A flag-draped casket holding the remains of Army Pfc. Charles McAllister is unloaded from an Alaska Airlines honor flight at Seattle-Tacoma International Airport, Aug. 15, 2024. (Kevin McAllister)

More than a century after his combat death in France during World War I, Army Pfc. Charles McAllister will be buried Wednesday with full military honors at Acacia Memorial Park in Seattle.

The 25-year-old doughboy from Seattle went missing during the Aisne-Marne offensive in northern France on July 19, 1918, and was subsequently presumed to be killed in action.

For the past 20 years, his unidentified remains lay at the Department of Defense forensic laboratory in Hawaii until a DNA sample from a descendant led to his identification earlier this year.

The sample came from 91-year-old Gerald McAllister, according to Gerald’s son, Kevin McAllister.

That branch of the family had no knowledge of Charles McAllister, much less that he had gone missing during the war, Kevin McAllister said by phone Friday from the home he shares with his father in Lake Stevens, Wash.

“It wasn’t until I received a certified letter in the mail from the military, basically stating that they believed they found the remains of a long lost relative of ours in France,” he said.

Three male members of the family subsequently provided DNA samples, and they began earnestly researching their family tree to know more about their unknown relative.

“The first picture that we saw of him is a spitting image of my dad’s brother, Uncle Tommy,” he said. “They could be twins.”

It is unlikely the soldier’s remains would have been identified if not for work by Jay Silverstein, a former DOD forensic anthropologist who refused to give up on the case, and Beverly Dillon, a great niece from a different branch of the family.

In 2004, two sets of remains from an unmarked grave in France were transferred to the U.S. military’s forensic lab at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam. The lab at that time was operated by Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command, which has since morphed into the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency.

In 2005, Silverstein, a forensic anthropologist at the lab, successfully identified one set of remains as being those of Pvt. Francis Lupo, Silverstein told Stars and Stripes in 2020.

But the second set defied quick identification.

After Silverstein completed his analysis of those remains, a historian deemed the case “unsolvable,” Silverstein said at the time.

The case always nagged the anthropologist, though, and when the 100th anniversary of America’s entry into World War I arrived in 2017, he pulled the case out for another look.

He scoured the available clues such as uniform insignia, used geographic information system mapping to reconstruct battles and sought documents from the National Archives, including dental records.

Silverstein narrowed the possible identities to two missing soldiers, but his supervisors ordered him to drop the work because DPAA’s charter did not authorize work on WWI cases.

Silverstein’s relationship with the lab’s management was thorny, and he left the position in 2019.

But convinced the remains were Charles McAllister’s, Silverstein sought out the soldier’s descendants to get DNA verification.

Charles McAllister poses in his World War I uniform in this undated photo. (Beverly Dillon)

In the summer of 2019, he reached Dillon by phone at her home in a small Montana town near Glacier National Park.

As it turned out, the missing soldier was a subject of family lore for Dillon, who was then 80 years old.

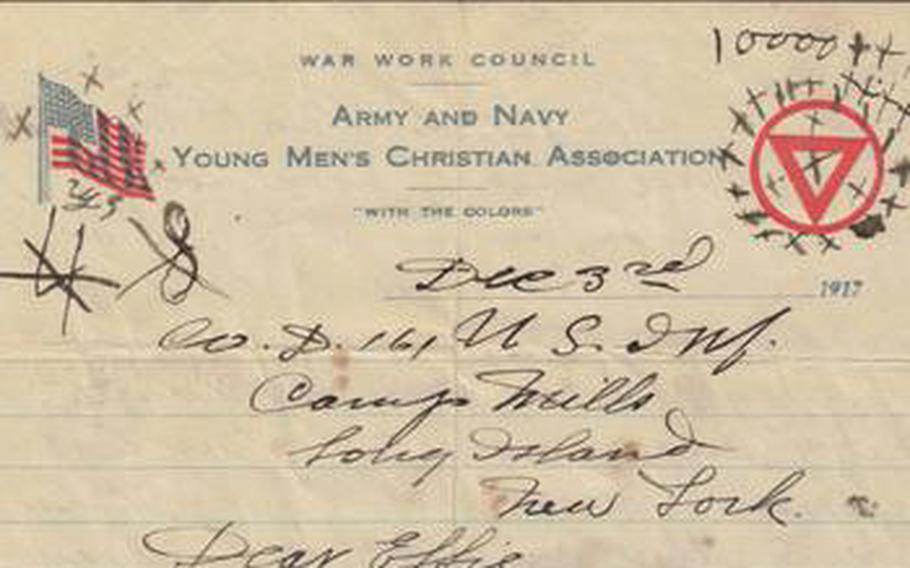

On her family room wall hangs a framed letter that her great uncle Charles sent to his sister Effie — Dillon’s grandmother — on Dec. 3, 1917, from New York before shipping out for France.

During the call, she read him the letter, which closed with the words: “From boy gone away to war, remember me in the sweet by and bye and I’ll come home when the war is over.”

“I always remember that first phone call I made to Bev after tracking her down through genealogical research,” Silverstein said in an email Saturday. “When she pulled the framed last letter of Charlie from the wall and read it to me, I had goosebumps and was almost in tears.”

The first page of a letter written by Charles McAllister to his sister Effie dated Dec. 3, 1917, sent before he shipped out from New York for France, where he died in July 1918, during the Second Battle of the Marne. (Beverly Dillon)

Dillon and her son submitted DNA samples to the Defense Department DNA Registry about a month later, but the case stalled out.

Dillon and Silverstein separately reached out to numerous members of Congress for help in pushing the case along.

DPAA Director Kelly McKeague outlined the agency’s position on the World War I case in a Nov. 23 letter to Sen. Maria Cantwell, D-Wash., in response to the lawmaker’s query, writing that the agency “is not authorized by statute to account for remains in conflicts before World War II.”

During an Aug. 6 phone interview, Dillon said she credits Rep. Ryan Zinke, R-Mont., with getting the case back on track after she wrote his office in 2023.

“Within 48 hours I was contacted by his aide in charge of military matters, and all the information I could give was passed to the Army Human Resources Command in Fort Knox,” Dillon said. “They and I poured through my ancestry again, and we both came up with one lineage tree that went through a male line for four generations.”

That line led to Gerald McAllister, whom the DOD regards as the dead soldier’s closest next of kin.

“This case would not have been solved without her help and determination as well as many unnamed volunteers who assisted me with genealogical work, archive retrieval, GIS analysis, and moral support,” said Silverstein, now a professor at Nottingham Trent University in England.

Still, he said he remains angered that it took five more years to ID McAllister after “his identity was incontrovertibly identified through multiple lines of forensic evidence.”

Dillon was in Seattle on Thursday when her great-great uncle’s flag-draped casket arrived via honor flight by Alaska Airlines.

That flag will be folded and handed to Gerald McAllister during the burial ceremony, but a second flag will be presented to Dillon, Kevin McAllister said.

“She’s worked harder on this than anybody, I believe,” he said. “I wanted them to make sure that she got a flag.”

Gerald McAllister, 91, salutes a plane at Seattle-Tacoma International Airport, Aug. 15, 2024, bringing home the remains of his great uncle, Pfc. Charles McAllister, who was killed during World War I and remained missing for more than a century. (Kevin McAllister)