Capt. Edward Perez, then a first lieutenant, moving across the berm from Kuwait into Iraq for the first time in 2004. (Courtesy of Edward Perez)

This article was part of Stars and Stripes’ 2010 special five-day report “The Long Goodbye,” published as a five-day series August 16-20, 2010, as U.S. combat troops exited Iraq. Stars and Stripes wrote about the series:

“As he launched the U.S. invasion of Iraq on March 19, 2003, President George W. Bush laid out America’s goals: ‘to disarm Iraq, to free its people, and to defend the world from grave danger.’ More than seven years later, whether the mission has finally been accomplished is far less clear. [In this series,] Stars and Stripes looks at the costs of the war through the eyes of Iraqis and Americans and asks: What difference did we really make?”

BAGHDAD — When Edward Perez arrived in Iraq, he knew he wanted to leave with a Combat Infantryman Badge, his personal measure of success.

It was early 2004 and the main push into the country had just concluded. Perez was a 32-year-old lieutenant with the Texas Army National Guard, assigned to the 1st Cavalry Division and serving in Baghdad and Fallujah. At the time, the situation was calm, and it looked like he had missed his chance to face the enemy.

“The bad part of being a young infantry officer is that you think your goal of life is to be in combat,” said Perez, who is now a captain and again serving in Iraq. “But you really don’t know what that means until you’ve seen it for the first time.”

It was not, Perez discovered, all adrenaline and adventure.

Instead, he felt the frozen bewilderment that comes when the first mortar explodes in front of you.

“My platoon sergeant was like, ‘Sir, what the hell are you doing? Get moving!’ ” he said.

He heard the crack of enemy gunfire directed his way and returned that fire. There was the horror of seeing one of his soldiers injured and the inspiration of seeing another step into harm’s way to help.

“The most amazing thing I saw was a female picking up a wounded soldier,” he recalled. “She was 5-foot-3. He was 6-foot-something, 200 pounds. With her armor on, with her weapon, she got him out of the line of fire in a combat situation.”

Perez did receive his Combat Infantryman Badge. But his small personal victory paled when compared to the larger cost.

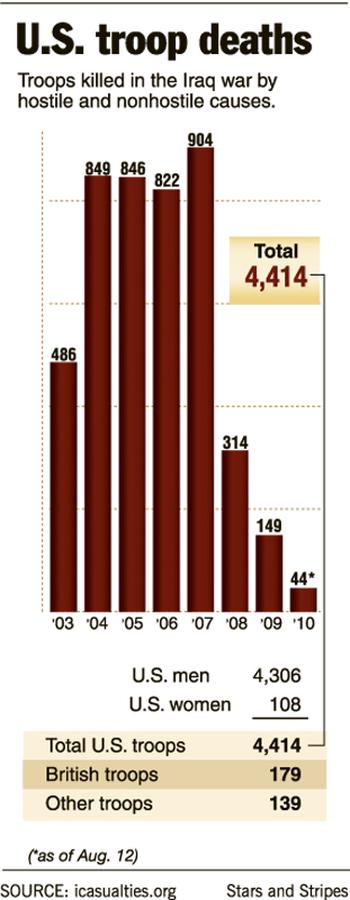

In Iraq, 4,414 American troops have been killed and 31,896 were wounded as of Thursday in a war that was supposed to be quick and easy, but lasted more than seven years.

“The first casualty was very hard,” said Perez as he recalled hearing word of a comrade’s death over the radio in early 2004. “This was a friend we were talking about, not some number. There have been a lot of sacrifices.”

Redefining success

The long war in Iraq offered few of the traditional measures of military success. There was no pivotal battle or unconditional surrender or peace treaty. So the more than 1 million American soldiers who served there were left to create their own individual definitions of success and sacrifice.

For some, victory was defeating an ambush or surviving a roadside bomb. For others, it was getting a new school built in a far-flung village, or persuading a fearful tribal leader to open his door to a patrolling platoon.

‘’You think your goal of life is to be in combat. But you really don’t know what that means until you’ve seen it for the first time,’‘ says Capt. Edward Perez. (Michael Abrams/Stars and Stripes)

For Perez, 41, his personal victory came from the Iraqis themselves, in the slow transformation he saw in the faces that greeted him.

During early patrols around the country, Americans were open targets and the hatred was palpable.

“It was directed at me, and I felt very disturbed by it in the beginning,” said Perez, of San Antonio. “Before, you could see the fear in these people’s eyes. When they saw us coming down the road, they would run.”

Not so today, said Perez, whose second Iraq deployment will end this month. Hostility gave way to tolerance of the troops’ presence.

“I think it is impressive to see the amount of effort that has gone into making this place secure,” he said. “It is just amazing the difference in the people you see.”

That transformation, however, wasn’t without pain. To earn the Iraqis’ trust, troops moved closer to population centers, taking on greater risks and losing lives in the process.

The war was filled with other sacrifices. Many soldiers were stretched to the limit; more than 140,000 were stop-lossed and forced to continue fighting longer than they ever signed up for. Tour extensions challenged units and family members already suffering under the strain of repeated deployments.

