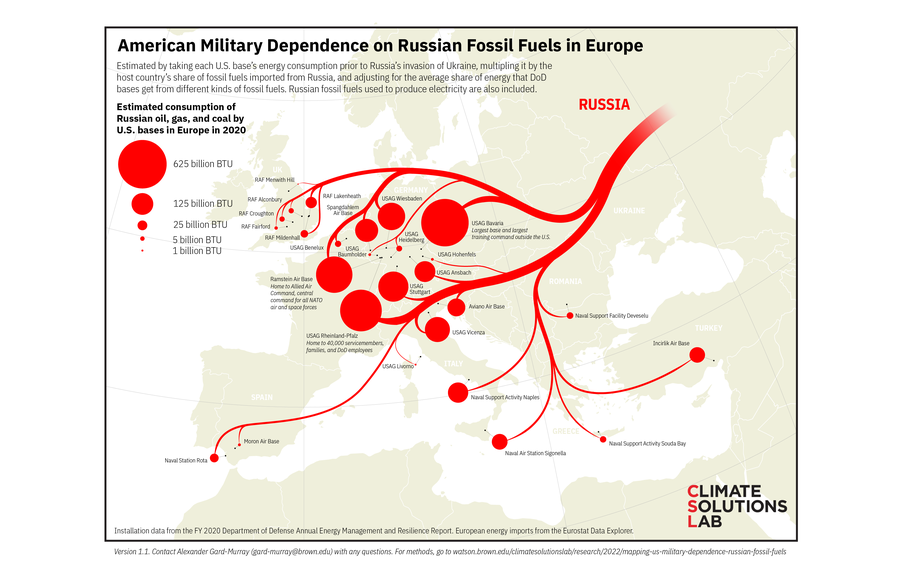

WASHINGTON — Russian fossil fuels have long helped power American military bases in Europe.

Ramstein Air Base in Germany, the largest hub for U.S. troops and military supplies on the Continent, consumes Russian gas to the tune of more than $4 million yearly, according to an April analysis by Brown University’s Climate Solutions Lab. Collectively in Europe, U.S. installations have relied on Russian natural gas, oil and coal for 30% of their energy needs.

That dependency is now partly fueling Russia’s war effort against Ukraine and a renewed push in Congress to reduce the U.S. military’s reliance on Russian-sourced energy. The House’s draft of the 2023 National Defense Authorization Act, an annual must-pass bill that sets policy and spending priorities for the Defense Department, singles out Russian fuel consumption by American forces in Europe and spurs the Pentagon to pursue total energy independence from Moscow.

“In every way possible, we should hinder Russia’s economic and military capability. That’s why it becomes exceedingly important that at the very minimum, the United States military is not engaging in any activity that would support or help the Russian economy,” Rep. John Garamendi, D-Calif., said Monday. “The consumption of Russian fuel by the United States military directly helps the Russian economy and thereby the Russian ability to continue to engage in Ukraine.”

The House legislation requires all main bases in Europe to adopt installation energy plans by June 2023 to reduce reliance on Russian fossil fuels and asks the Pentagon to eliminate the usage of Russian energy entirely no later than five years after the plans are completed.

“It is the sense of Congress that reliance on Russian energy poses a critical challenge for national security activities in the area of responsibility of the United States European Command,” the provision states.

The Defense Department also would be required under the legislation to factor in energy security and resilience when opening any new U.S. military bases in Europe. Additional amendments proposed by lawmakers last week call for assessments of a base’s capacity to replace Russian energy with energy produced in the U.S. and the establishment of a program to help wean Europe off Russia’s fossil fuels.

Garamendi, who is the chairman of a House subpanel overseeing military installations, said he is confident Europe is moving in the right direction after meeting with representatives from several countries — including Poland, Bulgaria, Finland and Sweden — at an annual session last week of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. Congressional directives to divest from Russian energy are meant to complement Europe’s efforts to do the same, he said.

“The overarching issue here is that the United States military will be working in a coordinated way with our NATO allies in reducing and eliminating the consumption of Russian fuel,” Garamendi said.

Last year, Russia provided 45% of the European Union’s natural gas imports and 27% of the bloc’s oil imports, Amos Hochstein, the State Department’s senior adviser for energy security, said last month in testimony to senators. Some European countries are almost entirely dependent on Russian energy sources, he said.

Researchers estimated in April that Russian energy use on U.S. military bases could mean American taxpayers are inadvertently funneling $1 million to Russia’s war machine per week. That figure has fluctuated in the last few months as Russia cuts off gas supplies to nations that do not comply with Russian President Vladimir Putin’s demand for payment in rubles.

()

“The money we spend to run our bases, to keep our troops heated, keep them cool, keep our machines running, the money we’re spending to do that, some of it is going to Russia,” said Alexander Gard-Murray, a post-doctoral fellow at the Climate Solutions Lab at Brown University. “As long as we’re dependent on fossil fuels, we’re going to aid Putin and we’re going to have this Achilles’ heel.”

Lt. Col. Theodore Shanks, an Air Force officer and former defense fellow with Brown University, said Russian fuel dependency on military bases is most pronounced in Germany, which is home to the highest number of U.S. troops in Europe. Germany relied on Russia for almost half of its gas prior to the war in Ukraine and still draws 30% of its gas supplies from Russia despite sanctions against Moscow.

U.S. military installations overseas are heavily dependent on their host nations for energy sources, Shanks said.

“Any requirements for your war-fighting capability that are outside of your control, especially something as vital as an energy source, is very concerning,” he said. “Regardless of how it’s being withheld or how it’s out of our control, it’s something that should demand attention.”

Lawmakers have worried for years that Russia would leverage its fossil fuel exports to intimidate countries and manipulate or disrupt energy supplies, potentially compromising power on U.S. bases. The 2018 NDAA directed the defense secretary to ensure installations could sustain operations in the event of a disruption. In the 2020 version of the legislation, Congress prohibited certain bases in Europe from hiring contractors who source energy from Russia.

The Kremlin’s offensive in Ukraine brought a heightened urgency to build on those efforts. Garamendi said House lawmakers want the military to rapidly develop alternative energy sources for its installations and ultimately transition all 1,100 American bases around the world to clean energy.

“By reducing reliance on fossil fuels, that also reduces the demand for Russian fuel or any fuel for that matter,” Garamendi said.

The Defense Department already has demonstrated a willingness to make that switch through investments in solar panels and other forms of sustainable energy, Shanks said. The Air Force is notably piloting a small nuclear reactor system at the Eielson Air Force Base in Alaska that would allow the base to function independently of a 70-year-old, coal-fired power plant, he said.

Other technology, such as microgrids, can allow a military base to isolate from a civilian power grid and avoid giving a foreign country control over its energy supply, Gard-Murray said.

“We need to invest in alternative energy sources, power more of our bases with renewables, shift more to electric vehicles and to electric appliances on bases,” he said. “Only if we make a serious effort to shift away from fossil fuels can we reduce that dependence on Russia.”

Congress will need to take on a more aggressive role to make that happen, Gard-Murray added. Politicians seldom discuss the extent to which the military depends on fossil fuels and how that creates vulnerabilities with a hostile supplier such as Russia, he said. They have also delayed addressing the issue with the speed that it requires.

“The best time to start was 30 years ago but the second best is today,” Gard-Murray said. “We can still make our bases energy independent. … Congress just needs to pony up the money so it actually happens quickly. It’s not too late but we need urgency.”