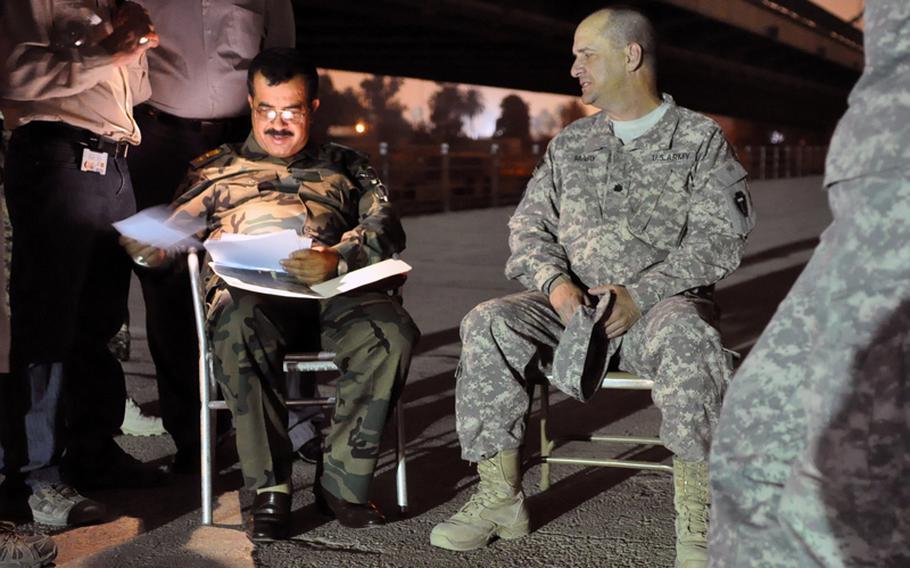

Iraqi army Lt. Col. Abadi Mashkoor Sultan, commander of 1st Battalion, 56th Baghdad Brigade, left, looks at photos from a previous meeting, brought to him by Lt. Col. Gregory McVay, right, security director for the 72nd Joint Area Support Group-Central. The evening meeting to talk about security issues in the International Zone took place on a bridge spanning the Tigris river that connects Baghdad's Red Zone with the IZ, formerly known as the Green Zone. McVay meets Abadi, who commands all Iraqi army troops in the International Zone, on a regular basis. In the background is the 14th of July Bridge. (Michael Abrams/Stars and Stripes)

This article was part of Stars and Stripes’ 2010 special five-day report “The Long Goodbye,” published as a five-day series August 16-20, 2010, as U.S. combat troops exited Iraq. Stars and Stripes wrote about the series:

“As he launched the U.S. invasion of Iraq on March 19, 2003, President George W. Bush laid out America’s goals: ‘to disarm Iraq, to free its people, and to defend the world from grave danger.’ More than seven years later, whether the mission has finally been accomplished is far less clear. [In this series,] Stars and Stripes looks at the costs of the war through the eyes of Iraqis and Americans and asks: What difference did we really make?”

BAGHDAD — Lt. Yussef and Lt. Amir have much in common.

The two 26-year-old Iraqi men hold university degrees in what should have been lucrative fields — computer science and mechanical engineering. But both joined the Iraqi army because they were unable to find work in their chosen professions and the army is one of the few places in this shattered economy where a young man can score a reliable paycheck.

Both men, who asked for anonymity because they are barred by the army from speaking openly, grew up hating the old regime. When the Americans invaded in 2003 and toppled Saddam Hussein, they were certain better days were ahead for Iraq.

Today, however, the two soldiers hold starkly different views about their new government — and the kind of country the U.S. is leaving behind.

Yussef has been impressed by the flexibility of American soldiers, and the U.S. Army’s meritocracy. He wants to stay in Iraq and apply those lessons to his own army, where family connections often still matter more than a soldier’s aptitude or skills.

Amir is so discouraged by Iraq’s pervasive corruption and paralyzing bureaucracy that he hopes to emigrate as soon as he can.

As Operation Iraqi Freedom gives way to Operation New Dawn, the fate of Iraq’s new army could come down to this: Are there more Yussefs in the ranks — soldiers who see something salvageable in Iraq? Or are there more Amirs — men convinced that the nation is so broken it can never be repaired?

Troops with the Iraqi army's 1st Battalion, 56th Baghdad Brigade march in their compound in Baghdad's Green Zone. The unit is responsible for security in the zone. (Michael Abrams/Stars and Stripes)

Yussef: Fighting on

In 2006 — just four days after his wedding — 17 masked men stormed into Yussef’s family home.

Were they Shiite or Sunni, insurgents or foreign terrorists? Or were they simple street thugs?

“I didn’t know who they were,” he said. “They came to our home and demanded that we leave.”

During the confrontation, the masked gunmen killed four workers doing construction on his father’s home. Yussef’s family fled. The young college graduate decided to give up his hopes of an engineering career, at least for a while.

“I made a decision to join the army and do something for my country,” he said.