The psychological trauma left unseen scars: post-traumatic stress disorder, alcohol and drug abuse, an epidemic of military suicides.

For each American who came to Iraq, there was a different war to fight.

There were fierce battles for cities like Fallujah. There was the monotony of daily patrols in more remote locations, where often the enemy was boredom punctuated by the occasional roadside bomb.

And the foe was ever-changing, morphing from Saddam Hussein’s army to foreign fighters to Shiite militias and Sunni insurgents. At times the Americans were their own worst enemy, as with the scandal at Abu Ghraib prison, where Iraqi detainees were humiliated and abused by their U.S. guards.

Maria Perez and her husband, Capt. Edward Perez, on R&R leave from Afghanistan in 2006. (Courtesy of Edward Perez)

Through it all, the majority of the troops quietly fought on, undermanned and undersupplied.

Perez and others like him took solace in at least one clear-cut victory.

“I do know Saddam Hussein was a bad man. That fact alone — that he was judged by his own people — is a good consequence,” Perez said. “Before they could not stand up to him. After we got here they could.”

Change in the Guard

Bringing the Iraq war to an end required more than the deployment of active-duty troops. Some 218,000 Guard and Reserve troops poured into Iraq throughout the course of the war, many serving multiple tours.

For Perez’s Texas Guard, the Iraq war has meant the largest mobilization since World War II.

During the long fight, the Guard stereotype of “weekend warriors” faded into the sand.

“They were really untrusting of us at first,” Perez said of his active-duty counterparts. “In the old days, training at Fort Hood, there were nasty comments. That’s how it was back then. There aren’t any more comments like that now because the Reserves and National Guard have played a very important role for what the regular army is doing. The mission [in Iraq] couldn’t have been accomplished without us.”

The change in the Guard has been significant: It has evolved into an expeditionary fighting force. Waging wars in foreign lands wasn’t always part of the job description. Now, frequent deployments are a part of life, and those changes have challenged the Guard’s ability to manage home-front responsibilities and respond to domestic emergencies, such as Hurricane Katrina.

“The National Guard feels like it is a battle-tested, hardened organization now with combat veterans,” said Maj. Gen. Bill Etter, director of domestic operations for the National Guard Bureau in Arlington, Va. “It has not been easy, but it has been doable.”

Life changed quickly for Guard members after Sept. 11. Perez was activated that October, and like many others, the years since have been a blur of deployments and extended training missions.

Perez is still angry about Guard members who took a quick out, opting to leave the service instead of deploying, when it became clear that things had changed.

“I lost respect for men that got out after 9/11,” Perez said. “Some of them I called my friends. I don’t call them my friends anymore.”

Life on hold

A music teacher in his civilian life, Perez is working on a master’s degree in psychology and hopes to become a school counselor. But all that had to be put on hold. It’s been hard to find the time for anything but the Guard during two Iraq tours, a deployment to Afghanistan in between, and training for each. Perez’s wife estimates he’s been away from home a total of five years since 2001.

Though they’ve been married eight years, Maria Perez still considers herself a newlywed after spending so many years apart. The toll has been huge: experiencing deaths in the family alone and fearing the worst through many sleepless nights. During a medical consultation after a miscarriage, a doctor asked Maria and Edward if they had any stress in their lives that could be complicating their efforts to have children.

“We just looked at each other … It’s been hard. And it’s been depressing at times,” she said.

But like so many military spouses, Maria Perez discovered self-reliance she never knew she possessed. She also learned that she had to make the most of every phone call and e-mail.

“For us, talking on the phone for five minutes was a long time,” she said. “You really have to learn how to communicate well because you just don’t have time together.”

As she prepares for her husband’s return, she also finds herself reluctant to think of him as a fixture in the family home. As long as there are troops in Iraq and Afghanistan, nothing ever really feels permanent.

“I’m very excited he’s coming home, and I’m going to scream when he walks through that door,” she said. “But I’m also wondering when he is going to have to go away again.”

Worth the sacrifice

This month, Perez and his comrades from the 72nd Infantry will leave Iraq once again. During this deployment they’ve helped transfer responsibility for securing the Green Zone to the Iraqi army. As they count down the hours, most of the soldiers are anchored to their desks doing paperwork. The days of long, sweaty patrols on the mean streets of Iraq are mostly gone.

This will most likely be the last Perez sees of Iraq. It’s a far different place than it was in 2004, when he was getting shot at in Baghdad or, during a later assignment in Fallujah, watching as Marine artillery and rocket fire lit up the sky.

Perez believes that the difference the military and its troops made in Iraq was worth all the sacrifices.

“Sure, I regret being away from home,” he said. “But how many men can say they’ve stood at the basin of the Tigris and Euphrates and watched where they come together? How many men have dug a well in a village that can help people prosper in their lives?

“I have learned the commonality of humankind around the world,” Perez concluded. “Sure, there is violence everywhere, but there also are people just wanting to be the same. People wanting to live their life and go on and raise their children.”

()