Since then, he’s worked to help bring more security to Baghdad.

Yussef, who believes the U.S. invasion was necessary for his pariah nation to rejoin the world community, thinks Iraq is now on a path toward normalcy.

“Never forget — [the Americans] got rid of Saddam,” he said. “They’ve opened doors for us to join the world.”

A time will come, Yussef believes, when ordinary Iraqis won’t have to fear a violent death and the bombings that still regularly shake the capital. Eventually, he believes, the Iraqi government will be able to deliver such basic services as reliable electricity and consistently running water.

He says his optimism comes from seeing how far the country has come since 2006-2007, when sectarian conflict was at its worst. When he was a university student, a 20-minute commute to class turned into a three- to four-hour drive because of all the security checkpoints.

“It was a very hard time. We are human, and these things make you mad,” he said.

“But I’m positive. Without hope you can’t do anything. If you want to make changes in the world, you have to be patient — God will help.”

Yussef hasn’t given up on his other ambition. He recently applied to study abroad for an advanced degree with hopes of developing the engineering skills needed to help repair Iraq’s broken electrical grid.

Will his superiors grant him a leave of absence from the army to study, or hold him back?

Yussef says he’s not sure.

“No mission is easy. It was my life dream to study engineering and I had to do it,” he said. “The electricity situation, it’s a mess.”

Iraqi army Lt. Col. Abadi Mashkoor Sultan, commander of 1st Battalion, 56th Baghdad Brigade, left, talks to Lt. Col. Gregory McVay, security director for the 72nd Joint Area Support Group-Central, about security issues in the International Zone in Baghdad. The evening meeting took place on the 14th of July Bridge over the Tigris river. McVay meets Abadi, who commands all Iraqi army troops in the International Zone, regularly. (Michael Abrams/Stars and Stripes)

Amir: Looking for an escape

Seeing foreign forces in his country didn’t anger Amir; he saw only opportunity.

“When I saw first Chinooks in the sky, I had tears in my eyes,” Amir said. “They were tears of joy.”

But more than seven years after the U.S. invasion, and with two years served in the Iraqi army, Amir’s early hopes of living a normal life have been wiped away.

This is Amir’s modest dream: Working a 9-to-5 job, providing for his family, and seeing his wife at the end of each work day. He says it can’t happen for him in Iraq.

“There is not a lot of optimism within the army and there isn’t any true democracy in Iraq,” he said. “We feel like things are as they used to be. It’s going back to the old way.”

Amir believes there’s not much left worth fighting for in his country. Public figures serve for their own benefit, not the public, he said — and the military is not much better.

Seeing how well American soldiers are treated by their commanders, he wonders why it’s so much tougher in his army.

“If I do a 30-year career, maybe I’ll see my family for 10 of those years,” he said, explaining the long, mandatory separations and deployments required in the Iraqi army.

In 2008, Amir joined the army after failing to find regular work following his 2006 college graduation.

“Everybody is here for the money,” said Amir, who is engaged to be married.

By Iraqi standards, the money is good. The average annual salary for a soldier is about $7,000.

Yet Amir still feels like a prisoner. He’s hoping that the endemic corruption he so abhors will be his ticket to escape the 15 years of service he agreed to when he first joined.

He’s saving money, and one day hopes to bribe his way out of the army and get his family to America.

“As long as there is corruption,” he said, “I can get out of the military.”

Long way to go

In the eyes of many Iraqis, bad news abounds: massive unemployment, a headless government, a fragile peace threatened daily by car bombs, shootouts and assassinations.

For its part, the Iraqi army is still hobbled by bureaucracy.

The simplest of decisions — such as granting an interview request — must be approved at the highest levels.

“We need to refresh the army,” Yussef said. “What I’ve learned from the Americans is openness to discussion. Lower ranks can make contributions.”

However, Lt. Col. Abadi Mashkoor Sultan, who commands the 1st Battalion of the 56th Baghdad Brigade, says today’s noncommissioned officers are held in higher regard than in the old days.

“Soldiers are treated much better now,” said Abadi, who served in the old Iraqi army for six years in the early ’70s before fleeing the country.

Back then they got stale bread, he said; today, the food is fresh. Most troops endured brutal hardships. The abuse of Shiite conscript soldiers by their Sunni officers was commonplace.

Today, the Iraqi army is all-volunteer, but soldiers must make a 15-year commitment.

While the old army was more competent in some ways, the new army is quickly improving, Abadi said. The U.S. has trained and equipped 273,618 Iraqi troops. In early June, Abadi’s troops assumed full responsibility for securing the International Zone, the central area of Baghdad, formerly known as the Green Zone, that is home to the Iraqi government and numerous embassies. American forces had long been the face of security here, but now they’re nowhere to be seen.

Top U.S. commanders say the Iraqis are ready to assume control of their country. But Amir is much less certain.

“It’s difficult to tell right now. It’s all mixed up,” Amir said. “We won’t know for another 15 or 20 years what will happen.”

()